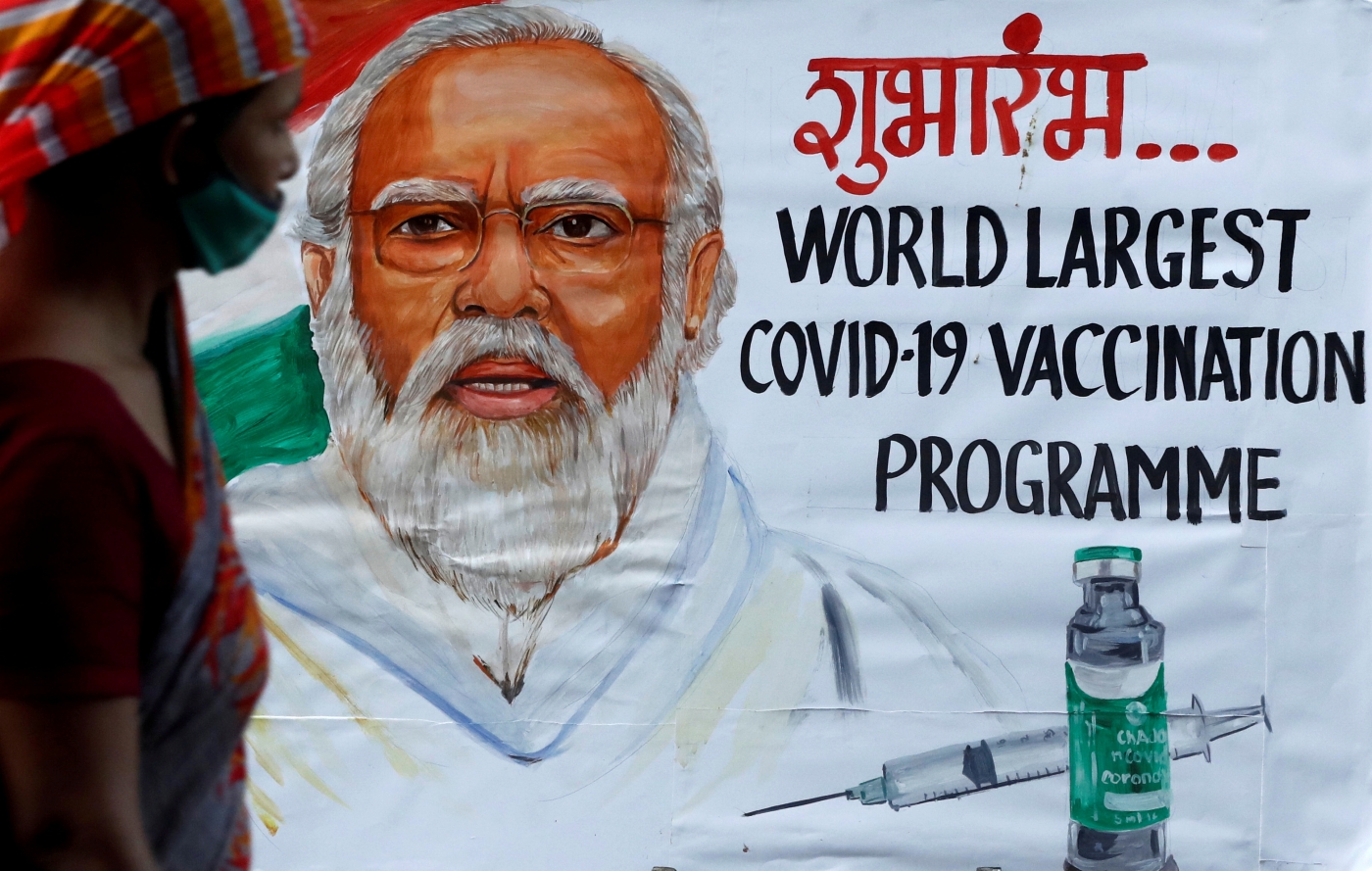

Former Indian health minister Harsh Vardhan holds a dose of Covaxin, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, February 2021. Photo: Reuters/Adnan Abidi

- After the WHO announced its approval for Covaxin, some commentators speculated that Prime Minister Modi’s personal intervention clinched the deal.

- It’s easy to dismiss the speculation as harmless commentary – but not without first considering if it damaged the reputation of Indian science.

- To claim Covaxin’s approval rested on a personal interaction between Prime Minister Modi and the WHO chief is to suggest Covaxin lacked the scientific basis to pass the checks on its own.

As The Wire Science reported yesterday, the WHO’s technical advisory group recommended that the WHO grant an emergency-use listing (EUL) for Covaxin, and which the WHO subsequently did.

Covaxin is the name of the COVID-19 vaccine developed in India by Hyderabad-based pharmaceutical company Bharat Biotech in collaboration with the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). WHO’s official handle also tweeted the news while its director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, tweeted his congratulations.

According to a press release published by Bharat Biotech, the technical advisory group had been considering Covaxin since July this year, after the results of the phase 3 clinical trial became publicly available in June.

The Indian drug regulator, the Drug Controller General of India (DCGI), had granted accelerated and emergency-use approval for Covaxin on January 3, 2021 – despite the absence at the time of any efficacy or long-term safety data. The terms of the seemingly rushed approval also prompted critical comments from independent experts, and raised doubts about the independence and robustness of the regulatory process in India.

In the subsequent months, and after a slow start with some hesitancy among health professionals to accept Covaxin, India’s COVID-19 immunisation drive picked up handsomely – even if it stuttered on other counts. As such, even after administering a billion doses, India has vaccinated only a third of its population thus far, and has missed a deadline to fully vaccinate all frontline workers by three months and counting.

Serum Institute’s Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, called Covishield, has been the mainstay of India’s vaccination drive as a result, with Covaxin playing a relatively minor role in terms of the number of recipients.

Now, what does the WHO listing mean for Covaxin?

It makes no difference for Indians yet to receive a vaccine that Covaxin is the eighth vaccine to be listed by the WHO. It has already been approved for use in India. Instead, the WHO decision is a prerequisite for procurement by international agencies under the COVAX initiative.

So the listing opens the door to Covaxin becoming an internationally used vaccine – subject to production and supply constraints vis-à-vis the company and additional requirements, if any, in other countries.

Indeed, WHO’s listing eases the burden on other countries to grant their own regulatory approvals for the use of Covaxin within their jurisdictions – although not automatic. They are still at liberty to impose their own demands for their green-lights, as the US Food and Drug Administration has done.

Second, travel by Indians who have received both doses of Covaxin will become easier, as more countries will likely accept a certificate of immunisation with Covaxin for entry without the need for quarantine.

Bharat Biotech wrote in its press release that it had ramped up its manufacturing capacity in early 2021 to be able to produce 50-55 million doses a month by October – with plans to reach an “annualised production capacity of 1 billion doses a year” by the end of the year. This is about 80 million doses a month.

Considering the number of production volume deadlines the company has already missed, this assurance may be taken with a pinch of salt.

More importantly, it’s worth considering: did the Prime Minister intervene with the WHO on behalf of Bharat Biotech?

When it comes to muddying the pandemic water, many Indian media organisations are at the forefront – especially when they seek cheap publicity for politicians. For example, three senior journalists of CNN News18 tweeted after the approval came through that it happened thanks to the direct intervention of Prime MInister Narendra Modi, when he met the WHO chief Ghebreyesus on the sidelines of the G20 summit last week.

Using similar language, News18 journalists Marya Shakil, Pallavi Ghosh and Aman Sharma also quoted unnamed ‘sources’ to suggest that Prime Minister Modi had lobbied Ghebreyesus at the G20. Shakil and Sharma also used identical pictures of Modi and the WHO boss in conversation in their tweets.

On the face of it, it seems highly unlikely – almost inconceivable, really – that the PM would have so openly courted Ghebreyesus’s favour to have Covaxin approved. More tellingly, the WHO’s director of communications called Marya Shakil out on Twitter with a less-than-direct denial that the WHO’s technical advisory group arrived at its decision under any external influence.

Hi, @WHO‘s process for assessing #COVID19 vaccines for emergency use listing is rigorous, scientific and standardized. It involves outside experts on a technical advisory group who review data from manufacturers and others to ensure efficacy and safety. Thanks! https://t.co/MgfepF0VRb

— Gabby Stern (@gabbystern) November 3, 2021

It’s easy to dismiss the tweets by the journalists as a harmless bit of speculative commentary – but not without first considering if they were also damaging to the reputation of Indian science.

This possibility arises because, even in the limited context of the COVID-19 pandemic, India’s scientific enterprise has been repeatedly undermined by a flawed, opaque and weak regulation apparatus.

This happened in pronounced fashion on two occasions recently – when the DCGI approved Covaxin’s emergency use in “clinical trial mode”, and when the People’s Hospital scandal in Bhopal came to light.

The DCGI’s decision came at a time when Covaxin’s phase 3 clinical trial had just begun, and about a couple months after Prime Minister Modi had visited the manufacturing facilities of Covaxin and Covishield.

This is to say that Covaxin already suffered once the dubious success that comes with the combination of the promise of good science and extra-scientific patronage – versus good science, period. Covaxin’s maker Bharat Biotech didn’t do a good job of projecting, and then preparing for, India’s vaccine demand in early 2021, but that’s not the only reason Covaxin makes up just a little over 10% of all doses administered.

It is dubious because it has little to do with science, just like claiming Prime Minister Modi was instrumental in securing Covaxin’s approval with the WHO takes the whole effort away from scientists.

The People’s Hospital incident provoked a similar message – this time from Bharat Biotech. In January 2021, it came to light that hospital staff had manipulated poor, illiterate people in the same neighbourhood into participating in Covaxin’s phase 3 trial at the site. But when the Bharat Biotech researchers who administered the trial uploaded their preprint paper in July, they didn’t mention the People’s Hospital incident or the specific ways in which ethical lapses at this trial site compromised (or didn’t) the findings – which wouldn’t have been hard to do.

So to claim that Covaxin’s approval rested on a direct personal interaction between the prime minister of India and the head of the WHO is to suggest that Covaxin lacked the scientific basis to pass the checking process on its own, that it required the patronage of the most powerful person in the country.

There is every reason to believe that the WHO’s technical advisory group is independent – so by casting doubt on its independence with no firm basis, we will only undercut the hard work of India’s scientists and trial participants (including the already at-risk dignity of the people wronged by the People’s Hospital fiasco).

There is no argument that experts working for the manufacturer or the regulator must never fall below the standards expected of them. And when they do, journalists must expose the resulting malpractice with evidence, like this report by a US Congressional oversight group vis-à-vis the FDA.

As such, speculative commentary in this context, and at this juncture, is in poor taste and quite frankly sycophantic. Perhaps it will always be Covaxin’s legacy that, among other things, it will constantly pit India’s political clout in the international arena and scientific accomplishment within the country against each other.

But instead of accepting this opposition in uncritical fashion, the rest of us must navigate it such that we don’t further tarnish the reputation of the latter.

Dr Jammi Nagaraj Rao is a public health physician, independent researcher and epidemiologist in the UK.

This work by The Wire Science is licensed under CC BY-ND 4.0