The way the US thinks about sex is wrong. Many people believe that biological sex is binary: Either you’re male, or you’re female. But as with many binaries, things are more complicated than they seem.

Sex and gender, for example, are not the same. Sex is our biology – what chromosomes, hormones, genes, sex organs and secondary sex characteristics we have – while gender is how we think of our identity in the context of how norms function in our culture. Understanding gender not as male or female, but rather as a spectrum, is a recent development for many Americans. It hasn’t been a simple transition: Every day, people make countless decisions based on their sex and gender, some of which can provoke debate, like choosing which bathroom to use, or filling out legal documents, or competing in sports.

The science is clear – sex is a spectrum.

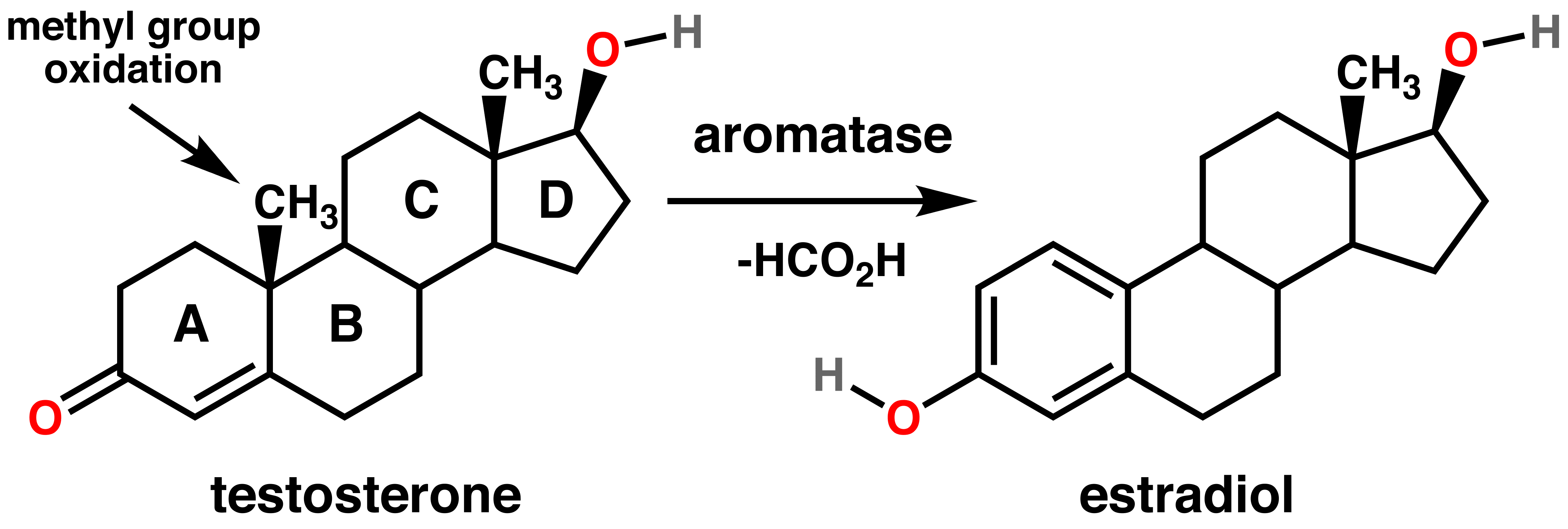

Yet just like gender isn’t binary, our biology isn’t binary either: it, too, exists on a spectrum. In fact, many people’s bodies possess a combination of physical characteristics typically thought of as “male” or “female.” As one example, some people with androgen insensitivity have XY chromosomes, internal testes, and external female genitalia. Traits, including hormone levels, can also vary widely both within and across sexes. But people who fall outside of what’s considered normal face discrimination. Take South African runner Caster Semenya, who was recently the subject of a ruling that ordered her to lower her naturally high testosterone levels to compete with other female runners — even though studies have shown that because testosterone levels are so highly variable, there’s overlap between the natural testosterone levels of men and women.

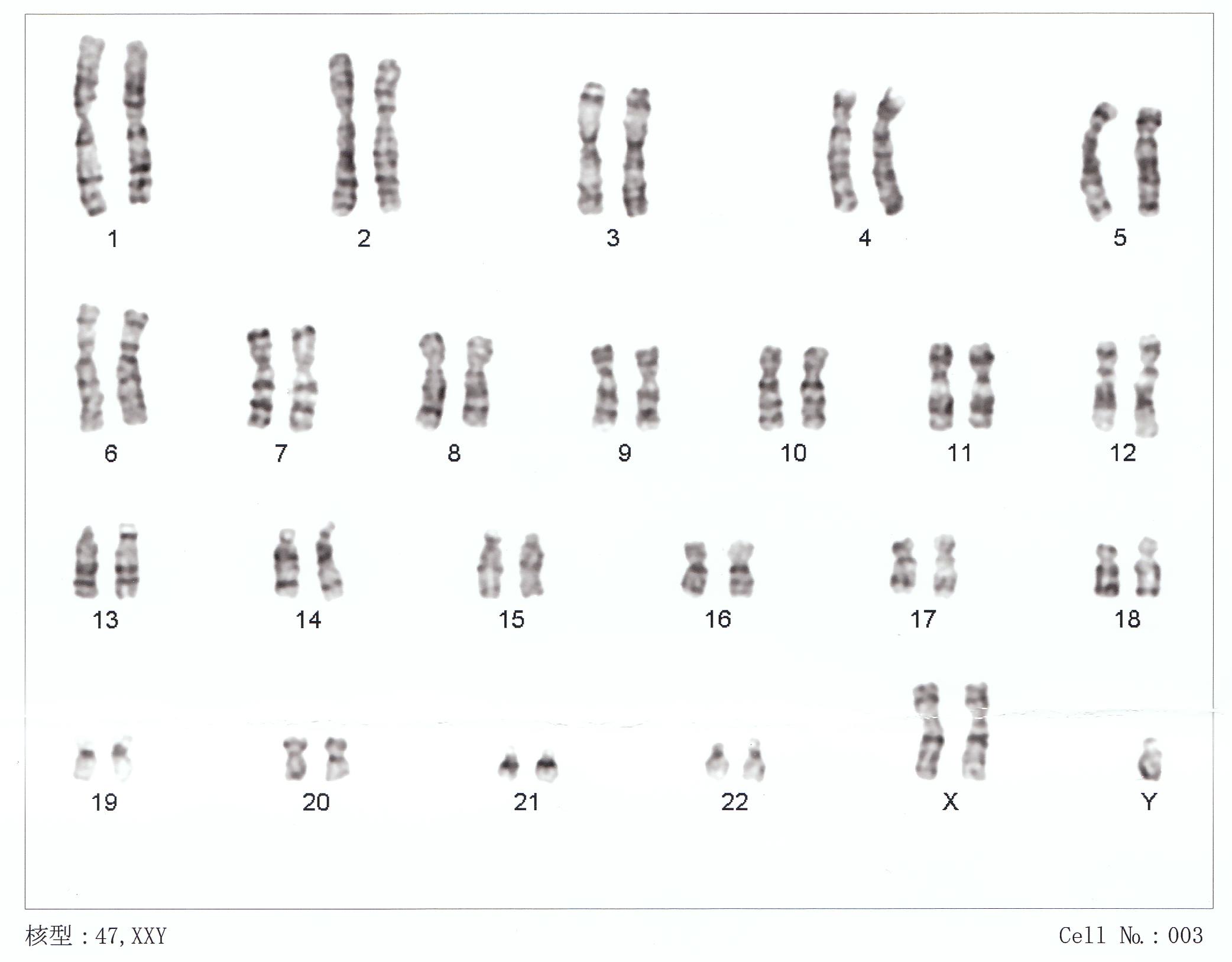

Students are often inaccurately taught that all babies inherit either XX or XY sex chromosomes and that having XX chromosomes makes you female, while XY makes you male. In reality, people can have XXY, XYY, X, XXX, or other combinations of chromosomes – all of which can result in a variety of sex characteristics. It’s also true that some people with XX chromosomes develop typically male reproductive systems, and some people with XY chromosomes develop typically female reproductive systems.

Also Read: Catholic Church Rejects Use of Gender Identity Theory in Education

When embryos first develop, they all start with the same rudimentary reproductive tract – regardless of chromosomes or genes. Later on, during typical embryonic development, embryos with the SRY gene – usually found on the Y chromosome – then develop testes, seminal vesicles, an epididymis, vas deferens, and a penis. If the embryo has a functional WNT4 gene – found on chromosome 1 – and no SRY gene, its reproductive system instead develops into ovaries, a uterus, fallopian tubes, and a vagina.

But sometimes people end up with intersex traits, often referred to in medical settings as differences of sex development (DSD). People may choose to identify their sex as male, female, and/or intersex/with DSD, although many intersex advocates argue against the use of DSD as it implies that they need to be “fixed.” There are many ways people can be intersex. For example, XX embryos with an SRY gene will develop as typical males, while XY embryos lacking the SRY gene will develop as typical females. There are also other genetic variants in several genes that can alter hormone levels, resulting in a reproductive system that is neither strictly male nor female. These changes can cause someone’s reproductive system to not “match” their chromosomes. In the US, when a child is born with ambiguous genitalia, doctors commonly recommend reconstructive surgery to align the child’s anatomy more closely to typical male or female anatomy. It’s been estimated that babies with intersex traits account for up to 2% of live births, with this kind of surgery being performed in about 0.1 to 0.2% of live births – even though evidence suggests this can cause physical and psychological harm.

The complicating problem is that doctors can lack experience treating bodies that are neither male nor female, making it harder for them to understand their patients’ needs. This is true not only for intersex people but for transgender and non-binary patients as well, some of whom may be taking hormones so that their bodies more closely align with their gender identities. Some of these patients may not be seeking affirming medical interventions and want their pronouns respected. Both physical and psychological harm can be caused by the medical enforcement of a sex binary, making it harder for people to seek the medical help that they need in the future.

Harmful approaches to sexual traits carry over to gender because our society often thinks of sex and gender as interchangeable. Laws and social attitudes can make it difficult for intersex, transgender, and non-binary people to receive adequate healthcare services, participate in sports, or be protected from discrimination.

The idea that gender or sex is binary harms everyone by stigmatising traits that lie outside of what society considers normal. Changing attitudes and social structures to recognise sex as a spectrum is a daunting task, but it is possible. To make real change, we need both public education about the biological sex spectrum as well as policy changes. We should ban surgeries on intersex people without their consent and reinstate the Obama-era interpretation of Title IX to enact laws that specifically protect those who are intersex, transgender, or non-binary.

The doctor’s office is often the first place people learn about being intersex, usually when it pertains to themselves or a child. If – instead of recommending that intersex children be raised as either male or female – doctors educated patients and parents about the sex spectrum, it would help people feel accepted in their bodies and change attitudes about what’s normal. But it’s also important to add similar education to traditional sex education in the classroom. Simply teaching about the spectrum of sex can begin to break down stigma.

Also Read: Discussing the Gender Binary, Trans Rights and Social Acceptance With Activist Raina Roy

Currently, discrimination based on sex and gender is widespread. For example, the language used in legal documents like licenses and passports often conflates sex and gender, and in many areas of life, the law offers protection only for binary sexes/genders. Even when certain states, like California, have acted progressively and enabled people to choose non-binary as a gender marker on their driver’s licenses, the federal government has been slow to catch up. This leaves people vulnerable in many ways, including the workplace, housing market, and healthcare.

There are a few positive examples the US could follow: Some countries, including Australia, allow people to self-identify as a third gender or sex. Germany also allows a third sex designation, but only if the person is born with intersex traits. Though there are a few countries that allow for identification as a third sex, they don’t necessarily offer legal protection of this third sex. (Many, for instance, don’t have laws that prevent medically unnecessary surgeries from being performed on intersex people without their consent.) Just creating a new box to fit people in doesn’t necessarily solve the problem.

To truly put an end to sex and gender-based discrimination, we need legislation that considers sex as a spectrum with unlimited options. In some cases, this could be as simple as expanding the language that has been used in laws like Title IX to be explicitly inclusive of all sexes and genders. We also need laws that specifically protect people with non-binary sexes and genders from discrimination in areas like healthcare settings, the workplace, and housing.

The science is clear – sex is a spectrum. Yet the solution to the misunderstanding of sex doesn’t end with scientists. We also need better public education and structural changes to recognise and protect people and their biology.

Liza Brusman, molecular biology, The Scripps Research Institute

This story originally appeared on Massive Science, an editorial partner site that publishes science stories written by scientists.