Normal red blood cells next to a sickle-shaped cell. Image: OpenStax College/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0

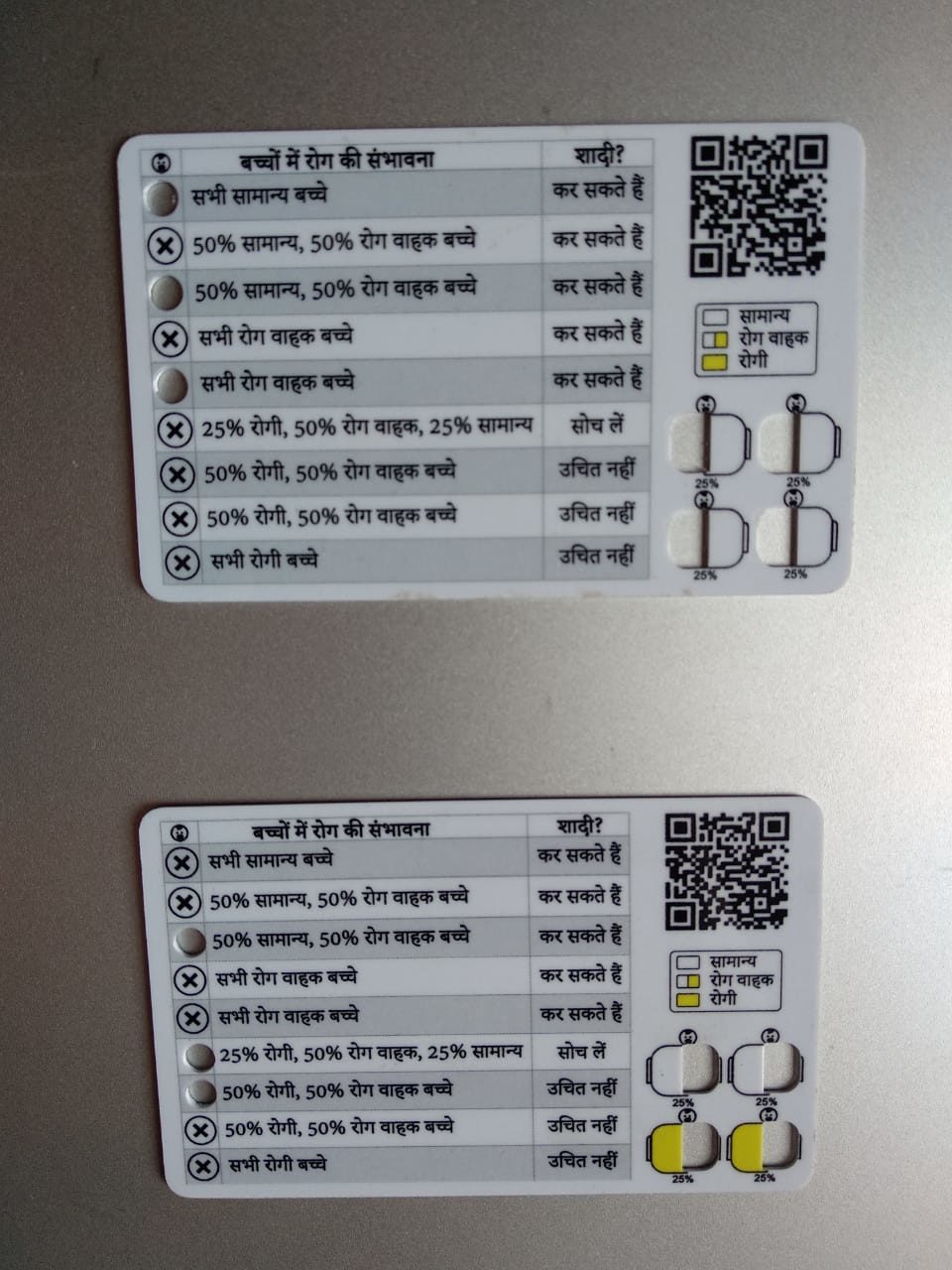

- In November 2021, on the birth anniversary of freedom fighter Birsa Munda, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched “gene cards” in Madhya Pradesh.

- These cards indicate a couple’s chance of having offspring with sickle-cell anaemia, calculated based on a couple’s genetic composition, which is marked on their individual cards.

- In India, sickle-cell anaemia is largely found among tribal, Dalit and a few OBC communities, and to a lesser extent among people of other communities.

- It’s a neglected disease that affects a neglected people. Any scheme that doesn’t address this neglect can’t help reduce the disease’s prevalence.

In November 2021, on the birth anniversary of freedom fighter Birsa Munda, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched “gene cards” in Madhya Pradesh. These cards indicate a couple’s chance of having offspring with sickle-cell anaemia, calculated based on a couple’s genetic composition, which is marked on their individual cards.

“A similar exercise was conducted in 2006 in Gujarat, where mass level screenings were done in the tribal communities and people with sickle-cell disease were handed yellow cards. But what was the next step?” asked Prasanna Saligram, a health policy research scientist with the Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, Karnataka. “People were branded for life and stigma against them rose within the community.”

Sickle-cell anaemia is the result of a genetic mutation occurring in communities that originally inhabited areas affected by endemic malaria. Over time, the gene corresponding to haemoglobin in their bodies mutated to resist plasmodium, the parasite that causes malaria. This changed the shape of red-blood cells from round to sickle-shaped. As a result, these people experience pain, eye problems, infections, even stroke and potential damage to multiple organs in the body.

Different forms of the same gene are called alleles. If a person has two alleles of the defective haemoglobin gene, they’re said to have homozygous sickle-cell disease. If they have only one defective allele, they’re said to have heterozygous sickle-cell disease.

People with the homozygous variety experience the typical symptoms of sickle-cell anaemia and have lower life-expectancy. Those with heterozygous sickle-cell anaemia live relatively healthy lives – but can pass on the gene to their offspring.

In India, sickle-cell anaemia is largely found among tribal, Dalit and a few OBC communities, and to a lesser extent among people of other communities.

There is no consolidated government data on the disease’s exact prevalence; instead, there have been sporadic efforts by individual medical researchers and institutions. One study estimated that the disease’s prevalence in India’s states ranges from 0% to 40%. The prevalence also varies between communities, which means there needs to be community-focused strategies for data collection and intervention.

Rahul Singh, a sickle-cell anaemia program coordinator at Jan Swasthya Sahyog, easterm Madhya Pradesh, said that in 2018-2021, they had screened 1.8 lakh people of around 36,000 families, in six districts. Of them, 16,000 people had the sickle-cell gene, and of them, more than 2,000 were homozygous and the rest were heterozygous. Some 83% of the 36,000 families were below the poverty line.

“Since the nature of the disorder is genetic, we screened through contact tracing within the family. We found that one in three family members was sickle-cell gene positive while the positivity rate was as high as 15% among pregnant women,” Singh said.

§

Saligram started working with the sickle-cell project in Gujarat in 2013. He said our public health system is dominated by the biomedical approach: focused on distributing medicines and solutions over building culturally sensitive, community-based prevention programs that empower people to make decisions related to their health.

But even among fairly neglected diseases in India, sickle-cell anaemia is further neglected because it isn’t a disease of the privileged. For example, a 2020 report by The Economist (sponsored by Novartis) found that support systems for children in India with thalassaemia and haemophilia had reduced their dropout rate from school, but that children with sickle-cell anaemia didn’t have a similar system.

“Both sickle-cell anaemia and thalassaemia are outlier diseases for our public health system because they only impact certain groups of people in certain geographical areas,” Saligram said. “However, thalassaemia has received comparatively more attention because it was also found in groups from affluent communities – such as Sindhis, Punjabis, Jains, etc., who were able to form their networks and advocate for an increase in the profile of the disease.”

Sickle-cell anemia, on the other hand, affects people born in tribal and Dalit families.”

Access to healthcare

There are innumerable accounts of people’s lived experiences with sickle-cell anaemia that show that their health outcomes are the result of socio-economic inequities – typically unequal access to hospitals due to poor road connectivity, no/weak mobile networks, shortage of ambulances, high cost of commute to hospitals, crowded health centres, and lack of sufficiently trained doctors and lab technicians.

Often the closest health facility for people with sickle-cell is either a district hospital or a hospital in a major city. But since people with sickle-cell anaemia are often quite poor, the cost for treatment is extremely high. They lose their wages and often their livelihoods, as well as need to spend time and money to travel and to be treated.

Also read: Does India Know Anaemia Is Running Amok in the Country?

Low literacy and awareness among members of the affected communities also leaves them vulnerable to being ‘treated’ by local healers, who often brand people with sickle-cell anaemia with hot iron for pain relief.

“During our intervention in the Jhirniya block of Khargone district, which is dominated by Bhil, Bhilala and Barela tribes, another factor impacting health outcomes of patients of sickle-cell anaemia were frequent droughts,” Vishan Devda, sickle-cell program coordinator of an NGO called Synergy Sansthan, said. “Sickle-cell patients require more water than others because the water helps to increase blood flow and prevents episodes of excessive pain.”

However, according to Devda, Khargone district has a bad water crisis and members of the tribal communities are disproportionately more affected, thanks to systemic barriers. Devda said that as a result many children with sickle-cell anaemia don’t “survive into adulthood, even when there is a chance for them to live longer, healthier lives.”

In India, 20% of children with the disease die before they turn 5 and 30% don’t reach adulthood. Jan Swasthya Sahyog’s 2018-2021 reported found that 60% of those with sickle-cell disease are school-goers, and only 0.8% of those with the disease were older than 50 years.

Singh also said more people with sickle-cell anaemia had died during the COVID-19 than in similar periods earlier, mostly due to poor access to public transport, high cost of private transport and drug shortage at community health centres.

Cycle of violence

In 2019, I visited the house of a Bhil family in Khargone that had been found to have the mutated sickle-cell gene. The family members asked me if I would drink the water in their house. I didn’t understand the question, so they explained that people in their neighbourhood had stopped visiting them or eating at their place after they had been diagnosed with the disease.

The ‘gene cards’ that Prime Minister Modi launched in November 2021 threaten to exacerbate such social ostracism. Modi launched the gene cards on a large platform, without a pilot programme and without formally assessing its social outcomes. Experts, health workers and activists now worry that widespread adoption of the cards could add another layer to the local social hierarchy and perpetuate emotional, economic and social violence against the very people the cards were designed to help.

Notably, sickle-cell anaemia is often described as a “tribal” problem, including in official reports and research papers. After Modi launched the gene card, the state invited three members of a tribal community to receive the first cards. In an informal conversation in Madhya Pradesh in 2018, one local official told me that he blamed the tribal culture of endogamy – marrying among one’s own – for the spread of the disease, and contrasted it with the “superior” Hindu practice of marrying in a different ‘gotra’.

Also read: Factcheck: Haryana CM Khattar Doesn’t Have Science’s Support to Ban Same-Gotra Marriages

Singh, however, said that his organisation had recorded the presence of this disease among “families from all castes” and not just tribal communities.

Devda called sickle-cell anaemia a political issue because differential, poorer health outcomes in patients with the disease are a result of socio-economic deprivation and years of oppression, which disempowers the community by blaming them and their culture for its spread.

The public health system “will hand them cards and tell them whom to marry. And when people don’t follow it, [the system] will blame the people only for having sexual intercourse and having children who have the disease,” Saligram said. “This results in a circle of oppression.”

Instead, he added, it’s important to screen pregnant women as well as to design a community-based programme that asks – and answers – how many women from tribal, Dalit and other marginalised communities actually reach any health centre for their antenatal checkup.

The National Health Mission is about to finalise and release its new national guidelines on the prevention of haemoglobinopathies[footnote]Conditions that affect haemoglobin[/footnote] in India. (See the 2016 guidelines here.) The draft guidelines, which this author has seen, focus on screening and creating sickle-cell disease treatment centres over community-based prevention strategies. These centres will be a waste if people are unable to reach them. Instead, we need a public health system that begins by addressing socioeconomic deprivation.

Divyaa Gupta is a development professional with an extensive experience of working on gender-related issues. Currently, she works as a freelance consultant, assisting organisations in mainstreaming intersectional gender approaches in their workplace policies and programmes.