Photo: EVerton Vila/Unsplash.

The following article, republished from eLife, a scientific journal, omits references and links to the survey data. These details are available on the page of origin.

As concerns about poor academic mental health grow, it is also becoming clear that certain individuals in the community try to help those going through a difficult time. Yet these relationships remain poorly understood, putting them at risk of being overlooked by institutions.

In response, eLife collaborated with scientists to release, in late 2019, a survey that examined the experiences of those who support researchers struggling with their mental health. The final dataset captures the voices of over 1,500 respondents in various academic roles. The results – relayed in detail in a report – paint a complex picture of the needs and experiences of these ‘supporters’.

In this article, we share five main findings – as well as our dataset and code – for those who strive to improve mental health in academia to build upon. While many of the pressures that supporters experience are deeply embedded in the way academia currently operates, a better understanding of what these individuals do and need may help to pave the way for change. As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds and exacerbates the academic mental health crisis, these discussions are urgently needed.

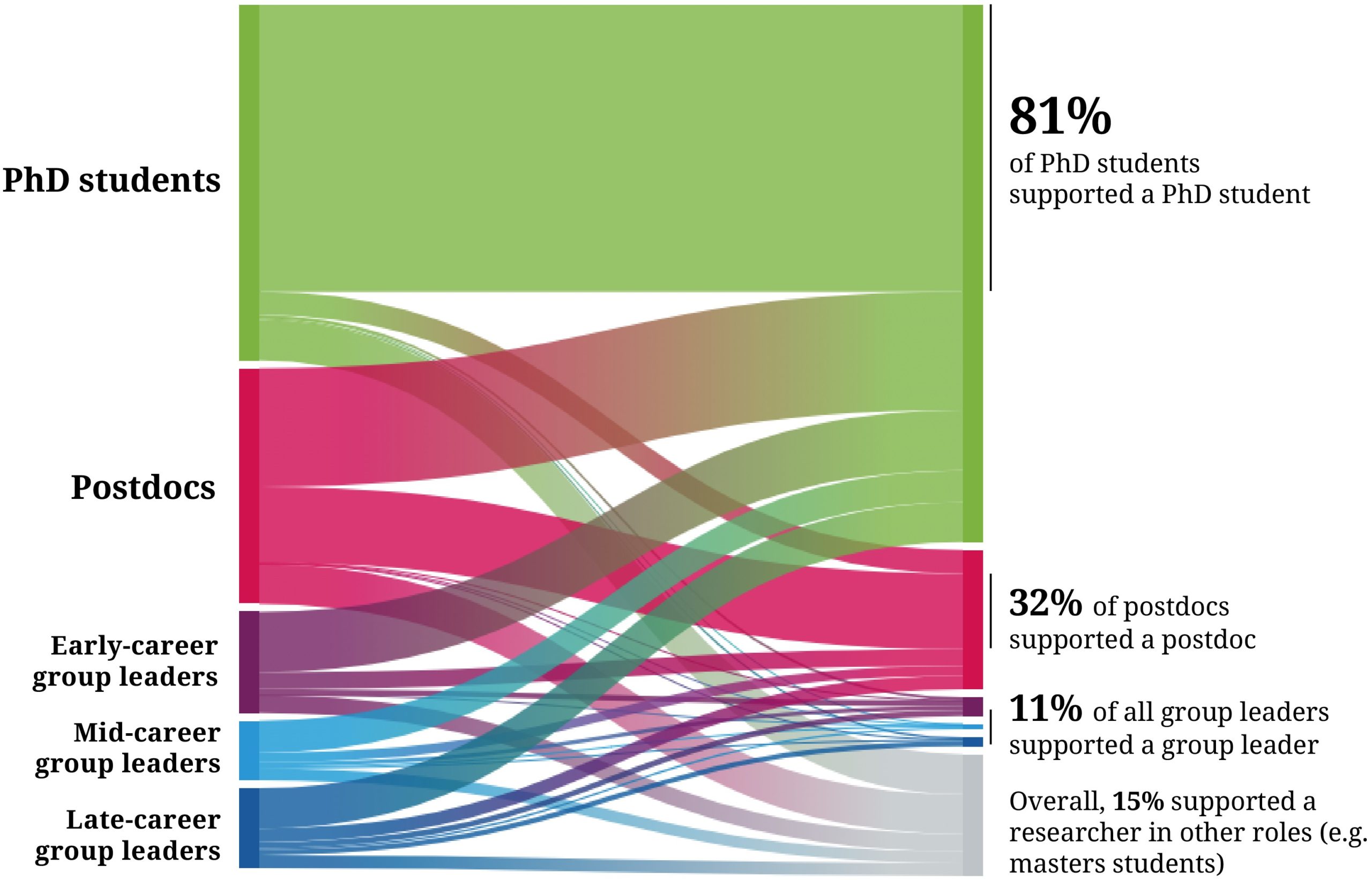

Peers often support peers

Our results indicate that, at least for our sample, supporting colleagues who struggle with their mental health is a common occurrence in academic settings: about two thirds of respondents have already helped more than two individuals. These interactions mainly take place between peers at the same career stage – especially for PhD students and postdocs – or flow from an established to a more junior researcher. Many researchers, including group leaders, also provide support to colleagues who they have no official responsibility towards. “It’s a thankless job but somebody has to do it,” said one postdoc. “Providing secondary mentorship (disciplinary, hidden curriculum stuff, and emotional) is critical to making the ‘trains run on time’.”

Failure to acknowledge that help is offered by many populations, including peers and non-academic staff, runs the risk of leaving a large proportion of these informal supporters without the backing they require. “I had no outside assistance,” said one respondent. “I don’t know if there are particular guidelines in place for assisting individuals who assist others with mental health problems. As a postdoc (a long-term one), I am excluded from these types of information workshops because I am not a ‘supervisor’.”

Our results also highlight that only a minority of supporters help early-career group leaders, despite this population also reporting being under considerable pressure. “I wake up every day feeling overwhelmed and I often have upsetting situations and almost no one to talk to about it,” replied one early-career group leader. “This is the worst time of my academic career and of my life right now.”

Complex needs, complex support

The survey responses paint a picture of in-depth, long-term relationships that involve several types of support and address a range of mental health issues – at least as perceived by supporters. About two thirds felt that the individuals they helped were struggling with depression/low mood and anxiety, but some also reported supporting individuals who experience conditions associated with high-risk for harm, such as sleeping problems (29.5%), suicidal thoughts (16.1%), self-harm (6.5%), substance abuse (7.3%) and eating disorders (6.1%).

Supporters also believed they had helped individuals whose conditions were, as far as they knew, connected to traumatic events that had taken place in academic settings, such as bullying (20.9%), sexual assault or harassment (5.4%), and racism (7.7%). Despite the potential severity of these conditions and experiences, almost half of supporters had helped someone who, at least at some point in the relationship, was not receiving professional help.

Nearly all supporters provided emotional support, but over half also suspected someone needed help, and proactively encouraged this person to open up. Many also gave advice about how to manage one’s mental health (46.6%) and about resources that could be accessed (50.6%). Supporters also provided practical help – often with work (41.7%) – and almost a quarter advocated for a colleague, such as requesting additional help on the person’s behalf. These supporting relationships were also not short-lived: most lasted for over six months, and about a fifth for over a year.

A positive experience, but poorly supported

The majority of respondents found that helping someone was a positive experience – “one of [my] most rewarding experiences in grad school”, as one PhD student put it – and most felt appreciated by the person they had helped. For one respondent, the “pursuit of knowledge is meaningless if uncoupled from a sense of shared humanity with our colleagues.”

Yet, 76.1% of supporters felt this role was emotionally draining or stressful. “We were not prepared to deal with the issues”, recalled one postdoc, “and we were constantly scared of giving the wrong advice, and the repercussions that [it] could have.” It is not surprising, then, that only about a quarter of supporters reported not needing emotional support – with nearly 20% needing but not accessing this type of help. Family, partners and friends outside of academia were the main source of emotional support, suggesting that work issues spill over to the personal sphere and that institutions may be failing to fulfil that need.

“My department sent one email, last year, which essentially told lecturers off for not ‘practising self-care’, and gave the reason why we should do so as [being] that students need us to be good role models”, recalled one PhD supervisor. “That email actually made me cry with frustration. I feel angry, inadequate and exhausted all the time. I’m just expected to fix the problems with no thanks or support, no one to turn to, and the threat of complaints if I don’t manage it.”

Certain supporters face specific challenges

Across the board, women who were supporters faced additional challenges compared to men. At the time of support they were more likely to be helping several people, to be struggling with their own mental health, and to be feeling less supported or valued by their institutions for helping someone. Women were also more likely to report that other people approached them because they were known as supporters. “I am repeatedly frustrated by my (often male) colleagues’ stated belief that ‘there is no mental health problem’ at our institution,” said one female mid-career group leader. “They don’t know about it because their trainees come to me, not to them, with their issues. I receive no institutional recognition for this role.”

In parallel, women felt their supporting role was more emotionally draining or stressful, more time-consuming, and impacting their personal lives and work more compared to men. Further analyses are needed to confirm these results and disentangle how these experiences emerge, interact and reinforce each other: yet these findings are consistent with literature on how gender influences academic experiences.

Overall, those new to leadership positions also emerged as a group with specific needs; compared to individuals at other career stages, they were more likely to find that supporting someone had an impact on their work and left them drained or stressed. Navigating a supporting relationship as first-time supervisors could come with specific challenges, such as learning how to professionally manage a distressed junior colleague, and the resulting group dynamics. “I was afraid I was providing the wrong kind of support, was afraid I would be blamed as the cause for additional stress”, recalls a mid-career group leader. “What was expected out of [the distressed junior colleague] was low, but the illness was not known to the group. It demotivated the group as others thought I did not have uniform standards for everyone.”

Over three quarters of respondents reported having gone through times when their mental health was poor, suggesting that our sample is enriched in people having faced mental health issues. “It is generally the ones who struggled with mental health themselves who step up and care”, remarked one postdoc, “but they need help, too.” This also means that many were struggling themselves while providing support – 83.8% of PhD students were in that position, for instance, and 23.9% of senior group leaders. This overlap between those who need and provide support may suggest that information on how to appropriately help others should be included in initiatives designed for researchers who experience mental health issues.

It would be crucial to also explore whether supporters with first-hand experience of poor mental health or who belong to underrepresented communities are more likely to provide support, and experience it differently compared to other groups. “This feels especially hard as a woman of colour with my own mental health struggles who tries to be supportive to other women of colour”, said one PhD student. “I ended up playing supportive roles because people could not access mental health services.” Understanding these interactions is particularly important since mental health issues may disproportionally affect populations already marginalised in higher education. This could potentially triple the invisible workload of people who live with these health conditions, are underrepresented, and support other at-risk individuals.

Structural barriers hinder support

While about a third of those providing support said it had affected their work, just over half reported that it was taking a lot of time. Yet only 3.6% strongly agreed that their institutions valued or supported what they were doing. “Universities need to acknowledge this as work, for example in workload models, professional development or promotions discussions” said one university lecturer. “‘They’ love and need us to do it but don’t support it. Many mental health supporters around me are fed up and burning out.” Not valuing the help provided by supporters may lead them to worry their efforts are viewed negatively – one mid-career group leader recalls hearing: “Why are you doing all this work? They just need to go see a therapist!”

Most have also faced situations where they did not support someone who needed it. In particular, 49% of respondents cite struggling with their own mental health as a reason for not providing help: “It becomes difficult to be a good mentor for others when you are dealing with your own mental health problems” commented a group leader. Yet, 39.2% also explained finding that the person was difficult to approach. “Stigma is everything”, explained one postdoc: “It is very difficult to offer support openly since most people prefer to hide. I understand very well this feeling.”

A PhD student concurred: “I wished that there was less stigma associated with needing and getting help. It’s hard to seek or accept help, or tell others to seek and accept help, when it is still seen as a weakness.” In turn, the weight of stigma could amplify confidentiality issues, making it more difficult for supporters to manage the supporting relationship and to look for help for themselves.

The hierarchical nature of the research community may have also stifled support: just over a fifth of supporters did not provide help for fear it would put them in a difficult position. One postdoc put it bluntly: “They were being bullied and I thought I would get bullied too.” In fact, a number of respondents regretted not standing up for a colleague, especially in cases of abuse. “I wish I could have been an intermediary between them and the PI”, recalled a respondent who was a postdoc at the time, “but that puts the ‘helper’ in a potentially bad situation.”

Finally, many respondents noted in their comments that the culture of modern research, such as a relentless need to publish, large numbers of fixed-term contracts, inflexible funding deadlines and heavy workloads ultimately fosters an unhealthy environment that hinders support as well as creates mental health issues. One early-career group leader summed it up plainly: “Given that ideas, papers and grants are the metrics for success, is it any wonder that trainee mental health is sacrificed?”. The COVID-19 pandemic, which has delayed many research projects, increased demands on teaching staff, led to hiring freezes, and placed additional pressures on those with caring responsibilities, may worsen this situation.

What next?

Ensuring that all supporters – not just group leaders – receive help, training and recognition may be key to fostering healthy, positive relationships between those who provide and receive support. At present, the practical and emotional help that supporters need is found outside the institution, or it falls on colleagues – potentially raising confidentiality issues for the supported individual.

Our results may highlight the need to go beyond one-off training sessions and provide on-going help for supporters, especially since most turn to conversations with other people for advice, rather than other types of resources. Such help and support also needs to take into account the full range of conditions and problems found in the research community: “I think people are becoming better at discussing overall depression and anxiety”, said one PhD student, “but they still struggle to discuss suicide, self-harm, hallucinations, and other areas of mental health they perceive as ‘more serious’.”

However, unless the root causes of poor academic mental health are addressed, these measures could, in the words of a respondent, be “sticking plasters” at best. Ultimately, no amount of training or awareness-raising can change the fact people may not have space, time, and emotional resources to actually provide support. And while a collegial approach has some advantages, relying on researchers to monitor and be responsible for the mental health of their colleagues also raises issues.

As a PhD student remarked: “It’s important that this does not become a thing where people who are struggling need to out themselves in order to receive help. They are entitled to maintain their privacy and not to have to discuss this with their colleagues unless they want to.”

Our results raise many questions, and we hope the community will criticise and build upon this work. In particular, the factors which may predispose certain individuals to become supporters (such as gender or minority status), or which could make this invisible workload more difficult (such as supporting someone who is not helped professionally) should be carefully assessed. Supporting relationships will also need to be re-examined through the lens of the 2020 pandemic: in a socially-distanced, remote working environment, how will informal peer-to-peer support take place? Who will spot early, subtle signs of distress? Who will have the emotional bandwidth to answer them?

In the short-term, we hope our results will bring the work of supporters to the attention of institutions, and encourage reflection on how to value and support these individuals. A first step could be to better understand supporting relationships at the local level (e.g. in a department) to assess specific needs, create tailored solutions and evaluate the impact of interventions.

We also wish for the survey to empower supporters, helping them break the isolation they may experience, and encouraging peers to enquire about the wellbeing of individuals who provide help as well as of those who need it. And most importantly, for those who struggle, we hope they hear the voices of supporters who, in their open answers, reaffirmed their commitment to help, their sadness at seeing peers struggle, and their deep-set belief that, in the words of one respondent: “The presence of a mental illness does not impair an individual’s ability to do great science.”

Elsa Loissel is an associate features editor at eLife, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

This article was originally published by eLife journal and and has been republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution license. Read the original here.