File photo of a sterilisation camp for women. Photo: Reuters

- India has adopted the “cafeteria approach” for its family welfare programme, in which couples have multiple options to choose from depending on their needs.

- This policy has been truer on paper than on the ground, where policy design often overlooks the socio-cultural context in which ‘street-level bureaucrats’ operate.

- Based on conversations with ASHA workers, the authors discuss some of the ways in which decisions become biased towards female, over male, sterilisation.

According to recent estimates from the fifth National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), the use of family planning methods in India increased from 53.5% in 2015-2016 to 66.7% in 2019-2020. An increase of 25% in five years on this count is remarkable.

Access to family planning methods, or contraception, helps reduce maternal and infant mortality by ensuring adequate spacing between births, freedom from unintended pregnancies and lower chances of pregnancy complications. The outcome measure for the success of this programme is considered to be the total fertility rate (TFR).

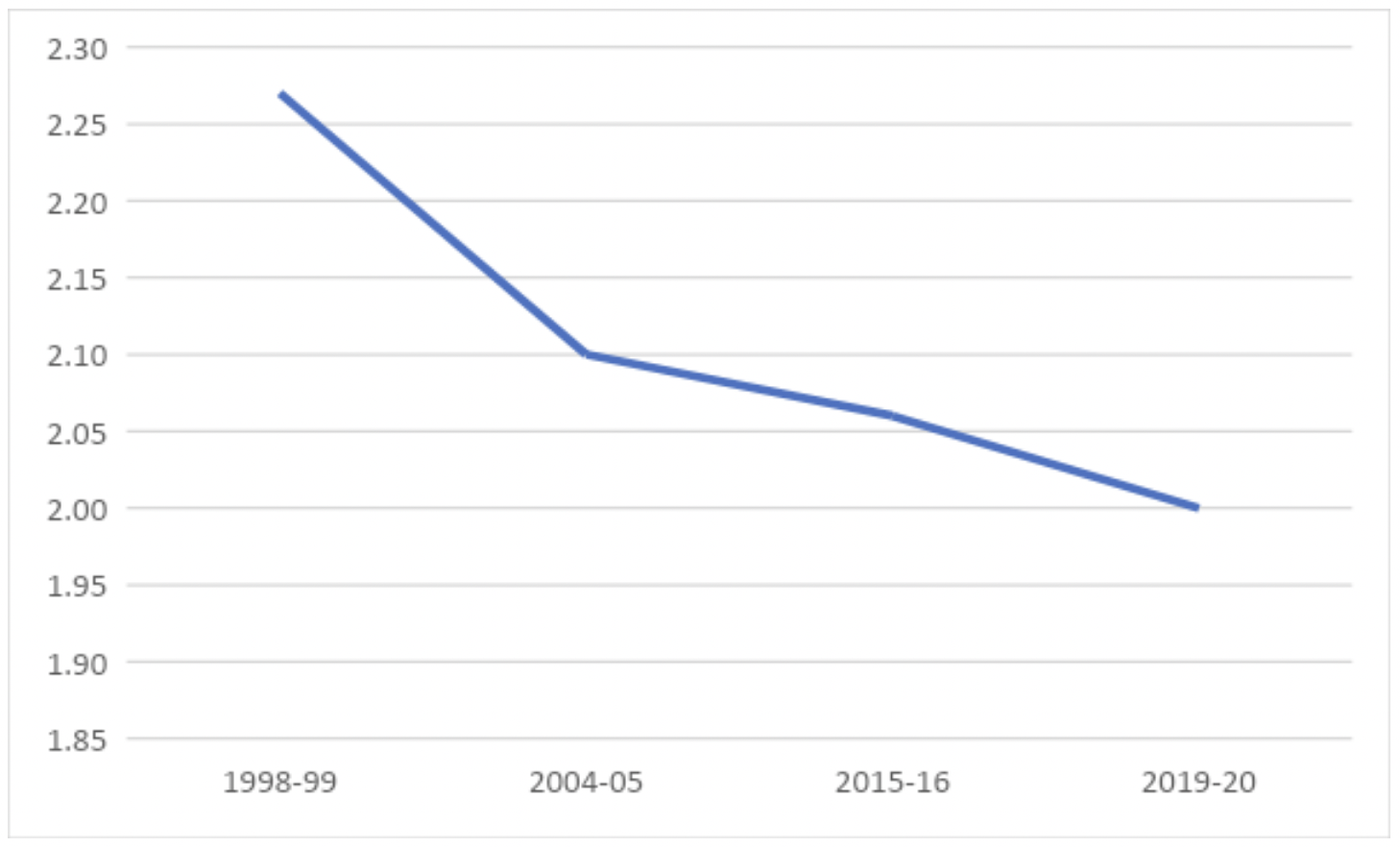

Figure 1 depicts a TFR trend declining steeply from 1998-1999 to 2019-2020, which is desirable from the population control point of view. But are we on the right path?

India has adopted the “cafeteria approach” for its family welfare programme, in which couples have multiple options to choose from depending on their needs and requirements – at least on paper.

‘Family planning’ ideally implies informed and voluntary decisions of individuals to manage their family size according to their preferences and the resources at their disposal. However, the terms ‘family planning’ and ‘female sterilisation’ are often used interchangeably – which in itself ridicules the concept of choice as it pertains to women.

In addition, a break-up of the use of different methods of family planning shows that female sterilisation remains the most common method of contraception: 38% of women aged 15-49 years reported using this method in NFHS-5.

Female sterilisation is a permanent method of contraception. One 2003 study that analysed patterns in the use of this method found that half of India’s women were sterilised by the age of 35 years and that most of them were sterilised between the ages of 20 and 35. One reason for this was “unwillingness of men to use any method”, especially men belonging to lower socio-economic strata. This forces women to opt for permanent sterilisation.

Studies have also linked sterilisation to the risk of menstrual dysfunction later in life. So in the basket of all choices, female sterilisation may not be the best one. However, policymakers have considered India to have had access to just such a ‘basket’, in the ‘cafeteria approach’, since the 1980s.

Policy outcomes are guided by policy design elements and effective implementation. The effectiveness of implementation depends largely on ‘street-level bureaucrats’ – officials who mediate the relationship between the state and citizens.

Michael Lipsky introduced the term ‘street-level bureaucrats’ in 1980 to refer to frontline public workers who interact directly with the people, and who often enjoy a substantial level of discretion in the execution of their functions.

Now, given one of the main tasks of the Accredited Social Health Activists, a.k.a. ASHA workers, under the ‘Reproductive Child Health’ programme, is to provide family-planning counselling, we can safely assume that they also implement the ‘cafeteria’ approach.

We argue here that implementing the ‘cafeteria approach’ in a way that is true to its spirit depends largely on the attitude, behaviour and discretionary power of family planning counsellors and advocates on the ground – which are ASHA workers and auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs). Our arguments here are drawn from conversations with ASHA workers in Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat.

Also read:

Context of decisions

India was the world’s first country to launch a family planning programme, in 1952. Over the last six or so decades, this programme has evolved in its approach and design. It launched as a clinical programme and was soon replaced by a focus on community education and promoting small-family norms. Then, for a brief period of two years in the early 1970s, the government adopted a coercive approach, and was criticised for it.

In 1977, the government renamed the programme to focus on family welfare and adopted the ‘cafeteria approach’ was followed. Couples were given multiple choices: female sterilisation, male sterilisation, intrauterine contraceptive devices, oral contraceptives and condoms. This programme was also integrated with the ‘Reproductive and Child Health’ programme.

The government’s efforts vis-à-vis birth control have been commendable but at the same time they seem to ignore the socio-cultural contexts in play when couples decide which method to adopt and when. Family planning counsellors, ASHA workers and ANMs are mostly women, and thus typically target other women as part of their work.

According to NFHS-4 data, three in eight men believe contraception is a woman’s business; perhaps this is why only 0.3% of couples in India have opted for male sterilisation. Some ASHA workers in Haryana also told us that they believe female sterilisation to be the best option – especially after the birth of a male child – because it’s a one-time event that precludes the need to visit health centres again and again and because the government incentivises it.

Some ASHA workers also said, “We distribute condoms to women in the community but these women are powerless and fail to convince their husbands, and then we have to manage their unwanted pregnancies, that too in a secretive manner.”

The contexts in which ‘street-level bureaucrats’ operate is an important factor that influences the implementation of policies. Their own choices, their understanding of the better contraceptives methods and the prevailing gender and social norms affect their ability to disseminate information in a target group. At the simplest, they tend to affect women’s decisions by emphasising those methods that they consider better or more appropriate.

ASHA workers are usually part of the same community of people that they’re working with, and for them to truly implement the ‘cafeteria approach’, they will need to understand the importance of presenting the women they engage with different choices, to be aware of the short- and long-term implications of different choices, and to involve the men of each family in their conversations.

Vanita Singh is an assistant professor of public policy at the Vijay Patil School of Management, D.Y. Patil University, Navi Mumbai. Shobha Kumari and Pratima are pursuing a masters in public health at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai.