She is the author of My Husband and Other Animals.…

Humming males are like beacons to egg-heavy females. But for some reason, some males don’t hum.

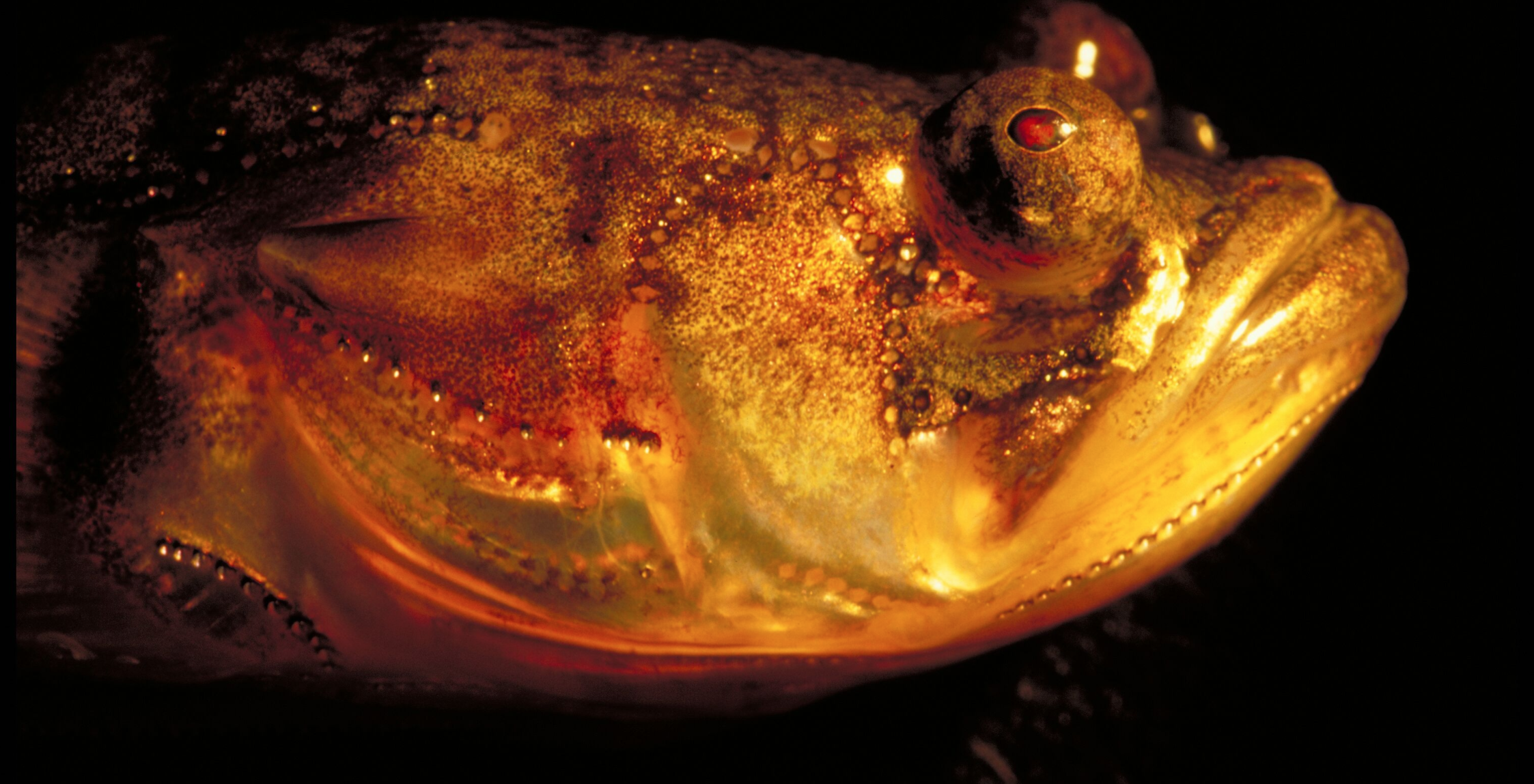

Fish are not silent. At least a thousand species pop, whistle, and growl underwater. Male midshipman fish hum so females can locate them. Scientists reveal what makes them call.

In spring, male midshipman fish drone from nests they make under rocks close to shore. When scores of these foot-long fish call in unison, their chorus reverberates across harbours. Some compared the din that can last for hours to foghorns, oboes, motorboats and guitar amplifiers. In the past, residents of California and Seattle in the US, and Southampton, UK, were perplexed by the booming call. They suspected noisy sewage pumps, military testing and even extraterrestrials were the cause. In one case, sleepless residents even sold their property and moved away.

Vocal cords play no role in the midshipman’s humming sessions. Instead, the fish contract special sonic muscles that vibrate against their swim bladders, a gas-filled sac to keep them buoyant. These droning singers attract groupies, female midshipman fish full of eggs.

Researchers found songbirds sing during the day when melatonin levels are low. Melatonin is the time-keeping hormone that controls cycles of sleep and wakefulness. The pineal gland produces it at night. It stimulates sleep in diurnal creatures and wakes up nocturnal ones. Human activities are also dictated by the hormone. At dusk, when melatonin levels start increasing, daytime birds fall silent. But they can’t stop singing in a lab where the lights are left on at night. What’s the role of the hormone in making nocturnal fish like midshipman drone?

Professor Andrew Bass of the Department of Neurobiology and Behaviour at Cornell University and his doctoral student Ni Feng collected male midshipman fish off the coast of Washington State and California, US, and shipped them east to New York. In the lab, automated lighting provided the study’s subjects with 15 hours of daylight and nine hours of dark, a typical summer routine in those northern parts. When it grew dark, the fish hummed.

“We were happy that the wild-caught fish hummed on a regular basis in our laboratory aquarium setup,” Ni Feng told The Wire, “which meant we could begin to record from them and manipulate the room lighting to see the effects on their vocal behaviour.”

When the experimenters shifted the light regime to 24 hours of night, the fish kept to their schedule: booming and silence. Their internal clock seemed to tell them when to call and when to shut up.

In the next stage of the experiment, Feng and Bass kept the light switch on for 24 hours. Light suppresses the secretion of melatonin. On the first day of constant light, they implanted six fish with artificial melatonin, six with just coconut oil and two got neither. If melatonin made fish drone, 24-hour daylight would inhibit midshipman implanted with coconut oil and the ones that got nothing at all. But the artificial melatonin boost would make the fish hum even though the lights were on all the time.

When they performed the experiment, the fish behaved just as they expected. This, the authors of the paper say, proves that melatonin controls the humming activity of male midshipman. In fact, the melatonin-implanted fish hummed even more than before.

In sharp contrast, owls function because they produce hardly any melatonin. Their pineal glands are smaller and produce little melatonin. This allows the birds to hunt and call at night. We know little about how melatonin works in other nocturnal creatures.

But not all male midshipman hummed in the lab, not even under natural light regimes. Implanting these non-hummers with melatonin didn’t persuade them to start making a racket. Humming males are like beacons to egg-heavy females. So why don’t some males hum?

There could be several reasons. One, male midshipman come in two types. Type I males hum to seduce the ladies. Type II males are small and silent and thus have a different strategy. When females spawn inside nests made by their Type I beaus, the Type II chaps masquerading as females sneak in and fertilise the eggs without raising an alarm. But the experimenters chose Type I males for the experiment.

“It is impossible to replicate everything about a wild environment in the laboratory,” says Feng. “Although many fish felt right at home in our aquarium setting, others may have preferred their natural homes to express their courtship behaviours.” It’s also likely they didn’t have enough fishy testosterone coursing through their blood.

Besides these behavioural experiments, the researchers studied the expression of melatonin receptors in the fish’s brain. The only melatonin receptor in songbirds is Mel1b. Feng and Bass found it in parts of the midshipman brain that control vocal, social, and reproductive behaviours.

The researchers plan to continue exploring this subject further. “We’d like to know if the melatonin receptors change their levels across the day in specific brain regions controlling the midshipman’s vocal behaviour,” says Feng. “A more challenging question is whether melatonin also stimulates the vocal behaviour of other nocturnal species, like many frogs and even birds like nightingales. Finally, it will be interesting to look at the molecular pathways that help to interpret the nocturnal melatonin message in opposing ways in nocturnal vs diurnal species.”

Bass has researched what influences the chorus for several years. About a decade ago, he suggested high levels of the fish version of the sex hormones, androgen and oestrogen, in the blood of Gulf toadfish make these fish call. Are midshipman and toadfish driven by different hormones? How does the latest research proving melatonin’s role explain this?

“Our lab has shown that hummers have higher levels of 11-ketotestosterone [a testosterone-like hormone],” says Feng. “We think steroid hormones can activate the behaviour, but melatonin provides timing information about when it’s best to hum. As an analogy, I think of melatonin as the green light that provides a ‘go’ signal, but steroid hormones as pushing on the gas pedal to get the humming behaviour actually going.”

Professor Bass says there might be a difference in the role of steroids between species. The call of toadfish is called boatwhistle. Males that boatwhistle have higher levels of cortisol, a glucocorticoid, than the silent ones. However, in midshipman, cortisol has the opposite effect: the silent type has higher cortisol levels.

There was another key difference between the two studies and species, says Professor Bass. Humming male midshipman that tested high on 11-ketotestosterone and testosterone levels had no singing companions. They droned all by themselves. But in the toadfish study, the males boatwhistled with other males. They could hear and respond to each other.

To cope with the din, male midshipman fish become slightly deaf by stiffening the cells of their inner ears. It would defeat its purpose if females were able to turn off the long monologues. The silent, small males have to put up with the racket too. If they didn’t turn down the volume, how do they cope?

“While male midshipman become less sensitive to their own “voices” when they are making sounds, they may still retain the ability to hear both their neighbours’ sounds and their own sounds,” Professor Bass told The Wire. “This is a very exciting question we hope to be able to answer in the future.”

The study was published in the journal Current Biology on September 22, 2016.

Janaki Lenin is the author of My Husband and Other Animals. She lives in a forest with snake-man Rom Whitaker and tweets at @janakilenin.