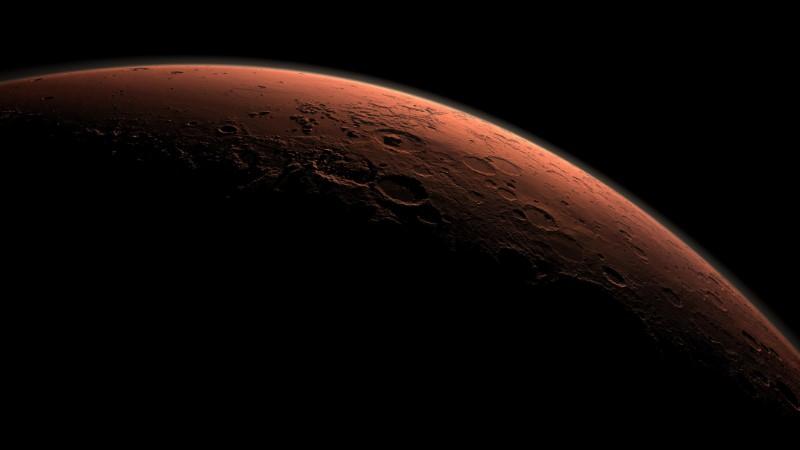

Preparations are already underway for missions that will land humans on Mars in a decade or so. But what would people eat if these missions eventually lead to the permanent colonisation of the red planet?

Once (if) humans do make it to Mars, a major challenge for any colony will be to generate a stable supply of food. The enormous costs of launching and resupplying resources from Earth will make that impractical.

Humans on Mars will need to move away from complete reliance on shipped cargo and achieve a high level of self-sufficient and sustainable agriculture.

The recent discovery of liquid water on Mars – which adds new information to the question of whether we will find life on the planet – does raise the possibility of using such supplies to help grow food.

But water is only one of many things we will need if we’re to grow enough food on Mars.

What sort of food?

Previous work has suggested the use of microbes as a source of food on Mars. The use of hydroponic greenhouses and controlled environmental systems, similar to one being tested onboard the International Space Station to grow crops, is another option.

This month, in the journal Genes, we provide a new perspective based on the use of advanced synthetic biology to improve the potential performance of plant life on Mars.

Synthetic biology is a fast-growing field. It combines principles from engineering, DNA science and computer science (among many other disciplines) to impart new and improved functions to living organisms.

Not only can we read DNA, but we can also design biological systems, test them, and even engineer whole organisms. Yeast is just one example of an industrial workhorse microbe whose whole genome is currently being re-engineered by an international consortium.

The technology has progressed so far that precision genetic engineering and automation can now be merged into automated robotic facilities, known as biofoundries.

These biofoundries can test millions of DNA designs in parallel to find the organisms with the qualities that we are looking for.

Mars: Earth-like but not Earth

Although Mars is the most Earth-like of our neighbouring planets, Mars and Earth differ in many ways.

The gravity on Mars is around a third of that on Earth. Mars receives about half of the sunlight we get on Earth, but much higher levels of harmful ultraviolet (UV) and cosmic rays. The surface temperature of Mars is about -60℃ and it has a thin atmosphere primarily made of carbon dioxide.

Unlike Earth’s soil, which is humid and rich in nutrients and microorganisms that support plant growth, Mars is covered with regolith. This is an arid material that contains perchlorate chemicals that are toxic to humans.

Also – despite the latest sub-surface lake find – water on Mars mostly exists in the form of ice and the low atmospheric pressure of the planet makes liquid water boil at around 5℃.

Plants on Earth have evolved for hundreds of millions of years and are adapted to terrestrial conditions, but they will not grow well on Mars.

This means that substantial resources that would be scarce and priceless for humans on Mars, like liquid water and energy, would need to be allocated to achieve efficient farming by artificially creating optimal plant growth conditions.

Adapting plants to Mars

A more rational alternative is to use synthetic biology to develop crops specifically for Mars. This formidable challenge can be tackled and fast-tracked by building a plant-focused Mars biofoundry.

Such an automated facility would be capable of expediting the engineering of biological designs and testing of their performance under simulated Martian conditions.

With adequate funding and active international collaboration, such an advanced facility could improve many of the traits required for making crops thrive on Mars within a decade.

This includes improving photosynthesis and photoprotection (to help protect plants from sunlight and UV rays), as well as drought and cold tolerance in plants, and engineering high-yield functional crops. We also need to modify microbes to detoxify and improve the Martian soil quality.

These are all challenges that are within the capability of modern synthetic biology.

Benefits for earth

Developing the next generation of crops required for sustaining humans on Mars would also have great benefits for people on Earth.

The growing global population is increasing the demand for food. To meet this demand we must increase agricultural productivity, but we have to do so without negatively impacting our environment.

The best way to achieve these goals would be to improve the crops that are already widely used. Setting up facilities such as the proposed Mars Biofoundry would bring immense benefit to the turnaround time of plant research with implications for food security and environmental protection.

So ultimately, the main beneficiary of efforts to develop crops for Mars would be Earth.

Briardo Llorente, CSIRO Synthetic Biology Future Science Fellow, Macquarie University.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation. You can read the article here.