A worker pulls a rickshaw with passengers through a waterlogged area after heavy rain over Chennai, November 7, 2021. Photo: PTI

Many parts of Chennai have been inundated after heavy rains – up to 22 cm – last night. The city, like all others in India, faces a wide range of issues, and is unlikely to solve any of its problems related to urban flooding within the next 10 years.

Here’s why.

The Chennai Metropolitan Region, in particular the part of the city managed by the corporation, has relatively flat terrain and is very close to sea-level. Agricultural activity in the region required, and prompted, the construction of thousands of large yet shallow lakes.

Over the years the city grew in size and many places, like South Chennai (marked below), expanded into low-lying areas and wetlands. The latter are closer to the sea level, meaning water that accumulates here also tends to stagnate. The map shows the expansion of built-up area.

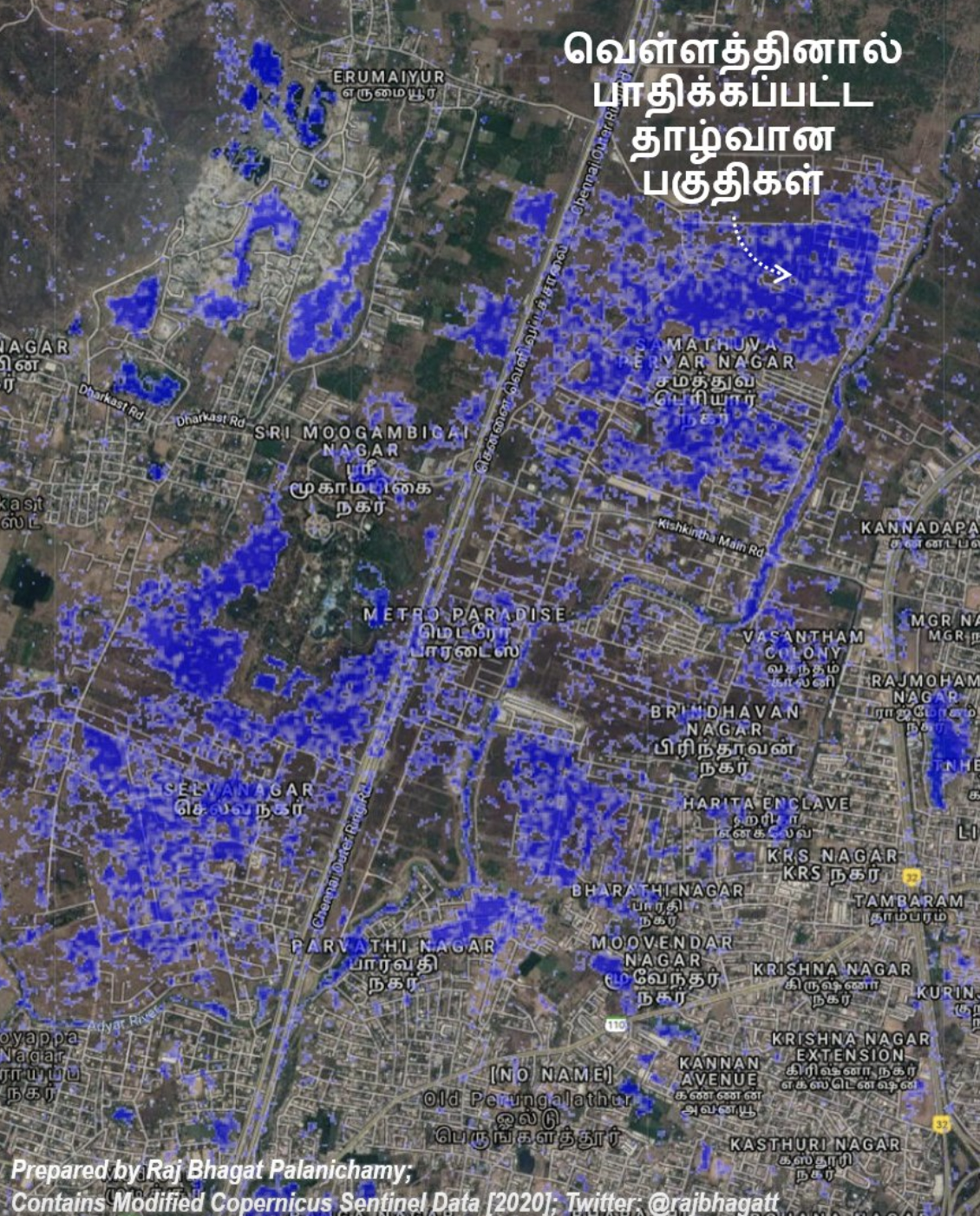

At the same time, even after multiple incidents of flooding, the local government was converting the floodplains of the Adyar river and other streams into urban areas, to accommodate residential, commercial and industrial activities. Today, it would be impossible to vacate many of these premises.

Some of the areas near Adyar river that were flooded in 2020 are shown in this map based on satellite data.

Natural water bodies and wetlands, like the Pallikaranai marsh, can act as buffers, but the Union, state and local governments are not allowing the water to drain anywhere.

The existing built-up area has also rapidly become more dense, which means less water penetrates into the ground as well.

Already existing builtup area have also fast densified over the years which means less water penetrates into ground as well. pic.twitter.com/9fOd24ypjl

— Raj Bhagat P #Mapper4Life (@rajbhagatt) November 7, 2021

Since Chennai has no green infrastructure to help, one would expect artificial infrastructure to step up. However, the designs and construction of the city’s streets and storm-water drains are of really poor quality and they don’t help the city at all.

Any government could also have repurposed and re-engineered the artificial lakes that once served the agricultural lands to serve as buffers. However, many of them have been lost or contain a lot of sewage. As such, they either have a low capacity to act as buffers or their engineering parameters don’t fit the bill. The map below shows the loss of Velachery lake in Chennai as an example.

Neither Chennai city’s master plan nor the city’s disaster management plan address these issues in a scientific manner. The disaster management plan, dated 2017,) has some standard operating procedures. However, they are not rooted in what scientists know about the city’s water resources, and as a result there have been no further detailed, location-specific action plans nor any roadmaps to achieve them.

The solution to Chennai’s urban flooding problem doesn’t lie in the success of technological food management but in better governance. For six years, the city had no mayor or councillors. Unelected officials are unaccountable to the city’s people, and therefore the people’s concerns were unaddressed.

Revamping street designs, scientifically designing and building storm-water drains and maintaining both properly could cost crores of rupees and many years of ground work – even if we start today. But without municipal governance reforms, urban flooding will continue unabated.

This is why Chennai’s flooding issue won’t be solved in the next 10 years. But one also hopes that a long-term roadmap will be drafted – at least today – so that in 10 years, Chennai can be relatively more safe and liveable.

The author of this article originally published its contents as a tweet thread. It has been compiled here with the author’s permission.

Raj Bhagat Palanichamy is a manager of geoanalytics at the World Resources Institute – India. He tweets at @rajbhagatt.