A representative image of a PET scanner. Photo: Jens Maus/Wikimedia Commons.

Guwahati: At the Dr Bhubaneswar Borooah Cancer Institute (BBCI) in Guwahati – the sole full-fledged cancer care centre in India’s northeast region – patients and their families wait anxiously for their turn to meet the doctor.

Dilip Das (34) from Barpeta has been in the building for a while now. “They say my father’s gallstones aching the belly might have spread too far,” Das told The Wire Science. “He has been on oxygen support in the ICU for 7 days.” His anxiety pushes him to ponder death. Being in the “ICU costs Rs 25,000 every day. Daily travel costs Rs 5,000. My friends lent about Rs 2 lakh. I cannot arrange for more. My father is old already. What if he dies?”

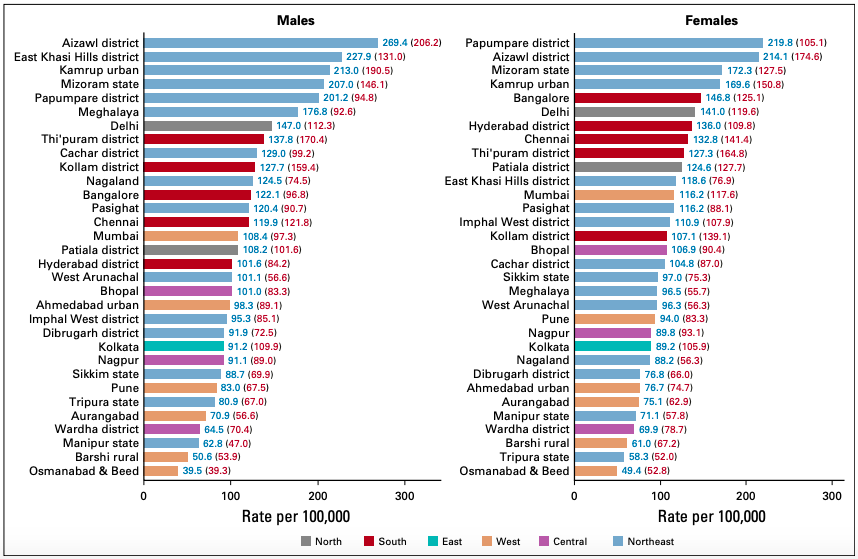

According to a National Cancer Registry Programme (NCRP) report, Northeast India had the highest incidence of cancers among both sexes between 2012 and 2016, of all of India’s regions. “The leading sites of cancer” here, it read, “were nasopharynx, hypopharynx, oesophagus, stomach, liver, gallbladder, larynx, lung, breast and cervix uteri.”

The figures in Aizawl district, Mizoram, and Papumpare in Arunachal Pradesh are particularly worrisome: 269.4 and 219.8 among men and women respectively, per lakh population. They are followed by East Khasi Hills, Meghalaya – 227.9 per lakh – and Kamrup (urban), Assam – 213 cases per lakh.

The NCRP report attributed local cultural factors for the heterogeneity in cancer incidence in India. One implication of this is that pulling down the number of cases will require lifestyle and behavioural changes, which are difficult to effect. However, blaming cultural choices also risks sweeping other, eminently more manageable problems – and the responsibility to address them – under the rug.

For example, cancer patients in the northeast have a hard time accessing cancer care and treatment. The hilly terrain is tricky to navigate even on better days, and there aren’t nearly enough hospitals and healthcare workers at the primary and secondary healthcare centres to direct patients to the relevant facilities and resources.

And now the country’s COVID-19 epidemic, aided by the nationwide lockdown, has only made matters worse – so much so that many patients have had to skip chemotherapy sessions.

Gaurav Pramanik (34), a social and environmental activist from Sikkim and North Bengal, preferred chemotherapy at home. “Every time I go to the hospital, there will be a COVID-19 test. And once you test positive, you will be isolated, which is not ideal for a cancer patient,” he said over a phone call. He is also wary about visiting the hospital for fear of becoming infected there.

Also read: Explainer: What Is a Healthcare-Associated Infection?

The BBCI’s patients footfall fell by 50% during the lockdown period. A little under 6,000 patients had visited the facility from February 18 to March 24, when the lockdown kicked off. So between then and May 1, only 3079 patients came. Similarly, the number of chemotherapies dropped 42%, radiotherapies 56% and surgeries 74%. Most of those who were diagnosed with cancer during the lockdown period were affected in the gall bladder. Gall-bladder cancer is often diagnosed in the advanced stages, which means those who can’t access treatment on time are more at risk of debilitating outcomes.

In the OPD building at BBCI, a mother waits in line for her three-year-old’s chemotherapy. At one year and 11 months, her child was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia – a cancer of the blood cells that can rapidly worsen if not treated on time.

Fortunately, with help from two NGOs, her child’s condition improved significantly after intensive care for a couple years. The organisations arranged for the family’s consultations, food and lodging. But their assistance has since expired, and now she is nervous about her and her partner’s impending expenses.

BBCI ranks third in the list of institutions for the efficient implementation of the Ayushman Bharat Yojana scheme. In the last two years, it has provided free treatment for up to Rs 5 lakh to 9,811 patients. Patients at BBCI can also avail Assam state’s Atal Amrit Abhiyan scheme, which covers medical expenses of up to Rs 2 lakh per family.

Outside these schemes, however, the costs are not exactly affordable. The 75th round of the National Sample Survey estimated the average total cost of cancer care (per hospitalisation) to be Rs 22,520 in public hospitals and Rs 93,305 in private establishments. These costs may seem to be covered under, say, the Meghalaya Health Insurance Scheme, the Rashtriya Arogya Nidhi, the Dr Ambedkar Medical Aid Scheme and the Chief Minister Relief Fund – whose ceilings range from Rs 1 to 3 lakh. However, the actual costs are often higher, more so if there are complications or if the type of cancer is rare.

For example, Pramanik has non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which requires a chemotherapeutic regimen of four drugs: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP). And “out-of-pocket expenses for a round of CHOP would come to a maximum of Rs 60,000,” Pramanik said. “Even if the entire package is subsidised, it would still be around Rs 8,000 – which is expensive for lower-income patients.”

State-backed schemes for healthcare in states such as Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim and Tripura are on the anvil, but it is not clear if they can improve patients’ expenses any more than other schemes already do. Dr Niju Pegu, a surgical oncologist in Guwahati, said that in effect, the existing schemes covered too little “to fight cancer”.

Then again, high costs enter the picture only if they are incurred in the first place – and this is difficult as well given the poor infrastructure.

According to Dr Vikas Jagatap, the secretary of the Association of Oncologists of Northeastern India, there is one radiotherapy machine at the Shillong Civil Hospital in Meghalaya, and a three-year-old machine at the Tomo Riba Institute of Health and Medical Sciences, Naharlagun, Arunachal Pradesh. There are two radiotherapy machines in Nagaland: one at the Christian Institute of Health Sciences and Research and the other at Eden Medical Care Centre, both in Dimapur.

“Patients in Manipur were left helpless when the radiotherapy machine at the Regional Institute of Medical Sciences in Imphal shut down for a while,” Dr Hari Krishna, a doctor at the institute, said.

Tripura has one internal radiotherapy machine at the Regional Cancer Care, Agartala. Mizoram has zero. In (bare) addition, Sikkim has only one cancer ward at the Sir Thutob Namgyal Memorial, Gangtok. Barring Guwahati, there are no PET scan diagnostic centres in the region.

One quantifiable correlate to this technological poverty is that, according to the NCRP report, “the northeast region [has a] low five-year survival of breast, cervix, and head and neck cancers compared with the rest of India.”

If there had been a cancer-screening facility in Assam’s Udalguri district, Arati Sinha wouldn’t have had to spend Rs 30,000 to procure saline and vitamins for her 62-year-old husband’s leg pain – nor have to bank on rudimentary remedies for his cough. When she could afford it, she took him to a private hospital in Tezpur, a 100 km away, where a biopsy indicated he may have bone cancer. The duo has since travelled to BBCI, in Guwahati, for another biopsy to confirm.

“It is very much the need of the hour that every state in the northeast should have at least one tertiary centre for cancer treatment considering the cancer burden in the region and basic diagnostics facilities at the district level,” Dr Pegu said.

Also read: Why Everyone Around You Seems to Be Getting Cancer

The northeast’s cancer incidence is commonly attributed to high consumption of tobacco products, fermented foods and betel nuts. Some doctors this correspondent spoke to also said Meghalaya and Nagaland in particular have more than their fair share of oesophageal and nasopharyngeal cancer cases, and Manipur, of head and neck cancers.

However, one doctor at the Eden Medical Care Centre in Dimapur cautioned that multiple factors could affect the development of nasopharyngeal cancer – just as head and neck cancers could arise from a combination of genetic and environmental changes. Pramanik said he has “known people with lung and mouth cancer who have never touched tobacco in their lives,” and said it would be imprudent to blame lifestyles alone.

Aatreyee Dhar is a freelance reporter covering the northeastern belt for NewsFileOnline, a media organisation kickstarted by the employees of The Telegraph Northeast.