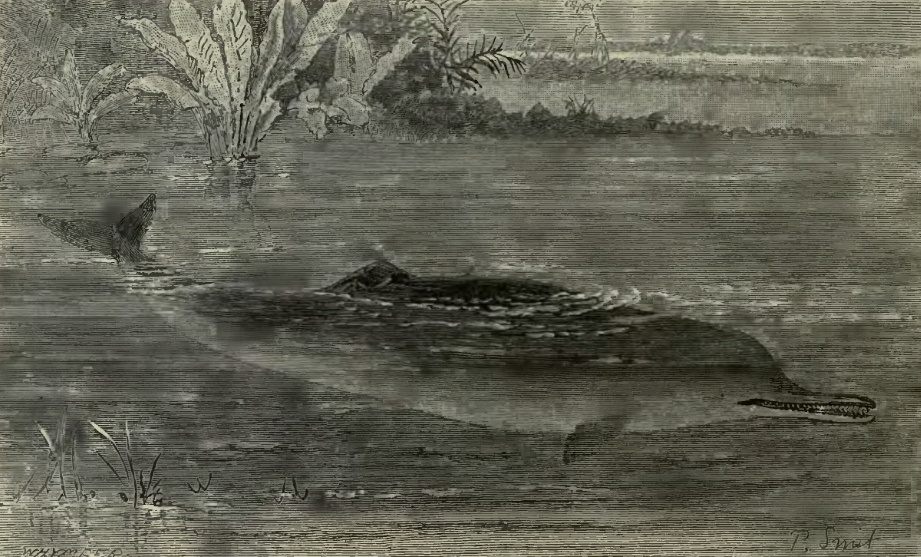

Quiet flows the Ganga as it snakes its way through Bihar, but under its surface, there is a symphony. Tiny mayflies let out shrill, pulsating calls. Catfish grunt, boom and drum. A series of steady, clicking sounds – like switches being flipped on and off – is a sign that the almost-blind Ganges river dolphin is nearby. These endangered mammals depend entirely on such high-frequency echolocating clicks to catch prey, communicate and move around in the river’s muddy depths.

However, noise from boat engines and propellers now frequently override this aquatic concert. Scientists have long suspected that they could be affecting the unique Ganges river dolphins as well. Now, a study published on October 28 leaves little room for doubt: these sounds are indeed drowning out the clicks and altering the dolphins’ behaviour.

Underwater noise from ships has been of growing concern in the open seas, where it interferes with the echolocation of animals that call at similar frequencies, such as dolphins and toothed whales. It disrupts disrupts foraging and communication.

Studies also show some species trying to alter their calls in order to be heard. For example, bottlenose dolphins near Florida increased the frequency of their whistles as underwater noise got louder.

But while marine mammals can often move away from such soundscapes, the Ganges river dolphin doesn’t have much wiggle room. This species is largely restricted to the Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers (and their large tributaries) in Nepal, India and Bangladesh. Indeed, the Ganga between Buxar and Manihari in Bihar has the highest population density of such dolphins in the world.

Then again, though a part of the Ganga is now protected as the Vikramshila Gangetic Dolphin Sanctuary, it’s also a national waterway with lots of vessel traffic. And the vessels’ propeller blades and underwater rakes produce high-frequency sounds that interfere with the dolphins’ clicks.

To ascertain this, a team including Mayukh Dey, a researcher at the National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bengaluru, studied various aspects of the river at four sites between Doriganj and Kahalgaon in Bihar and quantified vessel traffic and ambient underwater noise levels before and during vessel passage. They also recorded the river dolphins’ clicks using hydrophones.

What they found was startling. The more boats moved over the surface, the louder underwater noise got. The dolphins could only increase their echolocation activity to cope with the noise produced by four or five vessels plying over the surface every hour. They used 30-40% more clicks per second to communicate over this noise. Finally, they emitted louder clicks for a longer duration than in quiet conditions, according to Dey.

When 7-11 vessels passed by every hour, their noise completely drowned out the dolphins’ clicks. In response, when the water levels were low, the dolphins called to each other more softly and at an even higher frequency. This departs completely from their usual behaviour.

And when a lot of vessels passed by when the water level was low – a common sight in the summer – underwater noise was constantly high and the dolphins couldn’t keep up.

“Higher water levels not only provide more space for the dolphins to move about but also act as a buffer [that] dissipates noise underwater,” Dey explained.

Also read: Is the Endgame Inevitable for the Ganges River Dolphin in Assam’s Barak River?

One of the shallower and noisier sites the team surveyed was Doriganj, where 11 boats on average passed by in an hour. Dolphins would frequently leap out of the water and dive back head-first, slapping their tails in the water – an unequivocal sign of stress.

The scientists found that the energy cost, or metabolic stress, the animals incurred in shallow waters more than doubled when the noise breached the 100-110 dB mark.

“One compromise to live in such noisy conditions is to not call as often as they do,” Dey said.

Herein lies the problem.

“These dolphins depend almost completely on sound,” Dey continued. “So not calling could potentially affect the dolphins’ abilities to forage, navigate and communicate with one another.”

This is a cause for worry because a part of the Ganga is already a national waterway. The Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI) is further augmenting the river’s vessel-carrying capacity for the Jal Marg Vikas Project, at a cost of Rs 5,369.18 crore. Thankfully, it’s still possible to limit anthropogenic underwater noise and protect the Ganges river dolphin population.

One way, according to the study team, is to reduce traffic on the waterway and improve propeller technologies to produce less noise. Another is to maintain near-natural river depth by maintaining adequate flow from irrigation dams upstream and inflow from tributaries.

“We often don’t recognise underwater noise as a pollutant,” Jagdish Krishnaswamy, a researcher at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), Bengaluru, and a member of the team, told The Wire. “Maintaining ecological flows in the Ganga must take cognisance of underwater noise impact as well.”

The conclusions and advice are “at once scientifically defensible, constructive and practical,” said Randall Reeves, chair of the IUCN Species Survival Commission of the Cetacean Specialist Group and an independent scientist, in an email.

Also read: Modi’s Waterway Project in Varanasi May Only Do More Damage to the Ganga

Gill Braulik, a research fellow at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland who studies the closely-related Indus river dolphin, said the findings prove there are “clear limits to the amount of habitat disturbance the Ganges river dolphin can tolerate without there being serious impacts on the species”.

“Decision-makers in India, as well as anyone else who cares about preserving the country’s rich and diverse natural heritage, should give very serious consideration to this rigorous and timely study,” Reeves added.

Nachiket Kelkar, another researcher at ATREE, argues their study can help government agencies like the IWAI improve their plans for the river so they don’t trouble the Ganges river dolphin. According to sources, one such study is already underway.

Aathira Perinchery is a wildlife biologist-turned-journalist who writes about wildlife and conservation science in India.