A laboratory technician prepares a sample for an RT-PCR test at a facility in Seibersdorf, Austria, May 2020. Photo: iaea_imagebank/Flickr, CC BY 2.0

Note: This article was first published on June 20 and was republished on June 22, 2021.

Hyderabad: After a sluggish testing response to the pandemic in early 2020, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) decided to tap India’s private sector. The ministry put the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) in charge of approving private laboratories that could offer tests.

ICMR is generally responsible for coordinating and promoting biomedical research in India, and had no experience with approving testing labs. So instead of conducting an audit of its own, it borrowed the expertise of the National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories (NABL) – a self-financed body “established with the objective of providing government, industry associations and industry in general” with accreditation.

Specifically, ICMR asked interested parties to fill a form with details of whether their facilities had instruments that could perform RT-PCR tests, the number of sample collection sites and if the lab had been accredited by the NABL or any other bodies.

After getting this information, ICMR appears to have approved those labs that reported having NABL accreditation.

“To attain COVID-19 testing approval by ICMR, the capability of the laboratory is to be ascertained, and thus NABL accreditation is required as a prerequisite,” NABL CEO N. Venkateswaran told The Wire Science.

This strategy sent many labs interested in performing COVID-19 tests rushing for the NABL’s seal as well. This was to be expected: according to one estimate, India’s COVID-19 testing market is worth Rs 7,300 crore.

The Department of Science and Technology founded the NABL in 1988. It provides voluntary accreditation services to testing and calibration facilities in line with ISO standards.

The test of choice to check for COVID-19 is the reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The NABL considers it under a category called “molecular testing”.

Every year, the NABL also publishes a list of labs whose accreditation is active. According to the 2019 edition, the accreditation statuses of 1,170 labs were ‘active’ in the ‘medical testing’ category, with only 12 labs engaged in ‘molecular testing’. But between October 2019 and May 31, 2021, there were 2,065 accredited labs, with over 1,200 engaged in ‘molecular testing’.

Accreditation process

Accreditation used to be a longer process, involving the preparation of several documents, manuals and standard operating procedures (SOPs) to ensure the quality of tests in a lab, and a pre-assessment and a final assessment involving a two-day on-site audit.

But for COVID-19, the NABL shrunk this into a five-hour audit. The Wire Science spoke to an active NABL assessor with extensive auditing experience at the national and international levels. “Since COVID-19 testing involves auditing the quality control process of one only test, i.e. the RT-PCR, the audit time was shrunk,” the assessor said on condition of anonymity. “During the audit, the applicant lab demonstrates its ability to conduct this test and then accreditation is granted.”

“The NABL by itself does not have any technical staff to conduct any audits. They rely on experts who work in the area to conduct these audits objectively,” the assessor added.

The NABL has also been conducting audits remotely, through video-calls, since the pandemic began, according to the assessor and personnel at some labs.

According to an NABL document (no. 112) entitled ‘Specific Criteria for Accreditation of Medical Laboratories’, its accreditation is granted for tests at a particular site. So a company operating a chain of labs in the country has to have each lab accredited separately.

“We are considered a small lab as per NABL criteria, but the accreditation process is expensive,” a member of the managerial staff of one such chain in Mumbai said. “NABL charges fees for their assessments. We pay an honorarium to the assessors at NABL-decided rates, and their accreditation fees – sort of an annual fee to be paid every year.”

The manager said this particular chain has spent around Rs 1.5 lakh per site for the certificates.

The NABL is usually a stickler for details, and some tests also warrant nuanced scrutiny. For example, the performance of some tests can vary according to the type of sample available to test. DNA is present in most cell types in the human body, but extracting sufficient amounts of it to test is easier to do from blood than from hair. Tests have been known to fail for lack of sufficient DNA.

Such exactitude inspires confidence. But during the pandemic, the NABL seems to have slipped, as its own certification reveals. And when the ICMR depended on the NABL to do due diligence, it inherited the accreditation agency’s alleged slip-ups as well.

Lenience

The scope of accreditation for all NABL-accredited laboratories is in the public domain. The Wire Science accessed this information for COVID-19 testing labs, along with information about the sample type for which the accreditation was granted.

For most labs, the NABL had audited tests having to do with detecting an RNA virus in the blood. Here are a few examples of labs that feature on ICMR’s approved list and the scope of their NABL accreditation.

The second column refers to the sample type – and for the four tests cleared for accreditation above, it doesn’t mention swabbing, which is how samples for RT-PCR tests are collected. A laboratory chain in Bengaluru (see below) has been accredited for the correct sample type, in contrast.

When asked, Venkateswaran didn’t explain how accreditation was granted sans swabbing.

A test’s performance can vary by sample type. “Detecting a virus from a nose swab is much more of a challenge than from a blood sample,” an application specialist in Hyderabad, with an international provider of COVID-19 test-kits, said, on condition of anonymity as he did not have permission to speak to the media.)

“There are multiple variables – the way the sample is collected, the kit used to extract RNA, the detection limit of the RT-PCR kit used – and all of these can impact the test result. It is easy for a person to test negative if any of the preceding steps is done incorrectly.”

“It is strange that a body like the NABL has allowed such a large deviation,” the NABL assessor said. “In my experience, this is the first time the NABL has been so lenient in the accreditation process.”

During its audit, the NABL also seeks details of individuals who will perform the tests at each lab and of those tasked with releasing the final report. Assessors also vet the technical qualifications and competence of all authorised signatories.

When an authorised signatory is not available to review test results, the NABL guidelines insist that an “interim” report must be released so that patient management isn’t affected.

However, some large diagnostics chains seem to have the same personnel signing off on reports at multiple test locations. The NABL assessor said the body’s guidelines don’t say this is a problem: “I cannot reject an authorised signatory if she signs reports in one suburb in the morning and another suburb in the evening. She is well within her rights to work at multiple locations.”

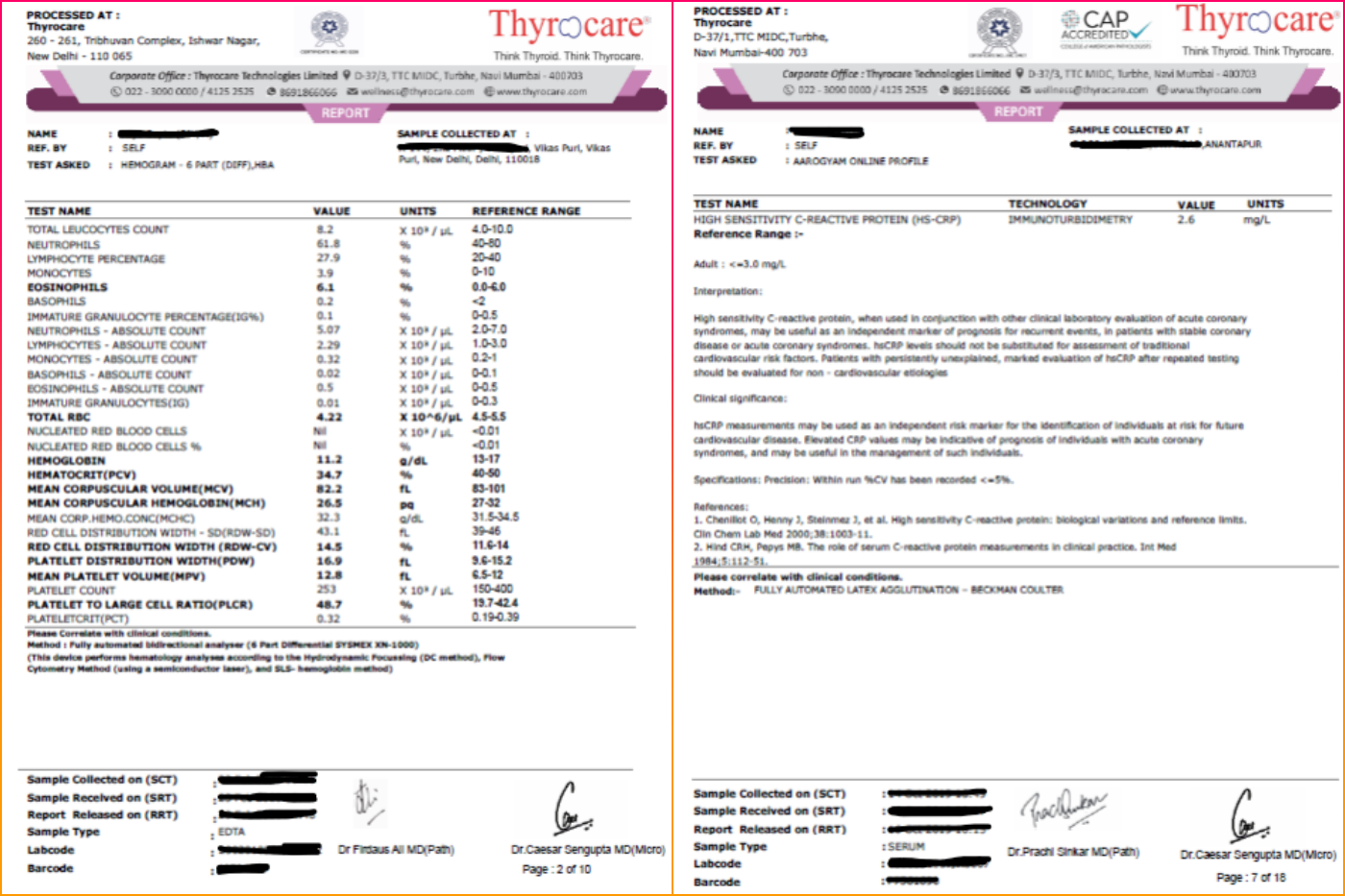

However, what of instances in which the same person signs off on reports generated in different cities? This is the case with Thyrocare, for example. The Wire Science was able to access copies of some reports from its labs in New Delhi and Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh.

At the time of publishing, Thyrocare hadn’t replied to an email requesting their comment.

“At times, the test values can exceed normal limits because the sample has not been collected properly or has deteriorated,” a senior pathologist in eastern India told The Wire Science. “It is the duty of the signing authority to verify the sample, its condition and release the report only after ensuring that the sample integrity has not been disturbed. If there are any doubts, the test must be repeated or even a fresh sample requested.”

The NABL guidelines are also flexible about allowing laboratories to automate their reporting. However, the NABL assessor said there isn’t a single lab in India “that uses such sophisticated software that can take into account so many variables and decide whether to release a report.”

“During the assessment, we ensure that at least one dedicated person is available to report, review and authorise the results,” Venkateswaran said. “There can be additional resources who can be operating from different places.”

Finally, for medical tests, the Medical Council of India was quoted by the Times of India as saying in December 2019 that digital signatures and remote authorisations are invalid, and that a doctor must be physically present to validate all lab reports.

The NABL’s position on this matter is less well-defined, although it is at odds with the MCI’s. In case of a conflict with existing regulations, the NABL guidelines (no. 112) simply say that local, regional and national laws will take precedence.

“NABL has no statutory powers. Checking of compliance to the regulatory requirements falls under the purview of the respective regulator,” Venkateswaran said.

Omnipresence

Every quality management system in all laboratories has to have a quality manager tasked with overseeing customer complaints, reviewing contracts, evaluating and selecting suppliers and ensuring day-to-day activities happen according to predetermined protocols. This person should also conduct internal audits across various departments and ensure the labs document their activities properly.

In a complaint dated May 23, 2021, Dr Rohit Jain, a pathologist in Jaipur and founding-secretary of the Practicing Pathologists’ Society, Rajasthan, brought an issue with two lab chains to the NABL’s notice.

The labs, Dr Jain wrote, appeared to have appointed the same quality manager at multiple sites. Medall had the manager working at 12 locations (some 1,200 km apart) while Krsnaa Diagnostics had split one manager up across eight locations. In both cases, all sites had NABL accreditation.

The Wire Science was able to confirm Dr Jain’s concerns through an NABL document (no. 600) that lists all accredited labs in the country.

The NABL has yet to acknowledge his email, Dr Jain said on June 8. Emails to Krsnaa and Medall hadn’t elicited replies at the time of publishing.

In an email to The Wire Science on June 15, NABL CEO Venkateswaran said, “The query is resolved now. Every lab [at each location] will have a person to ensure quality of operations. They can be a deputy to the central quality manager for uniformity in group organisations.”

However, he didn’t say how the issue could have cropped up in the first place – or if the NABL had verified the ‘resolution’ directly instead of taking the labs’ words for it.

Testing proficiency

The NABL also has a proficiency-testing (PT) accreditation programme. Currently, the NABL lists 49 labs that are accredited PT providers, nine of which provide material for medical testing. (The other 40 are concerned with other forms of testing, like electrical, chemical, mechanical, etc.)

These labs send PT material, in the form of samples, to other labs at different points through the year. The receiving labs test the samples and report their findings, along with the findings of tests performed in the course of their operations.

The PT lab then compares the results with their own, and responds with a report describing what the participating lab got right, wrong, etc.

The PT provider has its own testing criteria depending on the samples it sends out. Biochemistry samples are typically issued on a monthly or quarterly basis, and their tests are assessed quantitatively. The samples for COVID-19 tests are qualitative: the PT provider only needs to know if the recipient lab found a sample ‘positive’ or ‘negative’.

If a lab tests most samples correctly, it is certified by the PT provider for that test.

This way, the NABL’s quality-control programme is a goldmine of data about the performance of different testing kits, variability in testing between different labs and the accuracy of tests at a given site. Or at least it ought to be.

No lab has stepped up to do PT work for COVID-19 tests. Instead, to this end, the ICMR runs the Inter-Laboratory Quality Control (ILQC) programme. It has appointed 38 labs across India – premier government medical colleges in the state, ICMR labs or regional AIIMS hospitals – to dispatch PT materials to participating labs and collect data on their performance.

However, none of the nine NABL-accredited medical PT providers feature on ICMR’s list.

According to Venkateswaran, ICMR “conducting the program is a welcome step and gives additional confidence for approving labs” – but he refused to say anything more on the ICMR programme’s specifics.

In addition, apart from the list of participating labs that ICMR released in January 2021, it has not shared any other details of the ILQC programme. The Wire Science contacted ICMR requesting more information but hasn’t received a reply.

“We receive PT material from the state quality-control lab,” the quality manager with a COVID-19 testing chain in Mumbai said. “Earlier, we had to report the Ct values for the samples tested, and the margin of error was two cycles.”

‘Ct’ stands for cycle threshold. Each RT-PCR test runs through a series of cycles, each of which amplifies the presence of a certain genetic material in the sample. The cycle threshold is the number of cycles after which the test can be said to be positive. If the viral load in a given sample is high, the Ct value will be low.

“For the last few months, we have just had to report if a sample is positive or negative; no Ct value is required,” the manager said. “We don’t even mention which kit was used for the analysis. We receive a consolidated report if our results matched, but individually, we don’t know which or how many samples failed.”

The NABL assessor said, “This data is like a performance tracker that should be out in the public domain.” It isn’t.

Not so optional

Falsely negative COVID-19 test results could leave actually infected individuals complacent, allowing the virus to spread further, or deny people crucial medical care.

In May 2021, a lab in New Delhi bungled the test results of a group of Australians, causing them to miss their repatriation flight back to their home country. It soon came to light that the facility had continued to provide testing services despite having lost its NABL accreditation a month earlier.

Venkateswaran said, “Generally, the [suspended] lab is required to inform [the regulator] as per procedure. We have now introduced a system of updating the regulator directly.”

Publicly as well as in communications with The Wire Science, Venkateswaran repeatedly said, “NABL accreditation is voluntary. NABL does not force laboratories to obtain accreditation and cannot instruct the lab not to do testing.”

This is true – but only on paper. Of late, NABL accreditation has become too important for India’s diagnostic facilities to overlook.

ICMR’s strategy to approve only those labs with a NABL-accreditation for COVID-19 tests is one example. For another: a MoHFW notification issued last year specified the rates for 25 tests at NABL-accredited labs – and said non-NABL labs would have to charge 15% less.

In yet another instance, in 2018, the Himachal Pradesh government issued an e-tender for lab services in government health institutions, and said non-NABL labs wouldn’t be eligible.

But, the senior pathologist said, “having a NABL certificate does not give you the true picture. A lab can be accredited on only a few parameters and still produce a NABL certificate and charge extra for all parameters, irrespective of the quality of testing.”

In his email, Venkateswaran only said, “A lab can decide to apply for [limited] scope or full scope for accreditation purposes. The entire lab need not get covered under accreditation.” But this is the impression many labs have been giving.

“The biggest misnomer in all this is the ‘NABL-accredited laboratory’,” the pathologist said. “The accreditation is for some tests specified in the annexure and not for the lab as a whole. Labs know this, but continue to misuse the accreditation because it suits them.”

“Nobody in the NABL wants to take responsibility” for these shortcomings, the NABL assessor added. “They have made a complete mess of quality control in India.”

Ameya Paleja is a freelance writer based in Hyderabad. He blogs at Coffee Table Science.