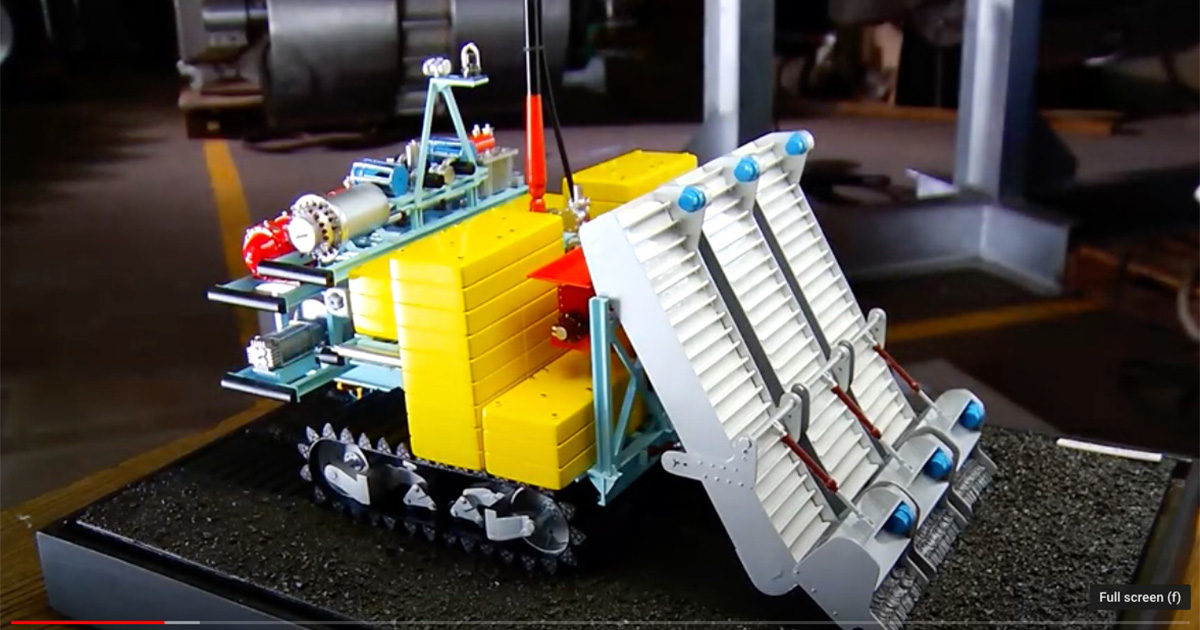

Varaha-1, a self-propelled seabed mining machine for the collection of polymetallic nodules. Photo: Ministry of Earth Sciences

Thiruvananthapuram: While India is readying to mine the seabed, some 6,000 meters below sea level, a senior official from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) says, “there is a need for a moratorium on deep-sea mining”.

In a statement shared with The Wire, Dr Bruno Oberle, the IUCN director general, says that the technical and economic viability of seabed mining remains controversial and the risks, known and widely documented, are not acceptable.

Citing scientific studies, Oberie adds that “impacts cannot be assessed, managed or compensated”.

Interestingly, even when the IUCN is calling for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, India is moving ahead swiftly to dig the seabed. In February, the Indian government uploaded a document online seeking public comments on the amending of the Offshore Areas Mineral (Development and Regulation) Act, 2002. The deadline for suggestions ended on March 11.

The Geographical Survey of India (GSI) claims that “some 79 million tonnes of heavy mineral resources and 1,53,996 million tonnes of lime mud” can be dug out from Indian waters. And it can take out some 745 million tonnes of construction sand from the territorial water.

Between March and April in 2021, India had sent Varaha, an underwater mining crawler named after the Hindu god Vishnu’s third incarnation, 5,270 metres deep into the Central Indian Ocean. It traversed 120 m on the seabed and mined a few potato-sized poly-metallic (manganese) nodules containing iron, nickel, copper, titanium and cobalt. Designed and operated by the Chennai-based National Institute of Ocean Technology (NIOT), Varaha was then conducting real-time tests.

Rs 4,000 crore budgeted

According to the Indian government, preliminary estimates indicate that 380 million metric tonnes (MMT) of polymetallic nodules comprising copper, nickel, cobalt and manganese are available within an allocated area of 75,000 sq km for exploration in the Central Indian Ocean basin. The estimated value of these metals is about Rs 9 lakh crore ($110 billion). The polymetallic sulphides are expected to contain rare earth minerals including gold and silver.

Following the tests, in June 2022, the Indian government also set up a special department under the Ministry of Earth and Sciences titled Deep Ocean Mission (DOM) and allotted it a little over Rs 4,000 crore for five years to move forward. And as part of speeding up the process, the Indian government has proposed competitive bidding to improve transparency in the allocation of mineral resources under the sea. The government says that the area under a production lease shall comprise contiguous standard blocks and shall not exceed an area of 15 minutes latitude by 15 minutes longitude. The lease period of blocks set now is for 50 years.

Plundering Kadalamma

Meanwhile, talking to The Wire, Father Eugene Pereira, vicar general, archdiocese of Thiruvananthapuram, and leader of fisherfolk in south Kerala, said that “this seabed digging is going to be a disaster for not only fisherfolk but for all”.

“This is all part of the blue economy plans. We have plundered land and space. Now, the greed is to plunder the seabed,” Fr Pereira said.

According to Fr Pereira, the digging and gauging of the ocean floor by machines can alter or destroy deep-sea habitats and will stir up fine sediments on the seafloor, creating plumes of suspended particles.

“I have read that these particles may disperse for hundreds of kilometres, take a long time to resettle on the seafloor, and affect ecosystems and commercially important or vulnerable species,” Fr Pereira added.

Meanwhile, Jack Mandalo Jonas Miranda, a Left union leader among fisherfolk in Thiruvananthapuram, raised his concern over potential leaks and spills of fuel and toxic products during the mining.

“Won’t this kill the fish?” he asked.

“The marine ecology is going to be disturbed. Plundering (Kadalamma) is not good,” he said adding that this will end in loss of their livelihood.

A study on deep-sea mining published in Frontiers in Marina Science says that most deep-sea ecosystems targeted for mining have some combination of ecological characteristics that make them particularly sensitive to anthropogenic disturbance, such as being largely pristine, highly structured, very diverse, dominated by rare species, and slow to recover.

The study sees dangers in both direct and indirect impacts of mineral extraction in the deep sea, saying it will result in a significant loss of biological diversity.

“Direct impacts may occur through the removal of target material and associated organisms within the mine site and include habitat loss, fragmentation, and modification through altered mineral and sediment composition, geomorphology, and biogeochemical processes,” the study reads.

And the indirect impacts, according to the study, on the seabed and water column both within and outside of the directly mined area, will be the smothering of habitat, interference with feeding activities, and the release and spread of nutrient-rich and toxin-laden water from the generation of plumes.

According to another study published in the same journal, the deep sea represents 95% of the global biosphere in terms of inhabitable volume.

The study adds that only a fraction of the deep sea has been scientifically studied and there are many valid concerns relating to seabed mining, one of which is the disturbance to as-yet-undescribed biota.

“In the past 20 years, for example, newly reported species range from invertebrates, such as a yeti crab, to large marine vertebrates including elusive beaked whales and some deep-sea species with long life spans are vulnerable to physical disturbance because of their slow growth rates,” the study adds.

Precautionary pause

Globally, Maoris, the indigenous people in New Zealand, the Alliance of Solwara Warriors in Papua New Guinea, and the Deep-Sea Mining Campaign (DSMC), a group of NGOs and citizens from the Pacific Islands, Australia, Canada and the US, concerned about the likely impacts of deep seabed mining on marine and coastal ecosystems and communities, are outraged.

India has a contract with the International Seabed Authority (ISA) for deep seabed mineral exploration. The ISA is a UN body set up to regulate the exploration and exploitation of marine-non-living resources of oceans in international waters.

The ISA has only issued exploration contracts but is developing regulations to govern the transition to exploitation. However, in June 2021, the Nauru government notified the ISA of their intention to start deep-sea mining, triggering a rush to finalise the ISA regulations.

The Nauru government and The Metals Company (TMC), a Canada-based mining start-up sponsored by Nauru, were trying to speed up the approval for a mining license. And Nauru has already undertaken exploration.

Germany and Costa Rica have joined the bandwagon of France, Spain, Chile, New Zealand and several Pacific nations in opposing deep sea-bed mining.

They are saying that they do not believe there is enough available data to evaluate the impact of mining on marine life and have called for a “precautionary pause” or a ban on mining in the high seas.

Rejimon Kuttappan is an independent journalist and the author of Undocumented, Penguin 2021.