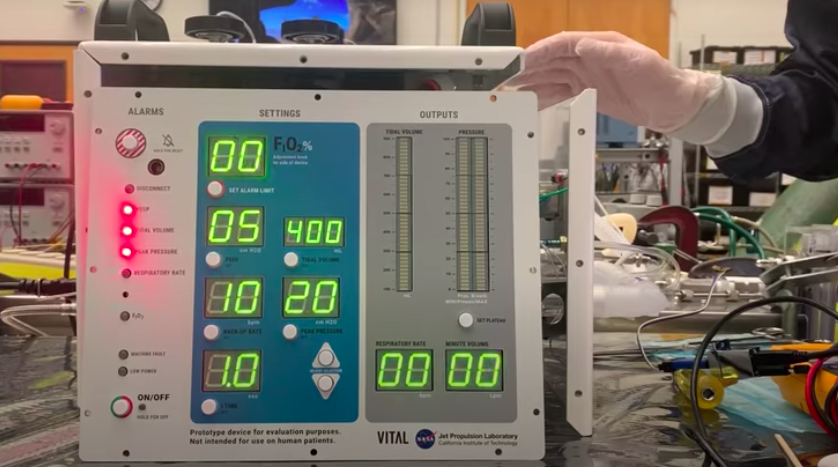

Featured image: A ventilator built by NASA. Photo: NASA.

As Italy took over from China in March earlier this year as the principal fount of new COVID-19 cases, European governments scurried to meet the spike in demand for ventilators. Army technicians were pressed to the task, companies attempted to quadruple production and whole countries scrambled to get their hands on devices.

The situation in India was quite encouraging at that point, with just 114 cases. However, researchers around the country weren’t becoming complacent: they knew ventilators were critical and that India would soon need more. They began to collaborate, and news reports of their initiative and progress did the rounds in April and May.

But come June, and India’s COVID-19 case load was increasing by nearly 10,000 every day, and the country’s healthcare infrastructure had been pushed to its limits. This seemed like a good time to support hospitals and COVID-19 care centres with indigenously developed low-cost ventilators.

Where were they?

As it happens, the scientists and engineers building ventilators have different levels of clarity among themselves about which conditions their devices have to meet and what they have to do to get their devices to the market. As a result, while some groups have entered the manufacturing phase, others are stuck with testing and paperwork. And even among devices ready to be marketed, specifications and capabilities vary.

A professor at one IIT said on condition of anonymity that his team was “still improving on the prototype” and had sought “medical inputs, collaborators and also certification from medical organisations” before they could start manufacturing. When asked about the certificates required to make their device market-ready, the professor said they were “still looking for answers to these questions”.

This correspondent encountered different versions of this particular reply at other research institutes as well. The science of ventilators is well-understood but there seems to be little clarity on what exactly makers need to do to get their ventilators to the market.

A second professor at a different institute said their prototype had tested well, and that they had shared a few units and demonstrations with some hospitals in major cities. The professor also said they had tied up with a major PSU to manufacture them. However, he didn’t have answers to questions about the standards to which their prototype conforms (and about the PSU’s production capacity).

Many teams had had limited exposure to medical requirements and came up with prototypes after consulting local hospitals and their staff. The sophistication of each prototype in effect became an outcome of the expertise available to consult, plus product design capabilities among team members. As a result, different groups have been making ventilators with different use-cases.

A third professor at a third institute was more upbeat than others. Their prototype had entered the early manufacturing phase after the medical institution they were working with provided an ‘ethical approval’ for clinical validation. The team had tested their prototype using lung simulators and ventilator testers, and ensured their device complied with IEC 60601 standards.

The IEC 60601-2-12 standard in particular pertains to the performance of critical care ventilators and is mandatory to market a relevant product in North America and Europe. It covers the safety and performance of medical electrical equipment.

However, the upbeat professor acknowledged the “lack of accepted specifications and standards for testing and verifying these new kinds of low-cost ventilators”.

A standard, according to him, would make it “easier for multiple parties within the country to make such devices and validate [them] to ensure sufficient quality and patient safety standards are met.” He said such standards were important preconditions to scaling up innovative solutions.

Also read: COVID-19 Ventilators Are Important – but They’re Not Perfect

Indeed, meeting standards is key to accepting any device for medical use. Without standards, it’s hard to know what differentiates a good ventilator from bad. And without domestic standards, it’s hard to know if benchmarks developed in other countries based on the clinical presentation of patients and healthcare infrastructure there are adequate here.

There has been a spate of reports of low-cost ventilators already in the field not being usable, compromising patient care as well as draining public resources. For example, to quote from a report by The Wire on May 21:

“Over the last few weeks, a harsh spotlight has been turned on hundreds of ‘Made in India’ ventilators that were supplied free of cost to Ahmedabad civil hospital by Jyoti CNC Automation Ltd, whose chairman-cum-managing director, Parakramsinh Jadeja, is seen in the state as being close to chief minister Vijay Rupani. … The machines, according to [Ahmedabad Mirror], were strongly endorsed by Rupani, who claimed this cheap ventilator was designed and produced in 10 days. Rupani’s enthusiasm, however, has not been backed by Gujarat’s government doctors.”

European governments had specified their requirements as well as worked with existing manufacturers to increase production quickly. On the other hand, the lead to develop low-cost ventilators in India came from a sense of ‘national duty’ at a time of crisis. While this is heartening, the enthusiasm still needed to be channeled through common protocols and targets.

A document published on March 31 on the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare website, under ‘Resources for Hospitals’, listed six “essential technical Features for ventilators for COVID-19”. A technical committee of the Defence Research and Development Organisation drafted it, and the list contains no reference to any Indian or international standard that a device should comply with.

As it happens, on June 19, the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) published a standard designated IS17426:2020, “developed as an interim arrangement, as an emergency temporary measure in larger public interest”. Entitled ‘ICU Ventilators for Use in COVID-19 – Specification’, the standard is based on essential features that Hindustan Lifecare Ltd., the PSU responsible for procuring PPE, has been using since mid-April.

Questions to BIS and members of the pertinent committees on why the standard wasn’t developed earlier went unanswered.

Additionally, Hindustan Lifecare Ltd. has amended its ‘Essential Technical Features’ documents at least three times. This document specifies the features of the ventilators it plans to procure. As a result, many innovators have reported being caught between changing expectations and product improvements, even as speed is of the essence. The total number of these features now stands at nine. Questions about the provenance of the three additional features went unanswered as well.

Ameya Paleja is a molecular biologist based in Hyderabad and blogs at Coffee Table Science.