People wait to receive a dose of Covishield at a hospital in Noida, August 30, 2021. Photo: Reuters/Adnan Abidi

- The Government of India has declared that it will vaccinate its entire adult population by December 31, 2021. But only four states are on track to meet this goal.

- A group of experts have proposed a simple action model, requiring states to use evidence available from serosurveys and with a local ‘sentinel surveillance’ programme.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected all aspects of human life around the world. It has caused considerable morbidity and mortality in every part of the human-inhabited planet, evolving into a widespread pandemic of exceptional magnitude – the only one to affect such a large swathe of the world’s population since the Spanish flu in the early 20th century.

According to the WHO, the global tally of cases, as of September 23, was more than 229 million. The number of deaths has already crossed 4.7 million worldwide. India has been no exception vis-à-vis the sheer number of cases and lives claimed by the disease. As of the same date, the virus had infected more than 33.5 million Indians. And as several seroprevalence surveys found, the actual number of persons infected could be much higher. The number of reported deaths in India due to the disease has also crossed an astonishing 0.4 million.

There are two major measures to halt the disease: vaccination and non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs); the latter includes effective containment and mitigation strategies and COVID-appropriate behaviour. Vaccination is a more sustainable method, as NPIs are often associated with severe economic downturns that disproportionately affect the lives and livelihoods of the underprivileged population.

India’s vaccination programme

India, a traditional mass-production hub for other vaccines, has been one of the largest manufacturers of COVID-19 vaccines as well. It has been one of the largest vaccine administrators globally. India also successfully developed its own indigenous vaccine, although its approval by the WHO and other countries is still pending.

However, the large population and the variable distribution of vaccines across different states, each with a different capacity to execute a mass-vaccination programme, have proved great challenges in the way of India’s vaccine coverage ambitions. This article aims to chronicle the journey of the Indian vaccination programme up to its current situation and illustrate the road that lies ahead to inform policy.

***

India began administering COVID-19 vaccines on January 16, 2021, in a drive that went on to become the world’s largest of its kind. The government has used the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, Covishield, manufactured by Serum Institute of India, Pune, and Covaxin, developed jointly by Bharat Biotech and the Indian Council of Medical Research, as the drive’s two mainstays. It also approved a third vaccine for emergency-use later: Sputnik V. Among recipients, 88% have received Covishield, 11% Covaxin, and only 1% Sputnik V.

India has from the start taken a more advanced coordination approach, through an online platform called CoWIN, developed and used extensively, and almost exclusively, to register every vaccinee. On the acquiring and supplying fronts, India couldn’t solely rely on COVAX, the WHO initiative to give low- and middle-income countries more bargaining power at the table with vaccine manufacturers. So India resorted to mass-producing Covishield and Covaxin.

After developing a universal platform and realising indigenous manufacturing, India’s vaccination programme took off with the Centre’s guidance and support. In the first phase, the Centre supplied states with vaccines purchased from the manufacturers. The health systems of individual states rolled out the vaccination operations – the “jab in the arm” component of the drive. This phase commenced on January 16, 2021, and inoculated healthcare and frontline workers.

The second phase focused on inoculating everybody over the age of 60 and people aged 45-60 with one or more qualifying comorbidities. From April 1, the Centre extended eligibility to all those older than 45 years, with or without comorbidities, and also launched a ‘tika utsav’, or ‘vaccination festival’, to encourage inoculation.

By this time, the Union government had also changed vaccine procurement norms, allowing state governments and private hospitals to procure vaccines directly from manufacturers. However, as vaccine deficits kicked in, several states announced that they would have to delay vaccine rollouts to those aged 18-45 years – the third phase, which the Centre had said could begin from May 1. Priorities about whom to vaccinate also shifted in many states depending on the availability of vaccines.

Since the latest phase commenced on June 21, vaccination coverage and pace of administration have picked up. Daily vaccinations are higher than ever before, while a previously reported gender gap also began to narrow.

Programme progress

As of September 23, India has administered over 846 million doses, including first and second, of the then approved vaccines. But almost eight months into the vaccination drive and the expanded initiative to include all those older than 18 years, this only translates to 21% of India’s population being fully vaccinated, and 64% being partly vaccinated. The devastating second outbreak of COVID-19 and the emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants have taught us that the country needs to accelerate the pace of vaccination.

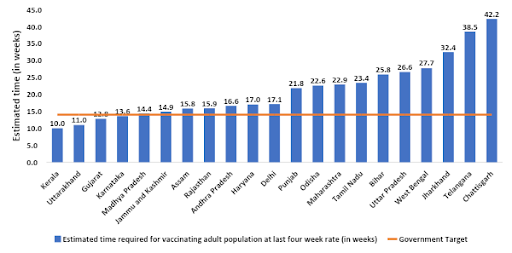

India has set a target to vaccinate its entire adult population by December 31, 2021, but at the current rate of progress – almost 52.6 million doses a week – India will need another 21 weeks to reach this target.

State-wise status

India is one of the world’s largest and most diverse countries. With its strong foundation of cooperative federalism, it has banked on its states to vaccinate its citizens. However, the pace of this programme has varied significantly across states due to the size of and the age-wise distribution of the population and due to the adoption of different strategies. The supply of vaccines to states has also been non-uniform. The rest of this article considers 21 states and UTs; we have excluded smaller states because they can achieve high coverage even with a small number of vaccinations.

Kerala had the highest first dose coverage (91.3%), followed by Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat, all above 80%. The states with lower first dose coverage were Jharkhand, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, all three below 60%. As for second dose coverage: Kerala again stood first (39%), followed by Uttarakhand and Gujarat, both above 35%. Uttar Pradesh and Bihar had the lowest second-dose coverage.

Kerala had also administered the highest number of doses per 1,000 people of the 60+ age group, followed by Jammu and Kashmir and Gujarat. That is, much of the most vulnerable demographic had been covered to a great extent in these states, most with multiple doses as well. Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Jharkhand had administered the fewest doses per 1,000 people of the 60+ age group.

The Government of India has declared that it will vaccinate its entire adult population by December 31, 2021. But only four states are on track to meet this goal. Chhattisgarh, Telangana and Jharkhand almost certainly won’t be able to achieve 100% coverage of their adult populations by this date.

More importantly, vaccine supply is yet to match demand in many states.

Way forward

Our analysis indicates that it is feasible to generate and compile data to enable evidence-based prioritisation of actions planned at the local level. We propose a simple model to implement evidence-based action. It requires all states to use the available evidence from local seroprevalence surveys and institutionalise a ‘sentinel surveillance’ programme for COVID-19 using the existing hospital framework. This programme can gather good-quality evidence of infections, severe disease and mortality due to COVID-19.

For planning purposes, an ideal unit of operations would be the district. Officials should already know vaccination coverage data at the sub-district levels. So each district can draw up an action plan specific to primary healthcare centres (PHCs), as shown in the 2 x 2 contingency table below, using both serosurvey and coverage data.

PHC-wise or sub-district-wise data can be designated ‘low’ and ‘high’, and coverage in the area can be designated ‘low’ and ‘high’ (on either side of the national median values, for example). Areas that have low vaccination coverage and low seroprevalence should be prioritised for vaccination.

These areas (red cell) will have the highest number of cases and deaths whenever the next wave occurs here.

The areas in yellow are to be surveilled, and whose pace of vaccinations will have to be ramped up.

The areas with high vaccination coverage and seroprevalence can gradually open schools and ease other activities, while monitoring the relevant indicators.

If officials and experts can collect and analyse robust data on hospitalised people (e.g. if their infection can be traced to the relevant community or context of infection), they can add this information as well to the decision-making process.

Recommendations

For the Centre:

- Ensure adequate vaccine supply to states with a relatively lower population and low coverage

- Improve healthcare facilities in states with low coverage of 60+ population, including Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Jharkhand and Bihar

- Amend policy to include every citizen of the country who is currently outside the vaccination ‘radar’

For states:

- Improve vaccine administration rate in currently low-performing states like Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Jharkhand, Bihar and Chhattisgarh

- Implement NPIs in states with lower second-dose coverage (even if first-dose coverage is high), like Madhya Pradesh and Assam (while continuing to ensure universal masking in public places)

- Emphasise mass-media and community health-education campaigns and engage local influencers to increase awareness on the importance of vaccination and reduce vaccine hesitancy, if any

- Recruit more vaccinators and train them better while widening the vaccine administration network

Soham Chakraborty is a senior research assistant, Nishisipa Panda is a research consultant and Ambarish Dutta is additional professor – all at the Indian Institute of Public Health, Bhubaneswar.

Giridhara R. Babu is professor and head – life course epidemiology, Indian Institute of Public Health, Bengaluru.

Ranjana Singh is associate professor, Indian Institute of Public Health, Delhi.

Gina N. Sharma is at the Office of the President and Senior Manager – External Communications and Digital Media, and Surabhi Pandey is a research scientist and adjunct faculty member – both at the Public Health Foundation of India.