Photo: Reuters/Dado Ruvic/Illustration/File Photo.

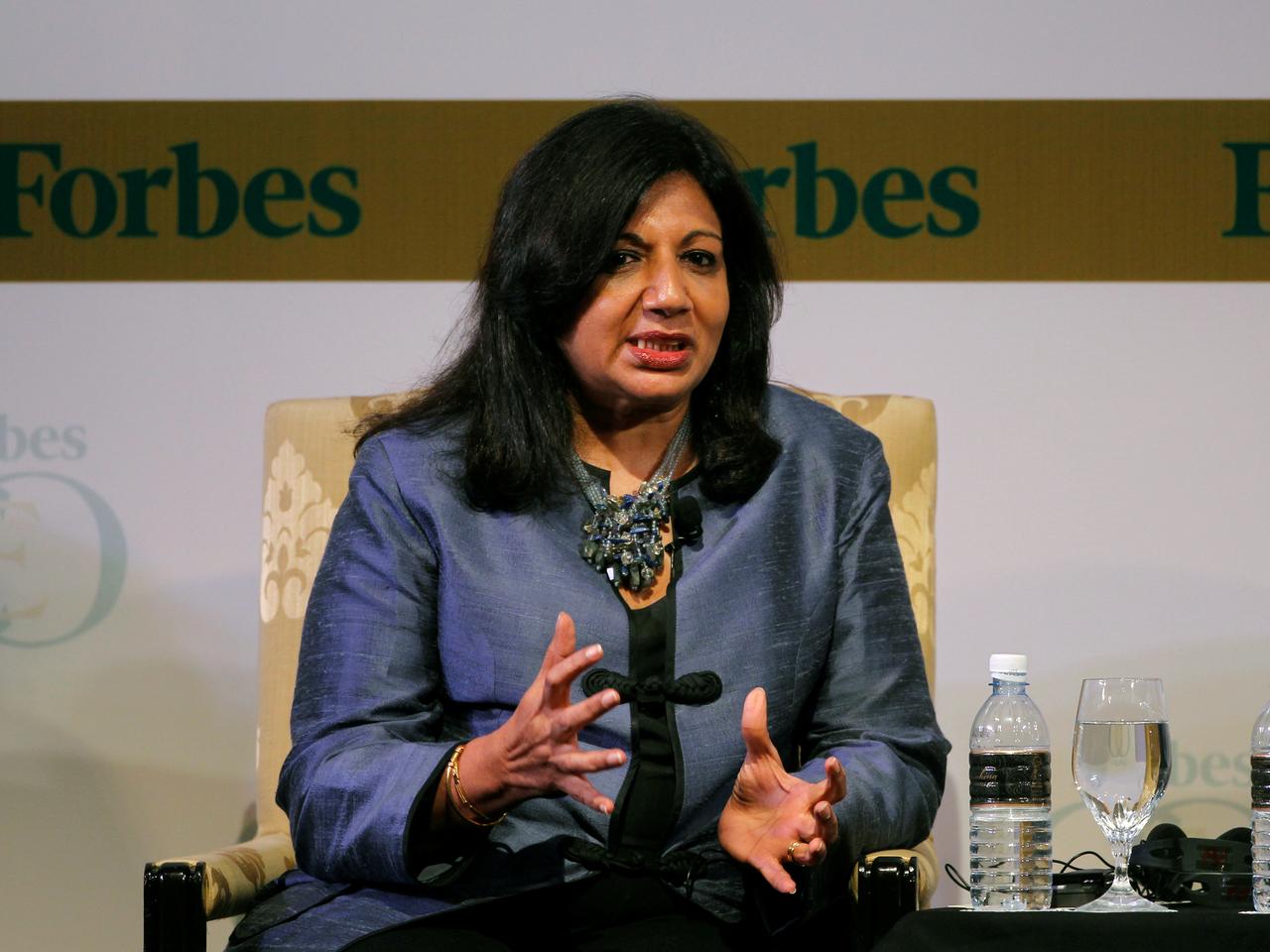

Bengaluru: More than a month after the Indian drug regulator’s controversial approval of Biocon’s drug Itolizumab, new documents and the company’s own admissions raise serious doubts about the quality of the clinical trial Biocon conducted.

Based on this trial, which enrolled only 30 patients, the Central Drug Standards and Control Organisation (CDSCO) had on July 12 approved the use of Itolizumab in COVID-19 patients.

Now, worrying discrepancies have emerged between the claims made by Biocon’s chief medical officer Sandeep Athalye at a press conference on July 13 and how the trial was actually conducted. For example, even though Athalye said the trial had randomised 30 patients, five of these patients had actually not been randomised. And trial investigators didn’t record this fact on the Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI) website either.

Second, Athalye had said that the trial followed a commonly used design for emergency-use drug trials, called the Simon two-stage, which allows investigators to determine efficacy based on small sample sizes. But other experts pointed out that this design applies only to single-arm trials, while the Biocon Itolizumab trial had two arms.

“This is crazy. Anyone who understands the basics of a Simon two-stage knows that this is not a Simon two-stage,” C.S. Pramesh, director of the Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, who has conducted trials for cancer therapies that rely on this design, told The Wire Science.

The discrepancies don’t end here. A document published on Biocon’s website, which Siddhartha Das, a postdoc at the Université Libre de Bruxelles tweeted on August 23, suggests several other statements by Athalye at the press conference didn’t reveal the full picture of the trial.

The fourth slide of Athalye’s presentation notes that two of the patients who were randomised had dropped out of the trial before receiving their first dose. In contrast, the fourth slide in the document on Biocon’s website, which mirrors Athalye’s presentation on July 13, says two patients who dropped out had received their first doses of Itolizumab and suffered an adverse event called an infusion reaction. While one of the two patients recovered, the other died of COVID-19 nine days after dropping out.

Asked about these discrepancies, Seema Ahuja, the company’s global communications head, confirmed the authenticity of the second document. However, she said the differences between the two documents had arisen because the second document showed “reconciled” data that the company had collected from its trial sites.

“This is the final summary post reconciliation,” Ahuja wrote in a WhatsApp message. “The reconciliation process involves going back to source data at all sites and revalidating.” However, she didn’t answer a question about when the so-called reconciliation occurred and why Athalye’s presentation didn’t reflect it.

Several experts The Wire Science spoke to said these mismatches indicate a badly done trial and possibly an intention to mislead listeners at the press conference. According to Jammi Nagaraj Rao, an epidemiologist in the UK, while the discrepancies suggest poor control of the trial process, “not mentioning the two patients who were taken out of the study because of a reaction, and that one of them died, is definitely at least misleading and sharp practice.”

What Biocon didn’t say

During its May 28 meeting, a subject expert committee (SEC) of the CDSCO, a body that must approve all changes to protocols for regulatory clinical trials, made two observations about the Itolizumab trial, which had reached its mid-point then. The SEC said the company hadn’t randomised the participants in its trial properly, and that Itolizumab couldn’t be given emergency approval at that stage, because the trial’s investigators were attempting to conduct an interim analysis that they hadn’t planned for before the trial began.

Athalye told The Wire Science that the SEC’s statement referred to investigators changing the trial protocol early on. While the initial plan was to randomise 30 patients, he said, there were concerns that these patients, who were severely ill and vulnerable, may suffer adverse effects.

“We had no idea what Itolizumab’s safety is like in these patients,” he said. So the trial’s Drug and Safety Monitoring Board, a panel of independent experts that monitors the trial, suggested Itolizumab first be given to five patients in a staggered manner, so that investigators would have time to respond to adverse events.

Following this recommendation, Athalye said, the first five of the 30 randomised patients had been given Itolizumab sequentially. Subsequently, he continued, the remaining 25 were randomised again. Despite this major change in protocol, the entry for the Itolizumab trial on the CTRI database continues to suggest incorrectly that the randomised trial included 30 patients.

During the July 13 press conference, Athalye repeated that 30 patients had been randomised. When asked why CTRI hadn’t been updated, Athalye said, “Because the space is limited (on CTRI), you cannot explain all this.”

Pramesh said such a change in protocol made little sense, and raised questions about whether the Biocon trial could even be called a randomised one. “I wouldn’t call it a randomised controlled trial if five patients were not randomised, and yet the analysis of efficacy included these five patients.”

Dropping patients

Another major shortcoming of the trial, which wasn’t shared in the press conference, was that even though at least two patients had dropped out from the control arm after randomisation and after receiving their first dose[footnote]Apart from the five whom investigators set aside to monitor for adverse effects after randomisation [/footnote], the investigators didn’t include these patients during their analysis of whether Itolizumab was more effective than the standard of care.

According to the second contradictory presentation on Biocon’s website, these patients suffered infusion reactions – in which the drug triggers symptoms like fever and chills. One of them dropped out and recovered, while the other dropped out but went on to die from COVID-19 complications nine days later, the company noted.

Given that the trial’s primary endpoint was mortality at 30 days, the investigators should ideally have included the status of these two patients while analysing the drug’s efficacy. Instead, according to the second presentation, the investigators replaced these two patients with two others in the trial, and conducted their analysis.

Also read: Itolizumab for COVID-19: Who Benefits When the Drug Regulator Is Opaque?

Experts said this practice of excluding patients who drop out – called a per-protocol analysis – could make the drug seem better than it is. Because those who drop out often do so because of adverse effects from the drug, tracking every single person who was initially randomised is important to get a realistic picture of the drug’s true impact – a type of analysis called ‘intention to treat’.

“The thing to do is that, even if the patient doesn’t get the drug, you analyse them as long as they were randomised. Otherwise it is so easy for researchers to fudge data,” Pramesh said. “You wait for patients to be randomised: if the patient is high risk, you replace them with a low risk patient, and you go on with it until you get whatever result you want. This is why we insist that any randomised trial must be analysed on an intention-to-treat basis.”

In Biocon’s case, Athalye’s slides at the press conference suggest the company first recruited and randomised 32 patients. Next, two patients seemingly dropped out for unknown reasons. Then, two more patients in the Itolizumab arm apparently dropped out due to infusion reactions but were replaced. This left 30 patients, whose details were eventually analysed.

Such per-protocol analysis is completely unsuited for the type of trial Biocon was trying to conduct, Pramesh said.

Primary endpoints added half way

Several experts also criticised Biocon for its decision to add five primary endpoints halfway through the trial. A primary endpoint – such as mortality at 30 days, which Biocon initially chose – is the main clinical outcome that a trial is designed to measure. If a drug fails to make a difference on this endpoint, scientists consider the drug to have failed in the trial.

Most phase 1 and 2 trials, which are relatively smaller, have one or at most two primary endpoints, several experts told The Wire Science. There are good reasons for this. When the number of primary endpoints goes up, the chances of ‘winning’, or meeting at least one of these endpoints, even if the drug itself isn’t effective also goes up. To account for the greater probability of false-positive results due to multiple endpoints, Pramesh said, researchers ought to adjust the trial design by expanding the cohort size with each extra endpoint.

Adjustments or not, using multiple endpoints in small trials is a bad idea because doing so allows investigators greater room to cheat. Multiple endpoints “are, of course, another trick to dilute the primacy of the endpoint such that one or other of the chosen endpoints will show a difference, and then this one improvement can be touted as evidence of effectiveness,” Rao said.

This is why the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance for clinical trials suggests several best practices. First, primary endpoints must be defined before the trial begins. This prevents researchers from the equivalent of painting a target after throwing the dart, or creating new endpoints after seeing the data. This practice is called data dredging or p-hacking. Second, when multiple endpoints are added, they must be adjusted for.

But the Biocon trial investigators added five new endpoints midway. While they specified “mortality at 30 days” as the primary endpoint at the start, on August 18, more than a month after the trial had concluded, five new endpoints appeared on the CTRI’s website. These included the proportion of patients with deterioration of lung function and a reduction in the fraction of patients who needed non-invasive ventilation. The sample size hasn’t changed, however.

Athalye said the endpoints had actually been altered sometime around the end of May (midway through the trial) but that CTRI didn’t allow investigators to upload the updates right away.

He provided two reasons for the decision to add several new endpoints. First, he said, the investigators had thought at the beginning of the trial that mortality was the best endpoint, and that the FDA had recommended the same thing in their guidance for COVID-9 trials as well.

However, he added, the investigators had been concerned that the primary endpoint of mortality may not be met in such a small trial. And if patients improved on other parameters – like the need for invasive ventilation – the mortality endpoint could miss this.

“When you start a trial, you don’t know how it will end up. If there were no deaths in both arms, and if patients in control arms had not died, but were getting sicker and on ventilators, while the other patients had actually improved and been weaned off (ventilators) – how would you capture that?”

Subsequently, according to him, the FDA had updated its guidance with other relevant endpoints for COVID-19 trials, because of which the company decided to add them as well.

But other scientists say that while there could be legitimate reasons to alter endpoints as new information changes how we think of COVID-19, adding five new endpoints is unheard of.

“For a disease like COVID-19, you are learning something new every day. So you could learn about a more relevant new endpoint – I am not discounting that,” Pramesh said. “But then you would change the primary endpoint, [and] not add five more and come up with six. That’s terrible science. It sounds like a fishing expedition.”

Such an exercise may have passed muster in a much larger trial, said Somashekhar Nimbalkar, the head of the department of paediatrics at Pramukhswami Medical College, Gujarat. But “with 30 patients, having six primary outcomes is ludicrous.”

How did investigators calculate sample size?

The small size of the Itolizumab trial has been a point of contention since the company first announced its results. However, the company still hasn’t been able to clarify why it kept the trial so small, given that it was shooting for regulatory approval.

Several other drugs that have been approved for use against COVID-19, such as remdesivir and dexamethasone, have randomised hundreds of patients. This is because scientists calculate the size of the trial based on the minimum expected effectiveness of the drug, which is also useful to patients, according to Rao.

Rao emphasised the ‘minimum’ here: scientists must calculate the sample size not based on the desired effectiveness of the drug but the minimum level of effectiveness that is useful to patients. Doing this ensures that any drug that crosses this threshold isn’t rejected. Using an arbitrarily high bar, on the other hand, risks the abandonment of drugs that have potential.

When The Wire Science asked Athalye how Biocon researchers had determined the sample size for the Itolizumab trial, Athalye said the company had assumed that the background mortality in the control arm would be 40%, while Itolizumab would bring about a 50% reduction in mortality to 20% in the drug arm.

There are several problems with this logic. First, epidemiologists and statisticians contacted by The Wire Science said that according to these assumptions, to have an 80% chance of capturing the drug’s true effect given a cohort size and a less than 5% chance of capturing a false effect, the trial would have needed – at the very least – over a hundred patients.

Second, both Rao and Pramesh said that a 50% reduction in mortality seemed an irrational assumption for the Itolizumab trial investigators – unless they were okay with rejecting any drug that was even slightly less efficacious.

“With COVID-19, if you are able to reduce mortality by even 25-33%, that’s a serious clinical improvement,” Pramesh said. Choosing a sample size assuming a mortality reduction as high as 50% would mean the company would have rejected a drug that showed even a 25% improvement.

“The effectiveness has to be based on current, real-world experience of treating patients of the kind who fit your inclusion criteria,” Rao said. “I don’t accept that it is as high as 50%.”

Athalye contested this, saying some trial designs, including the Simon two-stage, allow sizes as small as 30. “Typically, a sample size of 30 is empirically chosen for products being developed for orphan indications,” he said.[footnote]An orphan indication is a disease that doesn’t have any treatment [/footnote] “For rare diseases, or wherever there is an emergency, you have different statistics based on a staggered approach.”

He added that the plan was to expand the trial to recruit more patients if there hadn’t been a statistically significant difference in mortality in both arms.

Again, this description of a Simon two-stage trial is at odds with how other scientists define it. According to Pramesh, a Simon two-stage is a single-arm trial designed to prevent ineffective drugs from progressing to phase III. Before commencing the first stage, researchers decide that if a certain number of patients respond to the drug, they will move to the trial’s second stage. If fewer than that number respond, the trial is suspended.

That is, a Simon two-stage allows stopping for futility but not stopping for efficacy.

However, Biocon claimed that they had stopped the trial for efficacy – i.e. because they had been able to demonstrate the drug’s efficacy in the first stage.

The CTRI entry for the Biocon trial makes no mention of the two-stage design.

What next?

Athalye’s words at the press conference and the second presentation are inconsistent in many other ways. For example, a table shared by Athalye indicated that there were very few patients with comorbidities, like diabetes, in the control arm – but the second presentation showed that even the control arm had several of them.

The presentation also showed that a patient in the control arm had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a detail missing from Athalye’s presentation.

As a result, scientists are calling for Biocon to release more details, including how patients were randomised.

But even if these details are released, experts said such a small trial shouldn’t have convinced the CDSCO to approve the drug. “You really can’t draw the conclusion that the company wants to draw based on these numbers. Unless they conduct a far bigger trial with better trial-monitoring and reporting procedures, I can’t see them getting a license in Europe or America,” Rao said.

Athalye said the paper describing the trial and its results was still undergoing peer review, and will be published after that.

Priyanka Pulla is a science writer.

The reporting for this article was supported by a grant from the Thakur Family Foundation. The foundation did not exercise any editorial control over the contents of the article.