India’s Drug Controller General Dr V.G. Somani, 2019. Source: YouTube

Mumbai: The COVID-19 antiviral drug that the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and Dr Reddy’s Laboratories developed together, 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-DG), received emergency use approval from the Drug Controller General of India (DCGI) on May 1.

Several experts have already contested the ‘evidence’ on which the drug was approved, as well as the opacity of and methodological flaws in the underlying clinical trials. In fact, the results of the phase 2 and 3 trials conducted with 2-DG still haven’t been published as a preprint or a peer-reviewed paper. The only information on these trials is available from a government press release and the trials’ registrations on the Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI), here and here.

In the last few days, Dr Reddy’s has conducted a series of virtual seminars on 2-DG – all hosted on ‘Doc Vidya‘, the company’s portal to “enhance” doctors’ “medical knowledge”.

Promoting a new drug is tough. Companies need to spend considerable sums of money to market it but can’t undertake direct end-user advertisement. Instead, they bank on proxies like medical representatives, commission paid articles, etc. And with the webinars on ‘Doc Vidya’, it seems Dr Reddy’s may have found a new channel – one in which to market the drug as well as reveal more about it than was already apparent.

The webinars provided a glimpse of the hazy results from the 2-DG clinical trials.

Several experts to whom The Wire Science reached out reacted with disdain to the quality of evidence on display. (One of them, Dr Varun Cheruparambath, an interventional cardiologist at Medical Trust Hospital, Cochin, had flagged the webinar and its contents on Twitter earlier.)

The evidence so far

The Wire Science had earlier explained how 2-DG’s approval was based on evidence that wasn’t there. A short recap follows.

Preclinical data – DRDO first presented some data to suggest 2-DG may inhibit the growth of the novel coronavirus in groups of cells cultured in the laboratory, with no indication that 2-DG would have the same effect in humans, a vastly more sophisticated collection of cells.

Clinical data – Both phase 2 and phase 3 trials for 2-DG had a common flawed design. They measured patients’ outcomes on a subjective scale (such as scoring some aspects of their improvement on a scale of 1-10 scale). The common advice when using such subjective endpoints is to blind the trial: to ensure the doctors administering the trial don’t know who received the treatment (2-DG) and whom the placebo. However, neither trial had such blinding either.

As a result the results are deemed at the outset to be much less reliable than is typically expected from human clinical trials involving vaccines.

In addition, we already know several drugs – ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, doxycycline, azithromycin and lopinavir – inhibited virus growth in the lab but failed human clinical trials. This rendered the need for, and the absence of, a good clinical trial more problematic.

Also read: Lack of Definitive COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Is Leading To Chaotic Medicine

Dr Reddy’s webinar

One of Dr Reddy’s webinars on 2-DG was held on May 30, 2021. It’s available to view on the Doc Vidya website here.

The session was divided into four parts:

1. Dr Anant Narayan Bhat, of the DRDO, made a presentation on the preclinical data

2. Dr Reddy’s head of medical affairs, Dr Sagar Munjal, summarised the clinical trials

3. Dr Praveen Chandra, a cardiologist at Medanta hospital, Gurugram, described his experience with 2-DG

4. A panel discussion

Dr Munjal’s presentation was of particular interest. A month after the DCGI’s approval for 2-DG, he shared major bits of information from the trials. At the time, according to a counter installed on the ‘Doc Vidya’ website, 25,000 people were watching the session.

(Note that ‘Doc Vidya’ also said “its contents are for the use of registered medical practitioners only”.)

‘New’ phase 2 results

One of the requirements of a good trial is a pre-specified endpoint. Say you want to test a drug against COVID-19 in hospitalised patients. After administering the drug, you can measure different parameters – say, SpO2 level, the number of days until an RT-PCR test is negative, the breathing rate and the mortality.

Let’s assume that your drug does not work. It failed to show any improvement on the parameters you had selected. However, you discover by accident that the drug decreases the viral load.

However, you hadn’t pre-specified lower viral load as one of the trial’s endpoints. If you are scrupulous, you will admit that the trial failed on its endpoints. But if you are unscrupulous, you may claim your drug reduces the viral load and hide the fact that it doesn’t improve the endpoints you designed/intended it to work on.

In research parlance, doing the latter is called “hypothesising after the results are known” – or HARKing. Dr Cheruparambath told The Wire Science that declaring the endpoints after the results are known is considered unethical and introduces significant bias to a trial.

To prevent this, researchers need to register their primary endpoint, the main parameter that decides whether the drug works, and the secondary endpoints, which are for additional analysis, on the CTRI before the trial begins.

The primary endpoint for 2-DG’s phase 2 trial was the time required for patients to score 4 or lower on a 10-point scale to characterise the patient’s clinical status. In his presentation, Dr Munjal showed a slide entitled “Baseline Demographics”. Here, the median score for patients enrolled in the phase 2 trial was 4 – the cut-off score of the primary endpoint.

As such, this makes the trial’s primary endpoint redundant.

Dr Munjal didn’t comment on this. An email sent to him hadn’t elicited a reply at the time of publishing this article.

The Subject Expert Committee (SEC), the group of independent experts that appraise evidence and guide India’s drug regulator of India, have also declined to approve several drugs that failed on the primary endpoint of their respective COVID-19 trials (although it also approved favipiravir, which, by the company’s own admission, had failed on its primary endpoint).

Also read: In India, Drugs for COVID Are Being Tested, Approved in Ways That Should Worry Us

Dr Munjal also presents “key data points” pertaining to some results from the phase 2 trial. The first is entitled “Time to achieve and maintain SpO2 >93%”. The median time is 2.5 days for participants that received 2-DG and 5 days for participants that didn’t. This difference was statistically significant, which is jargon for “the change seen is unlikely to be by chance”.

First, these results are from a trial with 44 patients – which is considered a small cohort. Second, “time to achieve and maintain SpO2 >93%” isn’t the primary endpoint of this trial nor one of the 15 secondary endpoints. But Dr Munjal doesn’t explain why he discusses this finding.

“The median score of the phase 2 trial patients is shown as 4 – which means ‘hospitalised but not on oxygen’, hence their stated result of median time till SpO2 > 93% is already going to be heavily biased as most patients (at least 50%) were not on oxygen to begin with,” Dr Cheruparambath said.

Next, he presented results from two of the 15 secondary endpoints that are statistically significant: “time to vital sign normalisation” and “time to discharge from isolation ward”.

The government press release, which followed the announcement of 2-DG’s approval, said the difference in “time to vital sign normalisation” was 2.5 days, whereas Dr Munjal said it was 3 days. This isn’t a trivial deviation: since the trial included only 44 patients, small differences can change the result from statistically significant to non-significant.

The third secondary endpoint Dr Munjal presented was “time to negative RT-PCR”. He explained that the p-value for this endpoint was 0.07 – a number that says the finding was not significant. However, he continued, his “crude analysis” showed the results were statistically significant. He does not explain what form the “crude analysis” took.

Overall, of the 15 secondary endpoints, Dr Munjal talked only about three because, he said, they “stood out”; he didn’t mention the other 12. We don’t know whether the drug failed on these endpoints.

(While 15 secondary endpoints may seem like a lot, Dr Manya Prasad, assistant professor of clinical research and epidemiology at the Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, New Delhi, said phase 2 trials could have multiple endpoints to detect a signal.)

Also read: Serum Institute Fracas Exposes Loose Ends of India’s Clinical Trial Machinery

Phase 3 results

In the CTRI entry for 2-DG’s phase 3 clinical trial, Dr Reddy’s doesn’t mention the primary and secondary endpoints. This is a big problem because we don’t know how many parameters they measured and on which ones 2-DG failed.

In his presentation on the phase 3 trial, Dr Munjal shared a slide with eight “key” endpoints. He said the first is the primary endpoint and that the rest are secondary. The succeeding slide has two more parameters – the safety endpoints.

There are several issues here. First, like the phase 2 trial, the phase 3 trial also uses subjective endpoints without blinding.

Second, Dr Munjal’s slide indicated that the WHO used the same 10-point scale in its famous SOLIDARITY trial that Dr Reddy’s used in 2-DG’s phase 3 trial. This is not correct. There is no mention of such a scale in either the research paper or the protocol published by WHO’s SOLIDARITY team. In fact, the SOLIDARITY trial relied on objective endpoints, like mortality after 28 days.

Next, Dr Munjal said that these were “pre-specified endpoints”. But since they were not shared on CTRI, we don’t know where they were pre-specified – or, in fact, if the trial team picked them after the trial had concluded.

Dr Prasad said that the possibility of selective outcome reporting needs a closer look.

Dr Munjal said that on the third day, 42% of patients in the treatment arm had a score of 4 on 10, compared to 31% in the control arm. This government press statement also specified this. However, this is a secondary endpoint. Dr Munjal didn’t say if the difference was statistically significant.

Similarly, Dr Munjal said that 12% in the 2-DG arm and 7% in the control met the primary endpoint threshold – a score improvement of 2 on the 10 point scale. Again, he didn’t say if the difference was statistically significant.

And like in the phase 2 trial’s presentation, Dr Munjal skipped sharing the results of the other secondary endpoints.

He also said trial sites had been overwhelmed because of the second wave in India and the results from the phase 3 trial should thus be considered to be a “preliminary interim analysis” and that he would share the data from additional analysis in a few weeks. This means, among many things, that clinical decisions during the trial weren’t uniform and objective but depended on the trial site’s capacity.

Dr Praveen Chandra

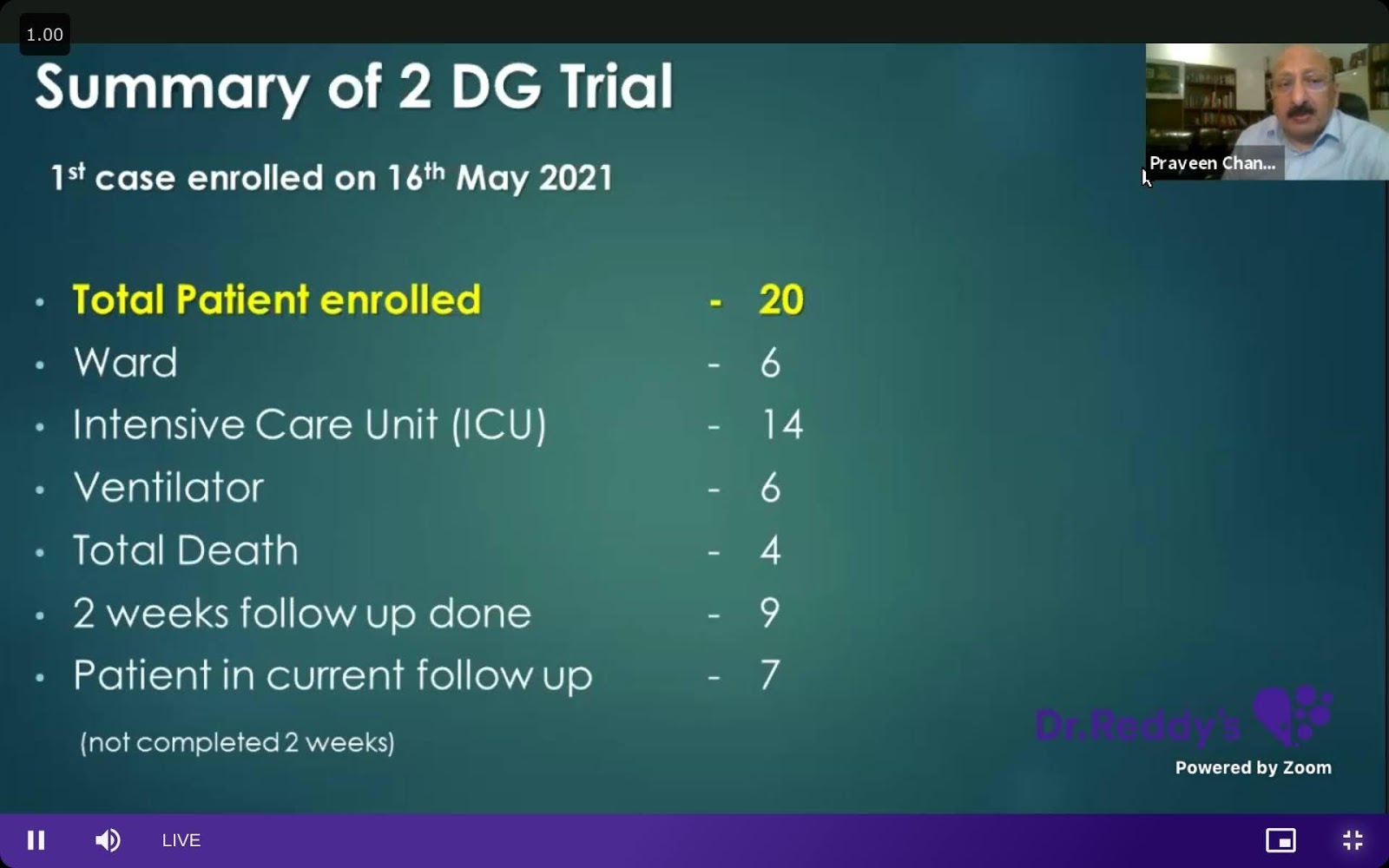

Dr Praveen Chandra’s presentation followed Dr Munjal’s summary.

During his presentation, Dr Chandra kept saying that he “enrolled” patients, but The Wire Science couldn’t find any CTRI registration for this trial. Dr Chandra also hadn’t replied to an email raising this and other issues at the time of publishing.

Dr Chandra also kept emphasising a surge of SpO2 among his patients after taking 2-DG. However, he didn’t explain how he was able to conclude that the surge was because of 2-DG – as he had no control group to compare with. Also, by his own admission, all his patients were getting steroids, which help increase SpO2 levels.

Dr Chandra and other experts on the panel also didn’t disclose if they had any conflicts of interest and/or if they had been compensated by Dr Reddy’s for their efforts.

The lack of such disclosure along with several misleading claims about 2-DG is concerning.

Also read: Have You Tested Positive For COVID-19? This is What Happens Next.

§

2-DG’s approval was the latest in a series of DCGI decisions founded on flimsy or no evidence. And following in the tracks of favipiravir, itolizumab and Virafin, 2-DG also still doesn’t feature in the Union health ministry’s clinical guidance document, prepared by experts at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences and the Indian Council for Medical Research.

“The lack of robust evidence and any potential harms are issues that deserve adequate consideration and unequivocal expression while recommending drugs for COVID-19,” Dr Prasad said.

The cost for 2-DG is reportedly Rs 990 per sachet; there appears to be some confusion if a sachet’s contents will weigh 2.34 grams or 5.85 grams. According to Dr Munjal’s presentation, a patient will have to be given two doses of 2.34 grams each a day for 10 days. The company didn’t respond to a request to clarify what costs a single patient might incur in the course of their treatment.

“The rushed approval in the absence of complete efficacy and safety should be a huge matter of concern,” Dr Cheruparambath said. “It may put patients at risk and add to the already-high cost of treatment rather than actually benefiting them in any way.”

The Wire Science hasn’t yet received a reply to a questionnaire sent to Dr Reddy’s. This article will be updated as and when it responds.

Ronak Borana is a science communicator based in Mumbai. He tweets at @ronaklmno.