Health is a human right. And yet, the sad reality is that, 40 years after the Alma Ata declaration pledging “Health For All,” half the world is still without access to essential health-care services.

To address the global health-care crisis, all countries must commit to the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, which include Universal Health Coverage. This involves financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.

In a path-breaking development, 40 years after publishing the first Essential Medicines List, the World Health Organization (WHO) this week published the first Essential Diagnostics List.

This new list will greatly enhance the impact of the Essential Medicines List (EML). After all, essential medicines require essential diagnostics.

While everyone accepts the importance of essential medicines and vaccines, there is little acknowledgement of the central importance of diagnosis — the first, critical step in the management of all diseases.

Addressing the diagnostic gap

Imagine treating tuberculosis (TB) without a diagnosis, or managing diabetes without access to lab testing. It is stunning that in 2018, nearly 40% of the estimated TB cases are either not diagnosed or not reported. An estimated 46% of adults with Type 2 diabetes worldwide are undiagnosed. Millions of episodes of acute fevers are managed by health-care providers without any diagnosis.

How can we deliver quality primary health care, if we can’t even diagnose common and priority conditions? And how can we detect and control outbreaks, if we don’t know what we are dealing with?

This week, WHO took a huge step in addressing this diagnostic gap, by publishing its first Essential Diagnostics List (EDL), a list of the tests needed to diagnose the most common conditions as well as a number of global priority diseases.

Essential diagnostics are defined as diagnostics that satisfy the priority health-care needs of the population and are selected with due regard to disease prevalence and public health relevance, evidence of efficacy and accuracy and comparative cost effectiveness.

What does the first EDL include?

The first EDL, compiled by a WHO expert advisory group on in-vitro diagnostics, contains 113 tests.

Of these, 58 are basic tests (e.g. haemoglobin, blood glucose, complete blood count, urine dipstick) intended for detection and diagnosis of a wide range of common communicable and non-communicable conditions.

These basic lab tests form the basis for an essential package of tests at the level of primary care and higher. The remaining 55 tests are designed for the detection, diagnosis and monitoring of “priority” infections — namely HIV, TB, malaria, hepatitis B and C, human papillomavirus (HPV) and syphilis.

All tests included in the EDL are backed by existing WHO evidence-based guidelines. The list is presented in two tiers: Primary health care and health care facilities with clinical laboratories.

WHO will update the EDL on a regular basis, just as the EML is kept updated. WHO has plans to expand the list significantly over the next few years, and to include tests for antimicrobial resistance, emerging infections, neglected tropical diseases and additional noncommunicable diseases.

Implementing for impact

There are at least 10 potential benefits to an EDL: These include improving patient care, helping detect outbreaks, increasing affordability of tests, reducing out-of-pocket expenses for tests, reducing antibiotic abuse, improving regulation and quality of diagnostic tests, strengthening accreditation and quality of laboratories, improving supply chain and guiding the R&D of new diagnostic tools.

While the WHO EDL is a welcome development, the list, by itself, will not have an impact. To see a meaningful impact, countries will need to adopt and adapt the WHO list, and develop their own national lists.

Once national EDLs are in place, then mechanisms can be put in place to improve the availability, affordability and quality of included tests.

India, for example, has already begun the process to develop a national EDL. Hopefully, other countries will follow suit and find ways to realize the potential of an EDL in their settings.

Time to invest in laboratories

In addition to developing national EDLs, countries must invest in strengthening their laboratory networks. Currently, laboratory capacity is weak in many low-income countries, because of four key barriers: Insufficient human resources, inadequate education and training, inadequate infrastructure and insufficient quality, standards and accreditation.

Why have countries under-invested in laboratories? For too long, the global health community systematically promoted empirical or syndromic treatment for many conditions in low-income settings, because building a reasonable laboratory infrastructure was considered too difficult and expensive.

This explains the emphasis on “essential medicines” for more than 40 years, and the lack of an essential diagnostics list until now.

And then came the push in the 1990s to develop, implement and create a market around simple rapid tests (driven by malaria and HIV, mostly), as laboratory infrastructure was still scarce. However, the excessive focus on rapid, point-of-care tests (that still continues) further pushed back serious investments in laboratory strengthening.

Improvement of laboratories and strengthening health systems is still considered too expensive and difficult by most governments and donors. This explains why we struggle to manage conditions for which no good rapid tests exist. This also explains why health systems with weak laboratory infrastructure cannot detect outbreaks early, nor offer comprehensive diagnostic services that cover a wider range of conditions, including antimicrobial resistance and non-communicable diseases.

It is time to reject the mindset that rapid tests and syndromic treatments are “enough for poor countries,” and work towards ensuring that all countries have a functional, tiered, quality-assured laboratory infrastructure.

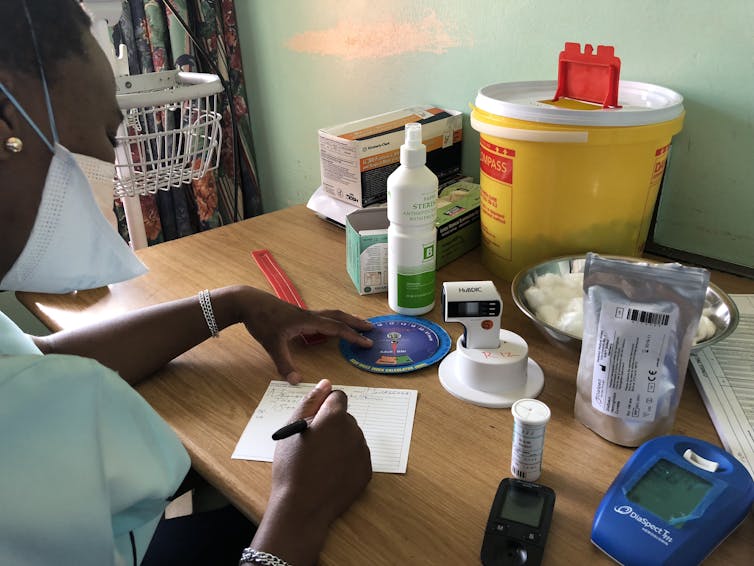

![]() Universal health coverage requires essential diagnostics, and diagnostics cannot be delivered without investments in health systems.

Universal health coverage requires essential diagnostics, and diagnostics cannot be delivered without investments in health systems.

Madhukar Pai, Director of Global Health & Professor, McGill University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.