Following the publication of this article, Dr Rajiv Garg, the director-general of health services in the Union health ministry issued a notice dated July 20 asking people to refrain from using valved N95 respirators.

Bengaluru: Arnab Bhattacharya likes to joke that he is a mask-crusader. Two months ago, while the COVID-19 outbreak was spreading across India, his lab began testing the quality of N95 respirators – a kind of mask that protects wearers against airborne droplets containing the novel coronavirus.

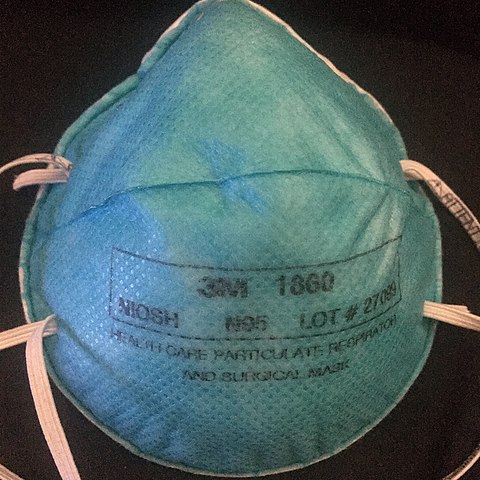

Bhattacharya is a physicist at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai. His work with masks began when COVID-19’s onset triggered a major shortage of N95 respirators from established manufacturers, such as the American firm 3M and Mumbai’s Magnum Health & Safety. This forced the Tata Memorial Centre, a major cancer hospital in Mumbai, to consider using masks from new manufacturers they weren’t familiar with. So the hospital asked Bhattacharya for help ensuring these respirators worked as their manufacturers claimed.

That is, they wanted to know if the respirators filtered 95% of particles larger than 0.3 microns[footnote]1 micron is a millionth of a metre[/footnote], as N95 masks are meant to.

Since most readymade mask-testers, by companies like TSI Incorporated, cost several lakhs and aren’t easily available, Bhattacharya’s team jury-rigged one using an air-pollution monitor. They then tested their device on masks from established N95 manufacturers, like Magnum, and found the results to be reliable.

But when the team began testing other purported N95 masks, they were surprised. Some of the masks were “nowhere close to N95,” Bhattacharya said.

These poor-quality masks filtered only some 60-80% of 0.3-micron particles, putting healthcare workers at risk of infection. Intrigued, Bhattacharya began scouring online marketplaces for more N95 masks. He found many of them were indulging in false advertising.

For example, masks that were only effective against particles larger than 3 microns – which would work against bacteria but not virus aerosols — were labelled N95. Other N95 respirators claimed to be washable. Bhattacharya said this is unlikely because most such masks use electrostatic charge to trap small particles.

“You will kill it if you wash it, because it will lose the charge,” he said.

Still others claimed to be certified by agencies that don’t certify masks.

“I am appalled at the number of fake N95 masks,” Bhattacharya said.

Once he realised the extent of quality issues, he conducted multiple webinars to help both healthcare workers and non-experts understand them. But the problem of shoddy masks is not restricted to Tata Memorial Centre, or even Mumbai.

COVID-19 has triggered a surge in demand for N95 respirators. Subsequently, many manufacturers with little experience in making these products have stepped in – but few of them are producing effective masks.

“Almost 150 manufacturers have come up in the past three months. Some of them are basically counterfeiting brands,” Sanjeev Relhan, chairman of the Preventive Wear Manufacturers Association of India, told The Wire Science.

While there is little data on sales for N95 masks in India, which were low before COVID-19, the outbreak prompted public-sector firm HLL Lifecare to issue a tender for 6 lakh masks in March 2020 for government use alone.

Fake masks can endanger lives, so Relhan and other experts say it is crucial to do two things: rein in errant manufacturers and bolster the supply of genuine masks.

To do the first, according to Relhan, the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) must act against makers of faulty masks. Since April 2020, when India passed the Medical Devices (Amendment) Rules, all medical masks have been under the CDSCO’s purview. Manufacturers do have 18 months to transition before they comply with the Rules, but if the CDSCO wishes, it could shorten this period and invoke the Rules sooner, Relhan said.

Once CDSCO does this, it can require manufacturers to comply with the requisite quality standards for masks, such as IS:9473, developed by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS), according Anil Jauhri, an expert in quality certification systems. He previously headed India’s National Accreditation Board for Certification Bodies. “There is nothing stopping them,” he said.

But when The Wire Science asked the Drug Controller General of India, V.G. Somani, who heads CDSCO, whether the organisation plans to act against defaulting manufacturers, he didn’t respond.

Still, simply regulating the manufacture of N95 respirators won’t solve the problem. To comply with standards like the IS:9473, manufacturers need access to laboratories in which they can routinely test their products. But given the low demand for N95 masks until the COVID-19 outbreak, few manufacturers invested in such facilities, Jauhri said.

Even now, he argued, in-house labs may not be feasible for many small manufacturers. To tackle this problem, both Relhan and Jauhri are calling for either the Union health ministry or the BIS to set up labs able to test N95 masks.

“For N95 masks, there are currently no external labs, outside manufacturers’ facilities, to test for quality. It’s a big problem,” Jauhri said. By setting up such labs and allowing small manufacturers to access them, he added, India can kickstart the emerging respirator industry.

Why does quality matter?

There are many ways in which an N95 mask can fail. For instance, under IS:9473 and a similar American standard, called 42 CFR 84, an N95 mask must have a particulate filtration efficiency of 95%; must be breathable, which means when a wearer inhales air through the fabric, the air pressure mustn’t drop dramatically; must form a tight seal around a person’s face so that unfiltered air doesn’t leak inside; and must resist fire and withstand temperature fluctuations without losing its efficacy.

Only when these – and several other features listed in the standards – are met without exception can the mask block aerosols, like those that transport the novel coronavirus.

Across the world, several national agencies, including the BIS, certify masks that meet these standards. Of these, only the US National Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) uses the term N95. So strictly speaking, only a NIOSH-certified mask can claim to be an N95, although the term has become a catchall for all similar masks. So even though BIS and the UK’s INSPEC certify so-called FFP2 masks, which are broadly equivalent to NIOSH’s N95, people often refer to FFP2 masks as N95.

Other comparable devices are the KN95, meeting Chinese standards; P2, meeting Australian standards, and D2, meeting Japan’s.

When the COVID-19 outbreak began in India, given the demand for effective N95 masks, two government agencies other than BIS also began testing them: the South Indian Textile Research Agency (SITRA), Coimbatore, and a facility of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) in Gwalior. But these two agencies offered only one-time testing, to help manufacturers refine their prototypes. And neither is a certifying agency.

Further, even the one-time tests are limited. Both agencies test only three of the many parameters under IS:9473, namely particulate filtration efficiency, breathability and flammability. They don’t test for many others, including leakage.

However, many Indian companies who got their masks tested by SITRA and DRDO are claiming to be certified today, TIFR’s Bhattacharya said. These misleading claims have become so rampant that both DRDO and SITRA have warned manufacturers to stop. But the companies continue to dupe healthcare workers into buying inadequately tested masks by using SITRA and DRDO logos.

Testing versus certification

Sometime in April, the Punjab state government began procuring N95 masks from a Ludhiana-based company called Shiva Texfabs Ltd. The company had only made yarns and knitting fabric until then, and was manufacturing N95 masks for the first time. One of the hospitals that received Shiva Texfabs’ masks was the Ludhiana Civil Hospital, which was treating COVID-19 patients.

Almost immediately, several of the hospital’s doctors realised the products were substandard. The masks had ear loops instead of head bands, so the fit wasn’t tight enough. They were also made of a flimsy material, a hospital employee who didn’t wish to be named told The Wire Science.

But things really came to a head when three of the hospital’s workers tested positive for COVID-19. “There was a hue and cry. Things just burst open. Staff nurses and junior doctors were crying,” the employee recalled. Convinced that the bad masks had led to the infections, doctors and nurses began a protest on May 19. Eventually, Ludhiana’s civil surgeon Rajesh Bagga stepped in and assured the workers that the masks would be replaced.

One thing that went wrong in the Civil Hospital episode was that government doctors were misled by the company’s claims. Bagga told The Wire Science that Shiva TexFabs’ masks had claimed certification by both SITRA and DRDO. Even today, Shiva TexFabs’ website continues to claim that its N95 masks are certified by DRDO, although it makes no mention of SITRA.

But according to the BIS website, Shiva Texfabs has only applied for certification, and its first sample failed tests. An email sent to an ID listed on the company’s website went unanswered.

Many companies are exploiting the difference between certification and testing, although certification is a more involved process, Relhan said. For example, when BIS certifies a mask, it doesn’t just require a manufacturer to test the mask once under IS:9473, but also requires that the manufacturer have a quality control system in place to test every new batch of masks.

Such controls are necessary because small changes on the manufacturing line can result in an ineffective mask, several manufacturers told The Wire Science. Even the fabric used to make the mask can vary from batch to batch, they said.

Rakesh Bhagat, director of Magnum Medicare, which makes both NIOSH- and BIS-certified masks, gave the example of seams on the fabric of N95 masks, which are sealed using ultrasonic waves. “If you don’t maintain the same frequency of the ultrasonic waves, you can puncture the fabric, and the mask can lose its filtration efficiency,” he said.

Misleading guidelines

Given the confusion, the Union health ministry hasn’t exactly cleared the air. In March, the ministry released guidelines for the use of COVID-19 PPE. But these guidelines are at odds with those of some other national health agencies. The ministry’s guidelines call for N95 masks with exhalation valves, which are typically used in settings like coal-mines, because they allow exhaled air to be removed and keep the wearer comfortable.

However, in hospitals, where the mask is also supposed to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 from the healthcare workers to patients, these are a bad idea. “An exhalation valve is a big no,” Bhattacharya said. “It provides a zero-resistance path for exhaled air, so that all sneezes, coughs, etc. will go directly out without any filtration.”

This is why the US Centres of Disease Control recommends against masks with exhalation valves in hospitals, especially during surgeries, when a sterile environment is important. But the Indian health ministry’s guidelines have led to government procurement agencies like HLL Lifecare issuing tenders for N95 respirators with valves.

The health ministry also hasn’t clarified on the use of ear loops to fasten masks. NIOSH doesn’t allow manufacturers to install ear loops on masks for healthcare workers because typically they can’t be tightened. Only adjustable head straps are allowed. “When you use ear loops, the seal around the face is not perfect. Ninety percent of the time, such masks fail fit-tests. Then there is air leakage,” said Bhagat of Magnum Medicare. But many Indian manufacturers continue to make masks with ear loops.

Hundreds of fake certificates

With few checks and balances to ensure quality in the respirators industry, shoddy masks continue to trickle into Bhattacharya’s lab – many accompanied by fake certificates.

In June, Bhattacharya received two masks labelled ‘EcoPanda 95’ that had been supplied by a Bangalore-based company to Tata Memorial Centre. One had an exhalation valve and the other didn’t. When Bhattacharya evaluated them on his tester, the valved mask only filtered 60% of small particles, and the valve-less one filtered 68%.

“These are the worst masks I have seen in the past two months,” Bhattacharya said.

When he cut up the mask with a pair of scissors, he saw why the EcoPanda masks were so porous. Instead of using heat or ultrasonic waves to seal the seams, the manufacturer had stitched them, leaving holes that let air through. What’s more, the mask was made of only two fabric layers, while typical N95 masks have up to five.

When The Wire Science contacted Vishal Pipada, the director of the company that had supplied the EcoPanda masks, he said the masks hadn’t been made by his firm but were from Global Air Filter India Pvt. Ltd., another firm in Bangalore. Pipada also shared five certificates for Global Air Filter’s masks, including one from the “Food & Drug Administration”. But The Wire Science found that at least four of these certificates were fake: they were issued by agencies that are not allowed to certify.

For example, in one of the certificates, a company called UK Certification and Inspection Ltd claimed to certify Global Air Filter’s mask according to EN 149:2001, the European respirator standard. However, only bodies notified by the European Commission can certify European standards, and UK Certification isn’t one of them.

On another certificate Pipada shared, an agency called “QCS” had awarded a “Food & Drug Administration” certification to Global Air Filter. Jauhri, who recently wrote a document on how to spot fake certificates, said the US Food and Drug Administration doesn’t allow any external agencies to certify products under its name.

Fake certificates have become a booming cottage industry, and hospitals are having a hard time spotting them, experts say. Relhan cited the example of a government hospital in North India whose tender for N95 masks elicited the interest of 122 firms offering a range of certificates. “Can you believe it? Out of 122 certificates, 120 were fake,” he said.

There are no quick solutions to this problem, experts say – but CDSCO must start chipping in by acting against offending manufacturers. Relhan suggested it might also be a good idea for a body like the Quality Council of India to host a website where mask-users could check the authenticity of certificates.

The most important factor is greater awareness among users. There is complete confusion right now, Bhattacharya said, about what an N95 mask is and its specifications. And this he added won’t do because in India, which today crossed 1 million COVID-19 cases, people will need to continue using masks.

“The way things are going, masks are here to stay.”

Priyanka Pulla is a science writer.

The reporting for this article was supported by a grant from the Thakur Family Foundation. The foundation did not exercise any editorial control over the contents of the article.