The latest stories of the author can be read at…

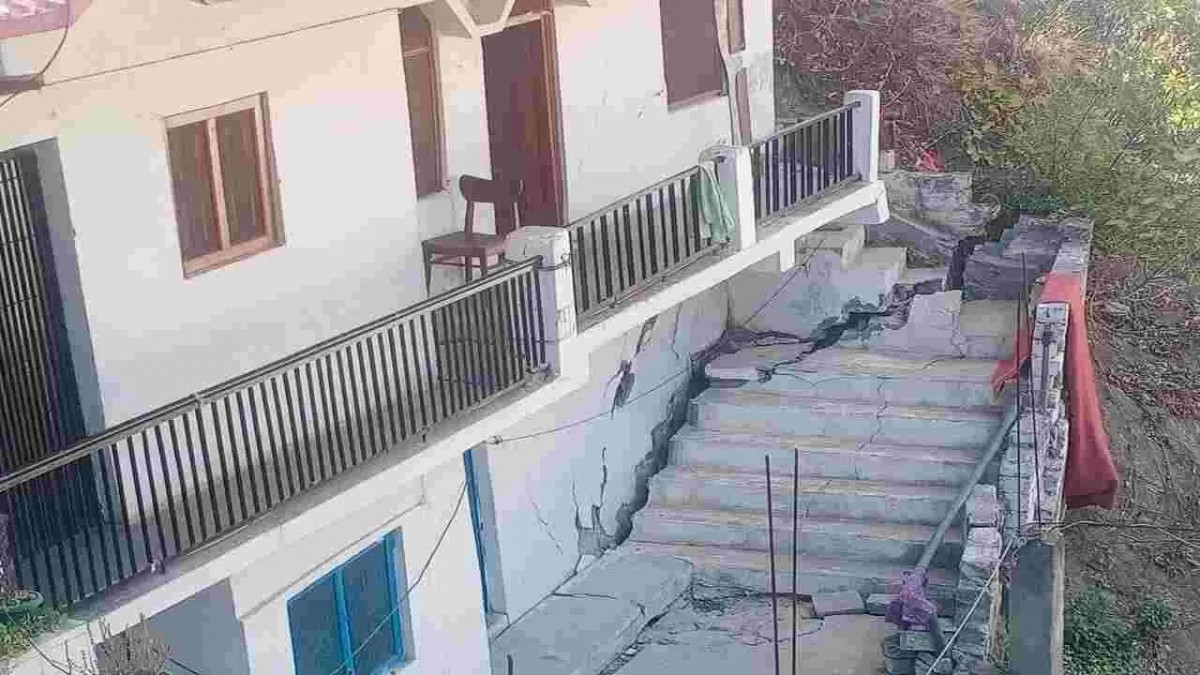

Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand have witnessed intense flooding and landslides over the past few weeks. Photo: Screengrab via Twitter

Kochi: Powerful brown rivers of moving mud peppered with fallen tree trunks, snaking on streets beside houses. Hillsides, some carrying with them homes, collapsing into valleys, onto roads, over cars. Thousands of houses damaged, thousands of people evacuated. Crops, livestock, livelihoods – all lost.

Over a two-week span of heavy showers in July, more than 100 people lost their lives in north India; more than 80 of these deaths occurred in Himachal Pradesh, one of the worst-hit states. August has again brought heavy rainfall in the hill states of Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. The death toll has mounted to over 70 in Himachal and on August 18, the state government declared it a “state calamity”. On Monday, four people died in a landslide in Uttarakhand’s Tehri district.

The disasters unfolding in the hill states are a result of unplanned development on unstable mountains that are already facing extreme weather events, scientists and environmentalists said. Without planned, resilience-friendly development and adaptation measures such as district-level micro plans to deal with the changing climate, there may be no respite for the people or the environment in these regions.

Beas River #Himachal #HimachalPradesh #Mandi #thunag #Heavyrains #Rain #Rainfall #HeavyRain #Heavyrainfall #Heavyflood #Himachal #HimachalNews #flood #floods #flooding #Exclusive #BreakingNews #BREAKING pic.twitter.com/szHY70t25N

— Vikas Bailwal (@VikasBailwal4) July 9, 2023

More rains to come

The monsoon has brought the hill states of Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand very heavy rains. Since August 13, more than 70 people have died in Himachal Pradesh. Shimla has been particularly badly hit, and 21 lost their lives in three major landslides in the area. Per one report, Himachal has encountered 113 landslides over 55 days into the monsoon this year, according to the state’s disaster management department. Per another, 227 people have died in the state (and 38 are missing), and 12,000 houses have been damaged since the onset of the monsoon on June 24 this year. On August 18, the state government declared it a “state calamity”. Damages to people and property due to the rains this season since July have resulted in losses of Rs 10,000 crore, chief minister Sukhvinder Singh Sukhu said.

And more rain is on the cards. On August 22, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) predicted heavy to very heavy rainfall over parts of north India including Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh over the next three-four days. Per PTI, the IMD in Shimla has issued a red alert in eight of its 12 districts for August 22. The department has also issued an orange alert warning of “heavy to very heavy rains” on Wednesday and Thursday and a yellow warning of heavy rain for the next two days.

Experts have said that the heavy rains here are part of a phenomenon called “break-monsoon” conditions.

“This is a typical pattern during the monsoon season every year. During this time, the axis of the monsoon trough shifts northwards and stays stationed over the Himalayas triggering heavy to very heavy rains over the hilly region,” said Mahesh Palawat, vice president (Meteorology and Climate Change), Skymet Weather, in a press release.

Climate scientist Roxy Mathew Koll said that monsoon rainfall patterns over India have seen a climatic shift in recent decades. Koll, a senior scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, Pune, said that the most significant change is that instead of having moderate rains spread out through the monsoon season, we now have intermittent long dry periods with short spells of heavy rains. This causes floods and droughts in the same season and occasionally in the same region or different parts of India, Koll said in a press release.

“We saw this pattern manifesting during the current year also. Even though the all-India average rainfall is near normal, the regional rainfall during the season has had deficits and floods.”

Heavy rainfall events can be a huge concern in these mountainous areas because some of the immediate impacts are flash floods and landslides. Almost 15% of the world’s rainfall-induced landslides occur in the Indian Himalaya; per one estimate, rainfall triggered 477 out of the 580 landslides that occurred in the Indian Himalaya between 2004 to 2017. For example, one study found that the June 2013 extreme rainfall event in Kedarnath in Uttarakhand triggered more than 3,400 new landslides in the area.

Links to a warming world

While the verdict is not out on whether the ongoing rains in Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand were made more likely by climate change (no attribution studies have analysed this specific event yet), research suggests that the world’s mountains are vulnerable to extreme precipitation events due to a warming world.

In their recent study, a team from the US’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory analysed whether the excess precipitation in mountain regions due to climate change occurs in the form of snowfall or rainfall. They found that rain will replace snowfall in mountain regions in the northern hemisphere.

“Our findings revealed a linear relationship between the level of warming and the increase in extreme rainfall: For instance, 1 degree of warming causes 15% more rain, while 3 degrees leads to a 45% increase in rainfall,” the lead author of the study Mohammed Ombadi said, in a news article by the Berkeley Lab.

The team also found that some mountain ranges are at greater risk of such extreme rainfall events than others are. The Himalaya is one of them. Others include the North American Pacific mountain ranges and other high-latitude regions. The impacts of such rain events both on the mountain ranges as well as downstream of them, are many, the scientists warn: floods, landslides and soil erosion.

“One quarter of the global population lives in or downstream from mountainous regions,” the news article quoted Ombadi as saying. “They are going to be directly affected by this risk.”

Commenting on the recent rains in Himachal Pradesh, Palawat said that a warming atmosphere has increased the intensity of rain tremendously.

“More warming means more energy in the environment, leading to more rain. Moisture availability is abundant in the atmosphere, which causes incidents like torrential rainfall in a short period causing damage like what we saw in Himachal and Uttarakhand this season.”

Unstable lands, unchecked construction

The fragility of the Himalaya, particularly that of the Shivaliks – the youngest of the Himalayan ranges in geological time – adds to these impacts of climate change. The Shivalik range is the youngest and most fragile part of the Himalayas as they are made up of debris, said Y.P. Sundriyal, Head of the Department of Geology, HNB Garhwal University, Srinagar, Uttarakhand, in a press release. Rocks here are made up of sandstone and shale rock, which is the weakest form of any rock, and they cannot withstand heavy rains because they are composed of clay minerals, he said.

“The increasing torrential rainfall, deforestation, and unchecked construction have increased the chances of erosion. As humans, we have been challenging these mountains’ capacity for many years now. Increasing anthropogenic stress will only lead to disaster,” he commented.

Unplanned construction and deforestation have contributed greatly to the natural disasters that these hilly tracts have been witnessing of late, experts agree. Earlier this year, buildings and the ground in the hill town of Joshimath in Uttarakhand developed cracks. Residents blamed the excavation work being undertaken as part of the construction of the Tapovan Vishnugad hydel power project as one cause of land subsidence in the area. Researchers have said that the construction of the Char Dham project – an ambitious 900 km-long all-weather road through the state to promote religious tourism – also played a role in land sinking or subsidence in the area. Moreover, the town of Joshimath was located where it should not have been, as per a 1976 report: on an ancient landslide. More cracks have appeared in the vicinity over the last couple of months as well, including on national highways.

These hill tracts – part of the Himalaya, which is one of the most seismically active continental regions – are set to witness more construction. In May this year, the Himachal Pradesh government invited bids for 27 hydropower projects in the state. As Joshimath in Uttarakhand’s Chamoli district still grapples with cracks, residents of Dharchula town in the neighbouring district of Pithoragarh took to the streets in February this year to protest against the proposed Bokang-Baling Hydroelectric Project in the Darma Valley. The tunnelling and excavation for the dam, they fear, will cause irreparable damage to their town and property.

Rampant unsafe construction along fragile hill slopes has made hill states like Himachal Pradesh highly vulnerable to extreme rainfall, earthquakes and landslides, Aromar Revi, director of the Indian Institute for Human Settlements and IPCC coordinating lead author, told The Wire. “The same places also experience serious water scarcity in the dry months, because water that should have percolated into the soil and subsurface aquifers has run off during the monsoon, causing havoc downstream in plains cities like Delhi.”

Uncontrolled expansion of poorly planned, designed and executed buildings along with drastic changes in land use and tree cover, has increased uncontrolled runoff, blocked natural drainage, destabilised vulnerable slopes, reduced the flow of springs and made flash flooding and landslides more common, said Revi.

“More extreme rainfall and precipitation that comes with climate change will only make things worse.”

The kind of development in Himachal Pradesh has shifted over the past two decades, said Manshi Asher, co-founder of Himdhara Collective, a Himachal-based NGO that has been working on issues of environmental justice and land and forest rights in the Lahaul, Spiti, Kinnaur, Chamba and Sirmaur regions.

Post the 1990s, the liberalisation of the power sector witnessed private players coming into the power production industry, Asher said. After the Kyoto protocol and talk of sustainable development, run-of-the-river projects – which, it was claimed, displaced fewer people and needed less land – were preferred over larger reservoir dams. These projects stored and diverted rivers though large scale excavations, tunnelling and surface constructions for its dams; new roads and widening of existing ones for better access to these dams; the installation of transmission lines to transfer electricity to other states. In the process a lot of forests were destroyed, she said. In Himachal, rapid deforestation and land use change especially in the last decade or so has caused slope destabilisation. The extent to which this has altered local climatic conditions, and the area’s hydrology and geology, has hardly been assessed, Asher commented.

Deforestation and high tourist footfalls

A 2007 study based on satellite imagery predicted that at the current rate of deforestation, total forest cover in the Indian Himalaya will decrease from 84.9% (of the area under forest cover in 1970) in 2000 to 52.8% in 2100. Only about 10% of the land area of the Indian Himalaya will be covered by dense forest [forests that have a canopy cover of more than 40%] by 2100. When this happens, it could wipe out a quarter of the region’s endemic species. The study predicts that the Western Himalaya – in Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand – will suffer higher losses in both total and dense forest cover when compared to the Eastern Himalaya. It also pointed out how government data from the Indian Agricultural Statistics Summary, however, was contradictory: it suggested that forest cover will increase by around 40% by 2100. Such “inaccurate reporting of forest cover” can underestimate the impacts of deforestation, they noted.

At present, news of deforestation continues to pour in. As recently as around two months ago, the high court of Himachal Pradesh took up a suo moto Public Interest Litigation to look into allegations of illegal deforestation in Mandi district’s Nachan forest division, per a report by Himbu Mail. The Court has constituted a committee to provide a detailed report by October 10.

The massive urbanisation and increased construction for tourism-related projects have increased tourist footfall too, Asher said.

“Tourist footfall which was previously concentrated in Dharamshala and Shimla has now spilt over into other valleys,” Asher said.

Put together, all these changes have affected the ecology, environment, and put high demands on resources. Plastic and solid waste – which were not as much of an issue before – is now a major concern, especially in tourist centres, said Asher.

However, authorities are downplaying the role of such extractive human activities in disasters by ascribing them to just climate change, according to Asher.

“It has become a thing to hide behind for the government – that local action is not possible because it will be solved at a national or at a global level because it is a global problem,” said Asher. “Global problems also require global solutions but what we are getting are solutions like net zero [through] hydropower because it is renewable. So in the name of climate change mitigation, we are actually exacerbating the existing ecological and environmental threats in the region. This is the irony of the whole situation.”

Planting trees or greening is being pushed as a false solution and is creating more problems, she added. The carbon-centric climate change narrative is a concern and does not take into account its ecological footprints and social costs, Asher said.

Sukhvinder Singh Sukhu

Towards more decentralised governance

In order that environmental crises or disasters aren’t triggered, we need preventive policies and regulatory frameworks, according to Asher. “But what the government is actually doing is loosening the regulatory framework. For instance, by saying that the consent of the gram sabha is not required for a project. Or that there’s going to be easier environment clearance,” commented Asher.

It’s already happening. For instance, projects pertaining to “national security” or “defence” in forest land within 100 km of India’s borders will no longer require clearance under the Forest Conservation Act (1980). Earlier this month, the union government amended the Act to make this change, and several others. Experts have raised serious concerns but the amendment was cleared in Parliament without resistance: it will soon be law.

The entire governance structure has to change, Asher commented: it has to be decentralised, has to empower the community more, and has to become more democratic.

“Adaptation is something that people are doing,” she told The Wire. “When climate changes, they do try and change cropping patterns. People, especially vulnerable communities, need support to adapt. Instead of supporting them the government is actually hampering their livelihoods. There need to be more concerted efforts to work with the communities in a participatory and democratic way to arrive at a localised solutions. But that requires a lot of dialogue. At the district level, if land use planning involves the grama sabhas and panchayats, then things can change.”

Koll too highlighted the importance of focusing action at the local level.

“The pace of global warming is now accelerated, and we need urgent action as these extreme conditions will intensify in the near future,” he said in a release. “Climate action and adaptation at local (panchayat) levels should go parallel with mitigation at global and national levels. I am concerned that there is less focus on local adaptation. Instead of waiting for weather forecasts yearly, we need to disaster-proof locally, based on sub-district wise assessment,” said Koll.

Micro-action plans at the district level would be crucial, Koll added. “As of now, we are responding to these events when they happen or when there’s a forecast,” he told The Wire. “These [extreme rainfall] events are to intensify further – which means we should not wait for forecasts, we should address them at the policy level.”

According to Revi, the economic development model of the hill states has to be re-examined in the context of climate change.

“Protecting and conserving ecosystems like hill forests that provide safe and clean water, limit flooding and landslides, and provide renewable hydropower and valuable services that others, typically in the plains, should consider ‘paying’ for. Multi-hazard-prone zones have already been identified in most hill states. Stringent enforcement of planning and building regulation, sustainable road-building practices and relocation only in the rarest of rare cases when all other options have failed are strategies that have been successful in the past. They need to be backed by investments and the ability to implement at scale.”