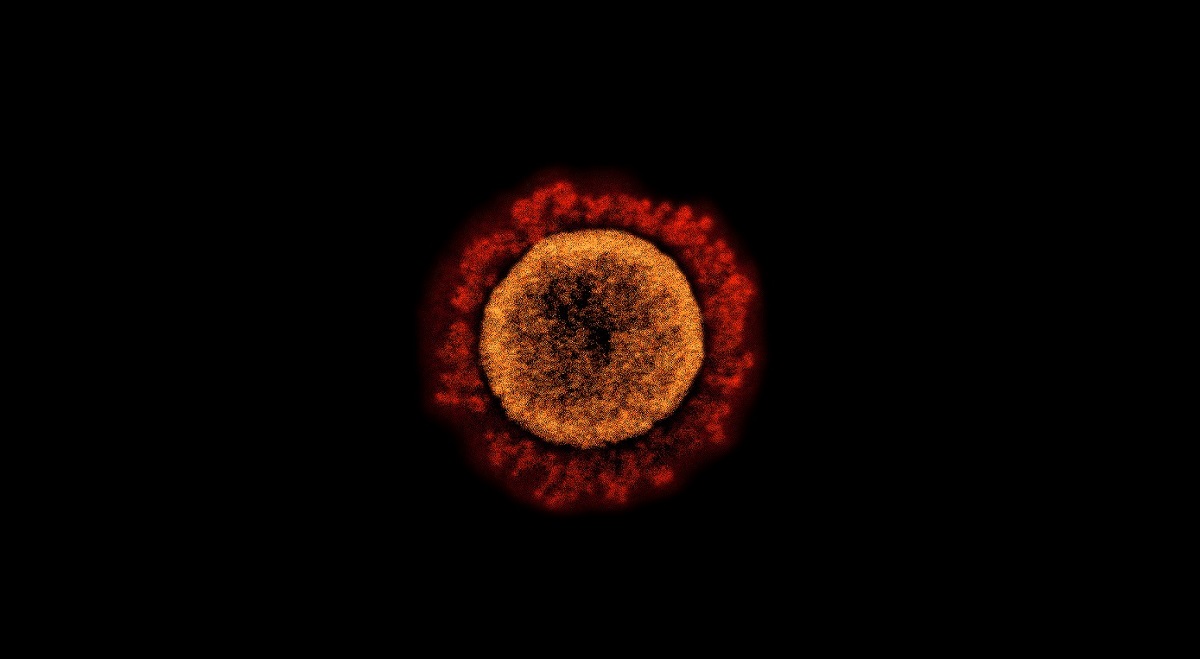

Transmission electron micrograph of a SARS-CoV-2 virus particle. Photo: NIAID/Flick CC BY 2.0

Just as the world is gradually reopening, the newest SARS-CoV-2 variant, described in the popular press dramatically as lethal and dangerous, and ominously as apocalyptic in social media, was reported just a few days ago.

First identified in Botswana and soon thereafter in South Africa, this new variant appears to have quickly spread to many other countries. It has been detected in Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Denmark, Austria, Belgium, Germany, Italy, England and Israel. The list is bound to grow. This is triggering lockdowns and travel bans in many countries and brings with it an awful sense of déjà vu, especially for citizens in South African countries. Is the emergence of this new variant a sign for us to be cautious or is it a dire warning that spells disaster?

South Africa just got past its third wave, fueled by the Delta variant, in the first week of November this year. From over 300 COVID-19 cases a day per million population, in the first week of July, the country’s case load dropped to less than 5 confirmed cases per million during the first week of November. But in the last 3 weeks of November, the number of South African citizens contracting SARS-CoV-2 infection has risen by about five fold. At this time, we do not know if this marks the beginning of the next wave in South Africa or if the current uptick is a mere blip which may subside eventually.

Coincident with the uptick in COVID-19 cases, the South African Network for Genomic Surveillance noticed increasing numbers of COVID-19 patients infected with a new variant of SARS-CoV-2, which they identified as B.1.1.529. The first confirmed case of infection with this new variant was identified in the 2nd week of November. By 20th November, the South African health authorities had confirmed close to 80 cases of infection by the new variant, all in the Gauteng province of Johannesburg. South Africa intimated the finding of this new variant to the World Health Organisation (WHO) on November 24th and to the world the next day. The WHO designated the B.1.1.529 variant as a variant of concern (VOC) and named it Omicron on the November 26th, 2021.

Why did the WHO designate Omicron as a VOC?

One of the major reasons for the WHO considering Omicron a VOC is the fact that it is a heavily mutated version of the parental SARS-CoV-2 that started the pandemic. It is genetically distinct from the previous variants. In that sense it is an unknown entity.

What does ‘heavily mutated’ mean? The genetic information of SARS-CoV-2 is based on a four-letter alphabet, which is about 30,000 letters long. When the virus multiplies within infected cells, it makes millions of copies of itself, a process which also requires the making of millions of copies of the genetic information, with one copy for each new progeny virus. During this copying process, some errors creep into the newly minted copies of the genetic information.

For example a wrong genetic alphabet could be used during the copying process. Sometimes this letter change may result in changing the genetic information dramatically. Virologists call such a genetic letter change as a mutation. Mutations happen at a low but finite frequency as a normal part of the life cycle of the virus in an infected person.

Decoding the genetic alphabet is known as sequencing. Scientists who have sequenced the 30,000 letter genetic alphabet of the Omicron variant have identified a unique combination of about 50 mutations, with 30 of them localizing to the spike gene, the part of the viral genetic information encoding the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. These mutations change the genetic information of the spike gene, resulting in the Omicron variant possessing a considerably different version of the spike protein, compared to that of the parental SARS-CoV-2 which set off the pandemic.

Incidentally, these numerous spike gene mutations make it undetectable in RT-PCR tests of nasal swab samples. This is called as S-gene dropout and is being exploited for rapid screening and surveillance of the Omicron variant in South Africa. Currently, most RT-PCR test kits in India are not suitable for such rapid surveillance of the Omicron variant.

The COVID-19 vaccines are designed to induce immunity against the spike protein of the parental SARS-CoV-2. The worrisome question now is: will the Omicron variant, sporting spikes with so many mutations, be so different as to evade the antibodies induced by COVID-19 vaccines? If so, we may see a spurt in Omicron breakthrough infections of vaccinated people.

Of the thirty spike mutations, ten mutations affect a special region of the spike protein, known as the receptor binding domain (RBD). SARS-CoV-2 gains entry into our cells using the RBDs of its spikes. The worrisome questions here are: do the RBD mutations help the Omicron variant enter cells more efficiently? Is that why it spreads so rapidly?

Many of Omicron’s mutations have been seen already in previous variants and are linked to increased infectivity and the capacity to escape recognition by antibodies. But many more of Omicron’s mutations are new, not seen so far. What do these new mutations mean? Would they make the Omicron variant more virulent? Would it cause severe illness?

While the Omicron variant has raised several critical questions pertaining to its infectivity, ability to cause severe disease and capacity to dodge immunity, there is precious little information on it at this early time. Let’s look at what information is available.

Scientists are racing

Is the Omicron variant highly contagious? Reports in print and digital media suggest that the Omicron variant spreads extremely rapidly. That the Omicron variant was first reported just under a week ago in Botswana and is now reported in about a dozen countries, does indicate its ability to spread quickly. We need to remember, however, that viral spread is dependent on prevailing preventive public health measures, covid-appropriate citizen behavior as well as the extent of vaccine coverage.

Assigning a precise R number, a quantitative measure of the virus’s capacity to spread, actually needs a lot of work and time. R denotes the number of people to whom an infected person transmits their infection. This means identification of COVID-19 patients first as Omicron-infected, and then doing diligent contact tracing, testing each of those contacts, their contacts and so on over several weeks, before arriving at a credible estimate of the variant’s R number. While scientists may hazard a guess, they do not have a precise R number for the Omicron variant at this time.

Early indications from South Africa suggest that Omicron infected people suffer from mild illness which can be treated at home. Apparently many of the people seeking medical care, who turned out to be infected with the Omicron variant were under forty and more than half of them were not vaccinated. In fact, less than 30% of South African citizens have been vaccinated so far. This is being interpreted by some as indirect indication that vaccines may be protecting against Omicron infection. However, doctors and scientists need to monitor Omicron-infected patients carefully to understand more clearly the clinical course and severity of disease caused by this variant.

There is no definitive evidence yet on whether the Omicron variant will bypass immunity induced by vaccination. Scientists think that vaccine efficacy against Omicron variant may be blunted, but not totally compromised. This is because the mRNA (Pfizer and Moderna) and vector-based (AstraZeneca vaccine/Covishield, Janssen vaccine and Sputnik vaccine) COVID-19 vaccines induce immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 consisting of both antibodies (specialized immune proteins) that fight the virus by locking on to its spikes as well as T-cells (specialized immune cells), that recognize and eliminate virus-infected cells. Further, in the case of inactivated vaccines, such as Covaxin, which induce immunity against not only the SARS-CoV-2 spike, but against other viral proteins as well, immune escape through the Omicron variant’s spike mutations may be expected to be of low possibility.

A lot of time-consuming field and laboratory work must be done by public health authorities, scientists and doctors. They must gather data on Omicron infections of unvaccinated and vaccinated people, and monitor such patients for their disease symptoms and clinical progression. Scientists also need to culture the Omicron variant in the laboratory and test its infectivity in the presence of different SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (obtained from naturally immune and vaccinated people) using cultured cells. Only then can we begin to expect some clearer answers on the capacity of the Omicron variant to spread and cause disease, and to blunt, or escape from or succumb to natural or vaccine-induced immunity.

Is the pandemic taking a new turn?

The apparently rapid spread of the Omicron variant to several countries within a few days of its first detection is worrying. This is fueling fears that it may spread globally. Would it displace the Delta variant which is currently dominating all over the world? If the Omicron variant proves to be more virulent than the Delta variant, it does not bode well for the world, especially if it can circumvent the immunity induced by the currently available COVID-19 vaccines. In such a situation, truly transmission-blocking, preventive COVID-19 vaccines would need to be developed urgently to save the world. Unfortunately, none of the current crop of COVID-19 vaccines is notable for stopping virus spread.

On the other hand, if the Omicron variant turns out to cause only mild illness, as seen in South Africa so far, it may not be a bad outcome. Perhaps, the variant would establish an uneasy truce with humans, auguring the transitioning of the pandemic into an endemic, restricted to specific regions where vaccine coverage is low.

These are all mere speculation. The real world consequence of the Omicron variant’s emergence on the pandemic’s trajectory is hard to predict. This is because we do not have answers to important questions like: Is the variant more virulent? Will it cause severe COVID-19? Will the current COVID-19 vaccines be effective against the Omicron variant? Or will there be breakthrough infections and severe illness?

The bottomline

Omicron is the fifth VOC identified by the WHO so far. The true threat level posed by this variant is unknown at this time. Mutations it possesses can potentially affect its ability to spread, cause disease and evade immunity. However, there is no hard evidence as yet that the Omicron variant causes serious disease or that it can escape immunity or that it can spread quickly from person-to-person. It is too early to expect such evidence.

With the Omicron variant identified just a few days ago, we have no basis to predict the course of the pandemic. Also, we have no basis to panic. The WHO’s designation of Omicron as a VOC should be taken as call for urgent action by governments and public health authorities worldwide to increase surveillance, testing and vaccination. Citizens around the world, for their part, must scrupulously adhere to Covid-appropriate behavior such as improving indoor ventilation, hand hygiene, properly wearing well-fitting masks, physical distancing, avoiding crowded spaces and getting vaccinated. This will greatly help minimize spread of the virus.

Non-compliance will facilitate the virus to find more and more people to be exposed. The more the opportunity for the virus to infect and multiply, the more the chances it gets to acquire mutations and spawn variants. If we are not careful, and fortunate, we could run out of Greek alphabets to name newly emerging variants. Of course, that would be the least of our worries then.

Scientists are racing to answer the burning questions, raised by the emergence of the Omicron variant, using a combination of field investigations and laboratory studies. This is a time-consuming and laborious exercise. Definitive answers will not be forthcoming soon, as we enter year 3 of the pandemic.

S. Swaminathan is a retired scientist based in Hyderabad. The views expressed here are the author’s own.