In a two-storied building, past twinkling glass facades of software makers, Akhilesh Kumar was buried in a relatively low-tech activity. He was rhythmically hammering a quartzite stone block with hard and soft blows.

It’s a ritual he settles down to everyday at his workspace in Chennai. This stone-tool-making experiment is his key to unraveling stories about prehistoric humans in India.

“You must understand how these tools were actually made, and without experiments you can get stuck at some point of time,” said archaeologist Shanti Pappu, Kumar’s collaborator.

Over two decades, the two have suffered a merciless sun and hissing reptiles as they shovelled for stone tools, or lithics, in Attirampakkam. ‘Lithic’ comes from the Greek word for stone, lithos.

Also read: An Indian Fossil Hunter’s Chase for Dinosaur Relics

Attirampakkam is located along a meandering river northwest of Chennai, and is a national treasure of sorts. Some of India’s first prehistoric stone tools were discovered here over 150 years ago.

In India, archaeologists rarely come across skulls and bones of ancient humans because a clammy environment catalyses their decomposition. However, stones are resilient to this assault, helping us chase the trails of human evolution and migration.

When Pappu and Kumar decided to explore Attirampakkam in 1999, they hired labourers to shovel pits deep enough to gobble a bus. As sand and gravel were scooped out, they discovered a layer cake of lower palaeolithic, or old-stone-age, tools as well as inscrutable rock shards.

Pappu and Kumar had learnt to make stone implements through a course in France. In 2008, they put it into practice to label unidentifiable stone chips found at the site. They grabbed some hammerstones shaped like tennis balls and started sculpting stone tools to mimic those found on site.

This act is called knapping, and it’s fast becoming an important tool for scientists trying to trace human evolution.

§

Modern humans have evolved through several changes from tree-borne, ape-like ancestors who existed in Africa six million years ago. A majority of anthropologists recognise around a dozen species of early humans that increasingly walked upright as they climbed down trees in search of food. The most adventurous among them was the species Homo erectus.

These tool-making ancestors of ours, with bodies similar to modern humans, appeared in Africa more than 1.8 million years ago. They were the first archaic humans to leave the continent.

On the geological timescale, this was in the Pleistocene epoch, the start of the last known ice age on Earth. Oceans swelled into glaciers. Woolly mammoths, giant deer and sloths wandered the planet.

It was in this epoch that Homo erectus began their global migrations, travelling to India from Africa through parts of West Asia in small bands.

They hiked from India’s north to its south, along the country’s western coast before swerving to the east and reaching sites like Attirampakkam. For the past decade, Kumar has focused on mimicking the artisanship of the Attirampakkam settlers.

The experiments helped glue together multiple events. For instance, it struck Kumar and Pappu that it required early humans a group effort to break a big rock into smaller a piece that could be sculpted by hand.

“You learn that it requires lots and lots of planning,” said Kumar.

§

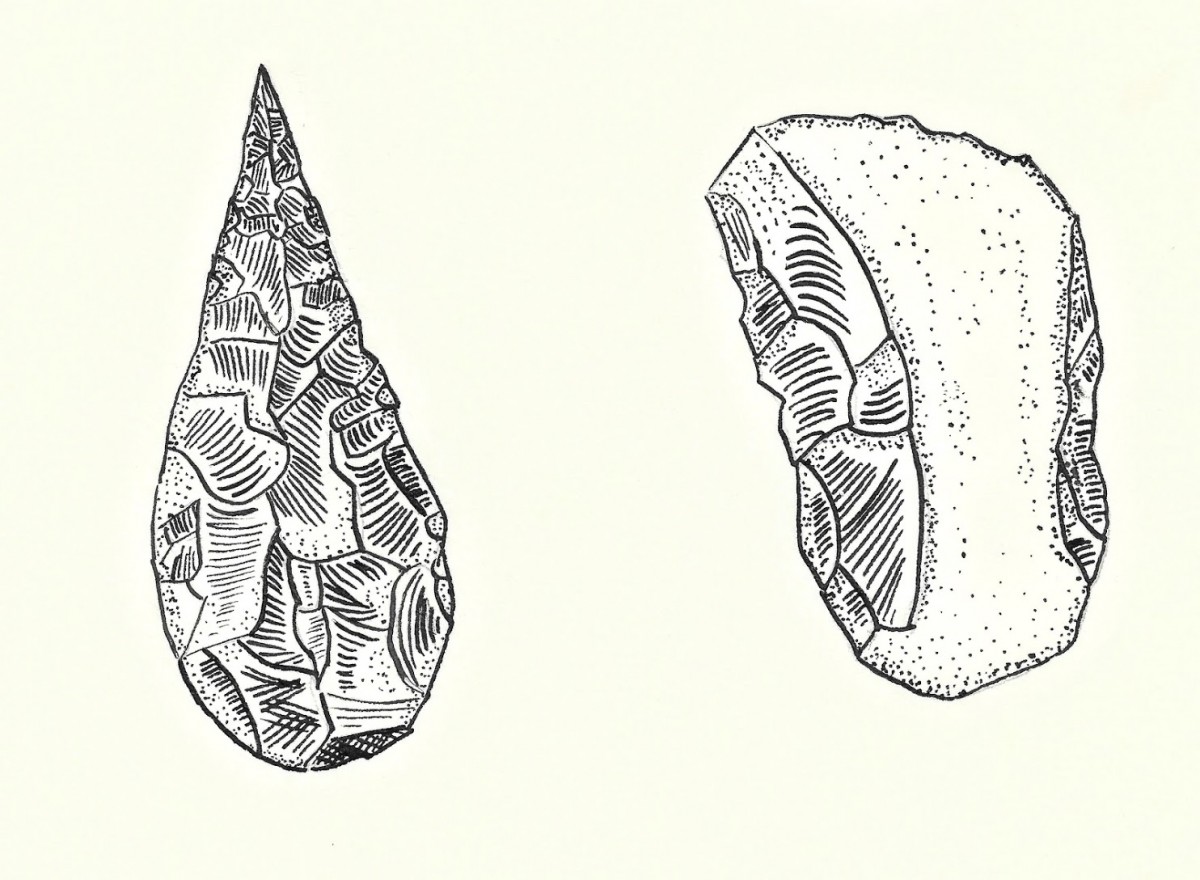

Kumar often toils eight to nine hours a day chiseling stone tools. Cuts and calluses dot his palm. Pappu stressed that for experimental knappers, it is almost an obsession. Once, Kumar worked a whole day chiseling six hand axes – palm-sized stone tool shaped like tear drops.

In the early history of man, the hand axe was stone-tool tech 2.0.

”These are beautifully made tools, probably better made than they have to be,” said Nicholas Toth, speaking about hand axes found around the world.

Toth and his spouse Kathy Schick are veteran archaeologists who run the US-based Stone Age Institute, which focuses on the study and practice of primitive technologies.

“Some people think that hand axes are kind of the Swiss Army knives of prehistory, that they have many different functions,” added Toth.

Also read: Tamil Nadu’s Chembarambakkam Lake Foretells an Aridity in the Sands of Time

The hand axe could bludgeon, crush and scrape. As a result, archaic man’s lunch options expanded. Now, he could strategise with his band to trap and club an animal, and then butcher it. The group could then sink their teeth into the choicest organs like the liver and the brain.

Over time, as food was chopped using stone tools and cooked over fire, digestion got simpler and our ancestors’ guts shrank. This freed energy for an expanding brain.

As Schick put it, “It is interesting that only after the advent of stone tools in human prehistory that we start seeing the dramatic growth in the size of the brain.”

The oldest hand axes found in Africa go as far back as 1.7 million years, and are often are found alongside fossils of Homo erectus, the hunter-gatherers. They were taller, had smaller jaws and bones, and a bigger brain than their predecessors, and were anatomically closer to the modern human. They also worked with fire.

Our brains are thrice as big as those of our earliest tool-making ancestors. The jump in cognitive capacity was accompanied by a rising sophistication in stone tools and increased miniaturisation – a bit like the lighter laptops and slimmer phones of today.

§

Until Kumar and Pappu scrutinised the stone tools at Attirampakkam, scientists had assumed that early humans existed in India some 600,000 years ago.

But the duo’s research revealed something else. Once they started crafting stone tools, they had to reclassify nearly 10,000 finds. The orphaned shards found in Attirampakkam were matched to the waste chips falling off the tools that Kumar was making. This unveiled artefacts missing from the site. This is akin to guessing what a person had eaten based on crumbs dropped on the table.

Then around 2011, chemical analysis that reveals the duration for which tools had been buried without exposure to light revealed that Homo erectus had migrated to India from east Africa not 600,000 years ago but more than a million years ago.

Tool-making experiments have shown that all the settlers in Attirampakkam were expert knappers, a badge now worn by Kumar as well.

“I make hand-axes, cleavers. You can see the blades and microliths,” Kumar said. “So I could have been at ease in any lithic-technology age.”

The writer is an independent podcaster and publishes audio documentaries focusing on deep history via desistonesandbones.org.