The sense of smell is used by animals and even plants to identify hundreds of different substances that float in the air. But compared to that of other animals, the human sense of smell is far less developed and certainly not used to carry out daily activities. For this reason, humans aren’t particularly aware of the richness of information that can be transmitted through the air, and can be perceived by a highly sensitive olfactory system. AI may be about to change that.

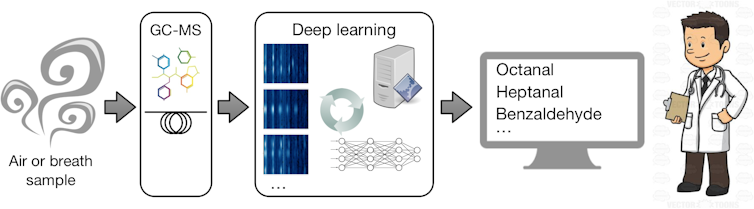

For a few decades, laboratories around the world have been able to use machines to detect very small amounts of substances in the air. Those machines, called gas-chromatography mass-spectrometers or GC-MS, can analyse the air to discover thousands of different molecules known as volatile organic compounds.

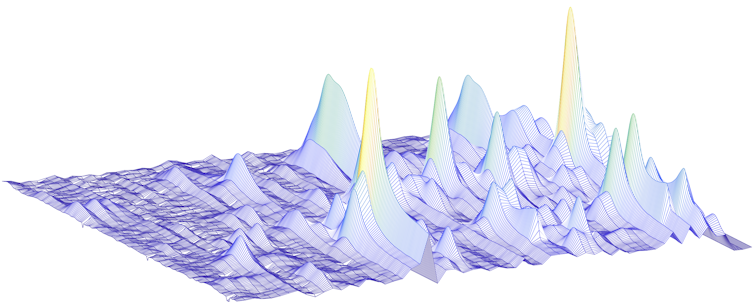

In the GC-MS machine, each compound in a sample of air is first separated and then smashed up into fragments, creating a distinctive fingerprint from which compounds can be recognised. The image below is a visualisation of a small part of the data from an analysis of a breath sample.

Each peak represents a fragment of a molecule. The particular patterns of such peaks reveal the presence of distinct substances. Often even the smallest peak can be crucial. Among the several hundred compounds present in the human breath, a few of them might reveal the presence of various cancers, even at early stages. Laboratories around the world are therefore experimenting with GC-MS as a non-invasive diagnostic tool to identify many illnesses, painlessly and in a timely manner.

Unfortunately, the process can be very time consuming. Large amounts of data need to be manually inspected and analysed by experts. The sheer amount of compounds and the complexity of the data mean that even experts take a long time to analyse a single sample. Humans are also prone to error, can miss a compound or mistake one compound for another.

How artificial intelligence can help

As part of Loughborough University’s data science team, my colleagues and I are adapting the latest artificial intelligence technology to perceive and learn a different type of data: the chemical compounds in breath samples. Mathematical models inspired by the brain, called deep learning networks, were specifically engineered to “read” the traces left by odours.

A team of doctors, nurses, radiographers and medical physicists at the Edinburgh Cancer Centre collected breath samples from participants undergoing cancer treatment. The samples were then analysed by two teams of chemists and computer scientists.

Once a number of compounds were identified manually by the chemists, fast computers were given the data to train deep learning networks. The computation was accelerated by special devices, called GPUs, that can process multiple different pieces of information at the same time. The deep learning networks learned more and more from each breath sample until they could recognise specific patterns that revealed specific compounds in the breath.

In this first study, the focus was on recognising a group of chemicals, called aldehydes, that are often associated with fragrances but also human stress conditions and illnesses.

Computers equipped with this technology only take minutes to autonomously analyse a breath sample that previously took hours by a human expert. Effectively, AI is making the whole process cheaper – but above all it is making it more reliable. Even more interestingly, this intelligent software acquires knowledge and improves over time as it analyses more samples. As a result, the method is not restricted to any particular substance. Using this technique, deep learning systems can be trained to detect small amounts of volatile compounds with potentially wide applications in medicine, forensics, environmental analysis and others.

![]() If an AI system can detect markers of disease, then it becomes possible to also diagnose whether we are ill or not. This has a great potential, but it could also prove controversial. We simply suggest that AI could be used as a tool to detect substances in the air. It doesn’t necessarily have to diagnose or make a decision. The final conclusions and decisions are left to us.

If an AI system can detect markers of disease, then it becomes possible to also diagnose whether we are ill or not. This has a great potential, but it could also prove controversial. We simply suggest that AI could be used as a tool to detect substances in the air. It doesn’t necessarily have to diagnose or make a decision. The final conclusions and decisions are left to us.

Andrea Soltoggio, Lecturer, Loughborough University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.