A view of Osmania General Hospital, Hyderabad, December 2007. Photo: fraboof/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Bengaluru: Junior doctors in the Osmania General Hospital, Hyderabad, have alleged that since April, hundreds of people have died due to suspected COVID-19 at the hospital and that those deaths haven’t been captured in Telangana’s official COVID-19 death toll.

Satya*, a graduate from the Osmania Medical College’s master of surgery programme, told The Wire Science that several patients with COVID-19 symptoms died without being tested, but their medical certificates of cause of death (MCCDs) didn’t mention suspicion of COVID-19 as a cause – contrary to Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR) guidelines. Satya served in the hospital’s surgical emergency ward until recently.

“The underreporting is institutionalised at multiple levels: first, you have under-testing, then you have underreporting of deaths that are tested,” Satya said. “These are being recorded by the hospital but they are not reflected in the state’s daily bulletin.”

Two other junior doctors currently serving at the hospital – a tertiary care facility with 1,168 beds – echoed Satya’s claims but didn’t wish to be named. A postgraduate student in the college’s medicine programme, who has served in one of the hospital’s several wards catering to patients of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI), said even deaths of patients who were highly likely to be suffering from COVID-19 were often not recorded as COVID-19 deaths if the test results weren’t available on time.

For example, several deaths for which computed tomography (CT) scans showed multiple signs of COVID-19 hadn’t been recorded as COVID-19 deaths. One reason was that the students staffing the wards had received no guidelines on how to certify COVID-19 deaths.

Dying too fast to be tested

Such underreporting has happened in two ways over the last few months, the postgraduate student said. First, if a patient with COVID-19 symptoms tested ‘negative’ with the RT-PCR test, her death wouldn’t be counted as such. Second, if the RT-PCR test result hadn’t arrived by the time the patient died, her death was again likely to be missed in the state’s COVID-19 deaths tally.

The student said the second scenario is not unusual because patients frequently died within hours of being admitted to the hospital, leaving little time for test samples to be collected. “We have limitations in sample collection and processing. So technicians collect in three shifts in a day – early morning, afternoon, evening,” the student said. “If a [patient] comes at 9 am in the morning and dies before the sample is collected, [the patient’s case] is considered a non-COVID-19-case.”

According to guidelines from the National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research (an ICMR body), if a patient shows COVID-19 symptoms but tests negative for the novel coronavirus or can’t be tested, her death must be considered to be a ‘suspected COVID-19 death’ on the MCCD. These guidelines ensure false negatives on an RT-PCR test – when a test comes back ‘negative’ even though the person is actually infected – don’t falsely suppress death numbers. They’re also meant to keep low rates of testing from distorting the death toll.

Telangana has braved more than its fair share of controversies over testing the bodies of patients who have died. The state’s director of medical education, Ramesh Reddy, wrote a letter in April to hospital medical superintendents admonishing them for testing dead bodies for the virus. Subsequently, on May 26, the Telangana high court reprimanded the state for trying to hide COVID-19 deaths and ordered the government to test all dead bodies.

Then, on June 17, the Supreme Court stayed the high court’s order after the state government challenged it. As a result, the bodies of deceased patients who had shown symptoms of COVID-19 continue to go untested, the students at Osmania Hospital said.

Satya said that while the hospital was testing more suspected patients now, it had been extremely hard for doctors to order a test until two months ago. Initially, any doctor who wished to ask for a test had to request the duty medical officer of the medicine department, creating a significant bottleneck. This situation improved later: tests can now be ordered with the approval of an assistant professor in any department, Satya said. However, he added, the “threshold for testing” remains high, and several patients continue to slip through the cracks.

Spike in SARI cases

Osmania General Hospital has witnessed a clear spike in the number of SARI patients relative to this time last year. However, only a small fraction of deaths among these patients have been attributed to COVID-19, the students said.

Until 2020, the hospital had treated very few SARI patients because these patients typically go to the Government General and Chest Hospital, Sravan Kumar, who heads the department of medicine at Osmania Hospital, said. Once the COVID-19 outbreak began, the hospital admitted many SARI cases; of them, those who tested positive for COVID-19 were sent to the Gandhi Hospital, which is designated to treat such patients.

However, it soon became clear that some SARI cases were so critically ill that they’d have to be stabilised before being moved to Gandhi Hospital. As a result, Osmania set up its own isolation wards for SARI patients. On August 1, the hospital had 10 SARI wards capable of accommodating up to 100 patients. Hospital officials said this capacity is set to rise since cases continue to increase as well.

According to one postgraduate student The Wire Science spoke to, within these 10 SARI wards, the hospital had 29 SARI deaths in April, 97 deaths in May, 268 in June and 256 from July 1 until 17. “SARI deaths did occur (last year). But it was generally 1-2 deaths a day, so not more than 40-50 SARI deaths a month,” the student said.

Meanwhile, the entire state of Telangana had reported only 28 cumulative COVID-19 deaths by April 30; 82 by May 31; 260 by June 30; and 519 by July 31.

About the allegations of a large number of SARI deaths being underreported, the hospital’s medical superintendent Pandu Naik said the hospital didn’t maintain a record of SARI deaths, and that he could neither confirm nor deny the numbers.

He did confirm that in cases where the test result was unavailable or was ‘negative’, the hospital didn’t report the death as being due to COVID-19 to the state. He also admitted some patients did die without being tested. “Patients are coming with severe distress, and dying within 1-2 hours.” Then again, he clarified, fewer deaths fall in this category than the students had claimed.

Naik also said the hospital had reported two COVID-19 deaths in March, four in April, four in May and 61 in June. He agreed the hospital had noticed a spike in SARI cases compared to 2019 but said it was difficult to say what the causes of the non-COVID-19 deaths could be. “Many of the patients with SARI are dying due to chronic cardiac, renal and lung problems,” he said.

However, ICMR guidelines say such chronic comorbidities can’t be considered to be the direct cause of death.

Suspected deaths in other wards not recorded

SARI wards aren’t the only place where suspected COVID-19 deaths are happening. A postgraduate student of surgery told The Wire Science that several suspected deaths have been reported from other wards, including the hospital’s surgery and casualty wards.

For example, when a patient requiring emergency surgery is admitted to the surgical ward, she may show either well-known COVID-19 respiratory symptoms like pneumonia or less common signs like mesenteric ischaemia, where the blood supply to the small intestine is disrupted due to a clot in an artery. The student said doctors had seen both presentations on multiple occasions – but without adequate testing, they hadn’t been able to confirm the illness. And if the patient died, it wasn’t reported as a ‘suspected COVID-19 death’.

“We had an absurdly high number of surgical emergency cases [with] incidental lung findings suggestive of COVID-19. But many of them have tested negative,” the student said.

Satya recalled the events surrounding the death of a patient suspected to have COVID-19, whom he had attended to in an unofficial capacity. The patient was a man in his mid-40s, and had a history of fever, cough and difficulty breathing. The family also revealed that the patient’s father had died two days ago at home, of an illness marked by fever and breathlessness, although no doctor had attended to him.

On June 29 afternoon, when the son himself became severely breathless, his family rushed him to Osmania. A friend of Satya’s, who also knew the patient’s family, asked Satya if he could help. So Satya, who had been discharged from duties at the hospital to take his final year exams by then, visited the casualty ward to help the family.

The ward was crowded; no doctor was available to attend to the patient so Satya said he decided to help. A pulse oximeter indicated the patient’s blood had very little oxygen. And he was so breathless that “he was barely able to speak his name,” Satya said. He then ordered an X-ray and found a hazy, whitish film overlying both lobes of the image of the lungs – a sign of COVID-19. “Both lungs were affected severely,” he said.

The family then rushed to fill the paperwork to admit the patient to one of Osmania’s SARI wards, but in the meantime, the patient died in the casualty ward. According to Satya, no one in the casualty ward had ordered a test for COVID-19 in the chaos.

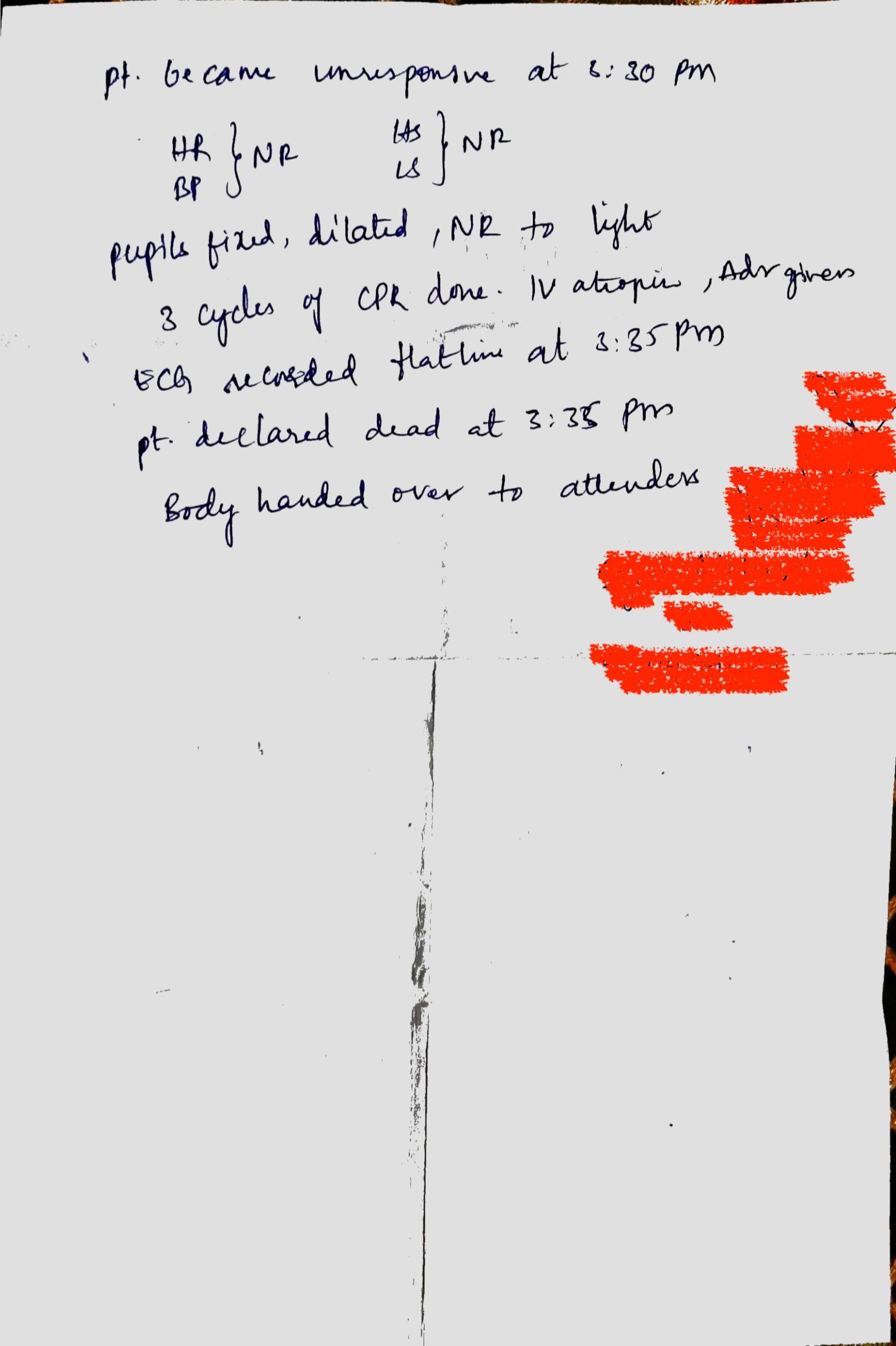

The patient also didn’t receive an MCCD, but only an out-patient ticket (see image below). The doctors in the casualty ward also didn’t inform the family to follow the proper burial protocol. Satya said he counselled the patients as best as he could but “they left with the body, routinely, as if it was any death, and not a COVID-19 death. That seems to be the routine in the casualty ward, because it is staffed by MBBS interns who don’t have much experience.” He also alleged the death hadn’t been reported as a COVID-19 death.

The Wire Science spoke to the casualty medical officer, who oversees the casualty ward, on July 29 to ask why the patient didn’t receive an MCCD. The officer said he hadn’t been on duty the day of the death and couldn’t answer the question.

Naik, the medical superintendent, confirmed that all patients should receive an MCCD but said he didn’t know why this patient did not. However, given the patient had never been tested for the virus, Naik said it was unlikely that his death would’ve been reported as COVID-19 death.

The allegations persist

Allegations of under-reporting have plagued Osmania Hospital as well as many of Telangana’s government hospitals since COVID-19 first broke out. K.U.N. Vishnu, the president of the Telangana Junior Doctors’ Association, told The Wire Science that he and several other doctors had flagged under-testing and fatality underreporting at Osmania Hospital with Naik as well as the state’s director of medical education, Ramesh Reddy. But Reddy didn’t “respond positively,” Vishnu said.

Apart from suspected deaths, Telangana also doesn’t seem to be reporting all deaths among patients who had been confirmed to have COVID-19 using RT-PCR tests. On May 16, Telangana’s health minister Eatala Rajender said at a press conference that even among patients who had tested positive, deaths wouldn’t be attributed to COVID-19 if they were determined to be due to comorbidities. He also claimed this practice comes recommended by the ICMR guidelines — except the guidelines say the opposite.

According to the document, “Patients may present with other pre-existing comorbid conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma, chronic bronchitis, ischaemic heart disease, cancer and diabetes mellitus. These conditions increase the risk of developing respiratory infections, and may lead to complications and severe disease in a COVID-19 positive individual. These conditions are not considered as [underlying causes of death] as they have not directly not caused death due to COVID-19.”

Putting this together with the minister’s interpretation could mean the state’s death toll is almost double of what it has been publishing. For instance, the state government’s media bulletin on July 31 claimed the state had had 519 deaths until then – but that 53.87% of the deaths were due to comorbidities. This could mean the state’s actual toll was 963 deaths until then, an interpretation The Hindu first reported on July 28.

The Wire Science repeatedly contacted Telangana’s director of public health, G. Srinivasa Rao, and Reddy, over email, WhatsApp and phone calls to confirm if this reading was correct. Neither Rao nor Reddy had responded at the time of publication.

* Name changed to protect identity.

Priyanka Pulla is a science writer.

The reporting for this article was supported by a grant from the Thakur Family Foundation. The foundation did not exercise any editorial control over the contents of the article.